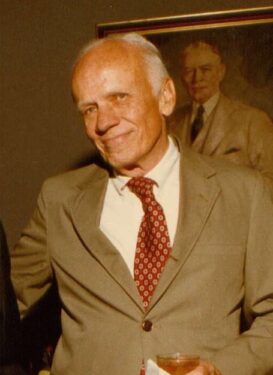

Amid the pandemic, I had a refreshing and renewing experience reading the Catholic existentialist novelist Walker Percy (1916-1990). I was looking through my bookcase trying to find something to read and I spotted Walker Percy’s “Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book” (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983, pp. 262) which I had read many years ago but that I suspected deserved a second look. I was right. Refreshing my memory and challenging me to reflect deeply on Percy’s wonderful insights, the book reminded me of what a prophet he was.

My first contact with Walker Percy was back in the 1950s. I read an essay by him in Commonweal. His name was easy to recall because I had never heard of anyone whose first name was Walker. When I learned that he started writing novels, I immediately read each of the six as they appeared. I wrote about him in the Catholic press and delivered a scholarly paper on his thought for the American Catholic Philosophical Conference. We also exchanged letters. He had agreed to write a comment for the cover of a book I had written about Ingmar Bergman.

When Walker died, I felt as though I had lost a friend. Within two or three days after his death, after offering a Mass for him, I decided to write a book about him which I titled “Walker Percy: Prophetic, Existentialist, Catholic Storyteller” (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 1996, pp. 127).

I chose the title for my book carefully. I believed that Percy was a prophet trying to help his contemporaries either to discover or to recall the most important truths about the human being. While recuperating from tuberculosis, Percy read all the well known existentialist philosophers and was deeply influenced by them, especially by Soren Kierkegaard and Gabriel Marcel. I included the word “storyteller” in my title because, like Percy, I had come to believe that stories can be a marvelous way of communicating both philosophical and religious truths. Dr. Robert Coles, who had written a book about Percy, was kind enough to write the Introduction. In the Introduction, Dr. Coles wrote this excellent summary statement about Walker:

“He was forever taking the pulse of mid-and-late twentieth-century America, trying to figure out what makes us the people we are — our assumptions, worries, hopes, expectations, and he was forever measuring what he heard by the moral and spiritual yardstick of the Catholic Church, whose principles and values and teaching he took seriously, indeed. He knew, of course, that an artist is one who hints, suggests rather than pronounces, hands down rules and mandates, hence the wonderfully comic, yet knowing spirit that informs his fiction — which, at the same time, is full of moral alarm and spiritual energy. His characters make us laugh, entertain us, surprise us, but also bring us up short, bring us to our senses — ‘here’ is what is going on, and ‘there’ is where we seem headed, and so, our jeopardy, our challenge.”

Coles’ statement may be one of the best summaries of Percy’s work.

What I discovered, or perhaps rediscovered, in re-reading “Lost in the Cosmos” was that Percy dealt succinctly, and often humorously, with subjects that I have been stressing in philosophy classes for many years. One subject is scientism. I stress with the students that scientism is not the same as science. A person cannot be educated and be opposed to science. However, scientism is another matter. It is a philosophy that insists that only statements of positive, empirical science, for example, statements of physics, chemistry, and biology are meaningful. All other statements are meaningless. So any statements about God or morality are meaningless because they cannot be checked by some positive or empirical science.

What those who embrace scientism, apparently do not see is that scientism contradicts itself. The statement of scientism, namely that only statements of positive or empirical science are meaningful is not itself a statement of positive or empirical science and so by its principles that statement of scientism is meaningless. In philosophy classes at St. John’s University it takes about thirty seconds to show that scientism contradicts itself but that does not mean that thousands of our contemporaries, who may never have heard the word “scientism” basically think that science is the only way to know.

Besides scientism, another subject, perhaps the subject that Percy deals with more than any other is the mystery of the human person. In his six novels and his books of essays, Percy focuses on what it means to be a human person, what it means to be an image of God. Right now I cannot think of a more important topic.

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, every Tuesday at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.