While gospel music can be traced back to the early 17th century, black gospel music really took shape in the late 18th century, when slaves began converting to Christianity and proclaiming their faith through work music.

Many timeless spirituals emerged from the American South in the years to follow.

Black voices were subsequently raised in praise, finding solace in the stories they read and sang from the Bible. They were songs that spoke of the hardships African Americans had endured and the newfound freedom they won by praising God for helping them rid themselves of their shackles and leading them to a life of faith through worship and honoring their cultural heritage.

Elements of West African music infused the songs the slaves sang in the fields. With the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and the end of the Civil War and the 13th Amendment in 1865, the songs took on a newfound meaning praising the Lord for the freedom they had yearned for.

The 1867 book “Slave Songs of the United States” included the gospel spirituals “Roll Jordan Roll,” “Jacob’s Ladder,” and “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.” The songs spoke of the suffering they endured and the faith in God that allowed them to survive, with the hope of the life they would find in heaven.

RELATED: How Harry Belafonte and Irving Burgie Helped Popularize Caribbean Calypso Music

In 1871, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were formed. They were an a cappella group from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. They performed African American spirituals sung by slaves prior to the Civil War. Fisk University was the first American university to offer liberal arts courses to African Americans, helping to break racial barriers during the latter part of the 19th century.

Among the songs they would sing were “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Go Down Moses.” The group, which has won numerous awards and honors and is a member of the Gospel Music Hall of Fame, still performs today.

Many of these songs also found their way into black Catholic churches, which provided a safe haven where parishioners’ voices could join in unison singing the spirituals that incorporated their traditions with biblical themes.

The early 20th century brought a new awareness of black gospel music when singer and songwriter Thomas A. Dorsey, the son of a Baptist minister from Georgia, traded his secular career for a life devoted to Christian music. Known as the “Father of Gospel,” Dorsey’s catalog of songs includes “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” famously recorded by Elvis Presley, as well as “Peace in the Valley” by Johnny Cash.

Around the same time, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a Pentecostal, also influenced artists such as Presley, Cash, Tina Turner, Little Richard, and Jerry Lee Lewis. They all recorded the Arkansas-born Tharpe’s songs.

In the 1930s, the black gospel quartet Blind Boys of Alabama emerged. The six-time Grammy award-winning group is still performing and recording songs like “Amazing Grace,” “Free at Last,” and “I Shall Not Walk Alone.”

Catholic convert Sister Thea Bowman, the granddaughter of slaves, was one of the most important voices of Christian music during the 20th century, recording songs like “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “Oh Mary, Don’t You Weep for Me,” “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” and “Go Tell it On the Mountain.”

Sister Thea, a Franciscan nun, was an integral figure in bringing African American spirituals to the Church and famously led the nation’s bishops in singing “We Shall Overcome” at the 1989 U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops annual gathering in South Orange, New Jersey.

“The interesting thing about it is Catholic evangelization developed in the United States alongside the growth of what we consider to be gospel music,” said Joseph Murray, co-music director at St. Martin de Porres Parish in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

RELATED: Keys to the Past: How Brooklyn Church’s Pipe Organ Bridges Faith, History

During the 1940s and 1950s, popular black Catholic artists like jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong began recording black gospel music.

Armstrong’s rendition of “When the Saints Go Marching In” remains one of his most popular recordings. Nina Simone also recorded an entire gospel album titled “The Gospel According to Nina Simone.”

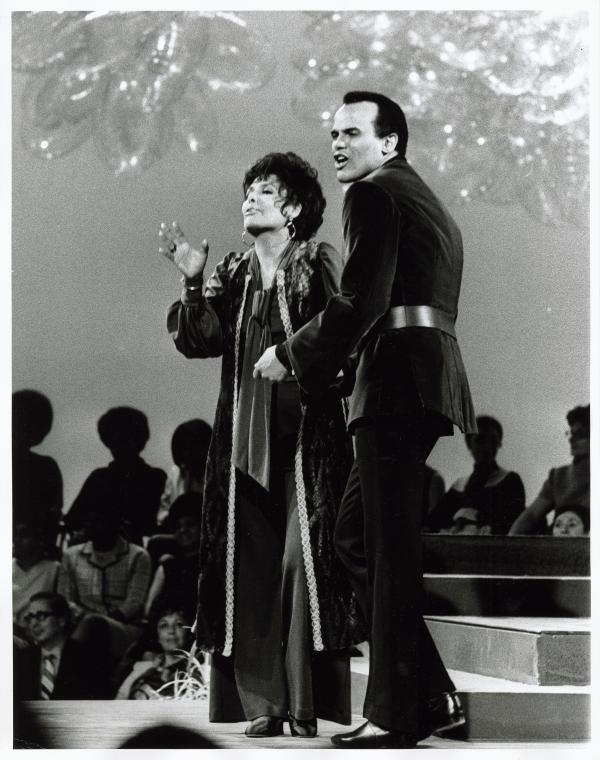

Meanwhile, Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne helped usher in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s with songs like “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

Father Clarence Rivers, a nationally known musician, also played an essential role in the black gospel music movement. He gained popularity during the Civil Rights Movement, combining Gregorian Chant with popular African American spirituals.

Murray noted, however, that enculturation within the Church doesn’t happen until the Second Vatican Council, when gospel music is permitted, and “Pope Paul VI said that this was an essential component of our faith.”

In 1987, “Lead Me, Guide Me,” the first hymnal explicitly compiled for the use of black Catholics, was published. It features traditional spirituals, contemporary black gospel music, and other Catholic hymns.

“The publication of this hymnal made it undeniable that there was a need for a book that speaks directly to the African American Catholic experience, which in and of itself was pulling from all different sources including new material by black Catholic composers of the time, old Negro spirituals, gospel hits that were then transposed and transcribed to make sense in liturgy,” Murray said.

“Lead Me, Guide Me” is still used today.