by Francis X. Rocca

BEIRUT (CNS) – When Pope Benedict XVI stepped off the plane in Beirut Sept. 14, he said he had come to Lebanon, and to the Middle East in general, as a “pilgrim of peace.” In five major talks over the next three days, the pope repeatedly called for peace and underscored the role of Christians in promoting it. Yet his most eloquent message of hope to the troubled region lay not in the diplomatic language of his public statements but in his very presence and the response it evoked from his hosts.

Throughout his trip, Pope Benedict limited himself to general statements of principle on the most contentious political issues, and he avoided some topics altogether.

His insistence that religious freedom is a basic human right and a prerequisite for social harmony was a bold statement in the context of a region where most countries restrict and even prohibit the practice of any faith besides Islam. But like the document he came to Lebanon to present, a collection of his reflections on the 2010 special Synod of Bishops dedicated to Christians in the Middle East, the pope said nothing specific about where and how the region’s Christians are regularly deprived of that right.

The pope twice deplored the human cost of the civil war in neighboring Syria, but his only practical recommendation for an end to the fighting there was a neutral call to end the importation of military arms, which he called a “grave sin.” With regard to religiously inspired violence, the pope made a single generic reference to terrorism and a possible allusion to the subject in the statement that “authentic faith does not lead to death.”

Pope Benedict said nothing at all about the incendiary subject that dominated news coverage in the run-up to his trip: an American-made anti-Islamic film that had inspired often-violent protests in at least a dozen Muslim countries, including Lebanon.

Awareness of that furor no doubt heightened the caution with which the pope treated the most volatile topics during his trip. Ironically, the crisis may also have helped him to get his message across.

With turmoil over the movie spreading across the Middle East, the papal visit suddenly became a much more dramatic and thus more appealing story to the secular press, which probably gave it more coverage as a result, observed Msgr. John E. Kozar, president of the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, who attended the papal events.

For the Lebanese, the pope’s willingness to travel in spite of security concerns — he told reporters on the plane from Rome that he had not considered canceling the trip and that no one had advised him to do so — powerfully underscored his commitment to the country and the region.

Christians Are Not Forgotten

“The mere fact that the Holy Father came at this difficult moment is an indication that Christians here are not forgotten,” said Habib Malik, a professor of history at Lebanese American University.

The pope’s visit served as a showcase for Lebanon, which for years was a model of peaceful coexistence and religious freedom in the Middle East. The show of enthusiasm across sectarian and political lines, in a nation still recovering from the 1975-90 civil war, was a dramatic statement of unity to the outside world and to the Lebanese themselves.

Epitomizing the welcome by Muslim leaders, Lebanon’s grand mufti gave Pope Benedict a written message stating that “any attack on any Christian citizen is an attack on Islam.” And as Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper reported Sept. 17, Lebanese President Michel Suleiman cited the unanimity among political factions over the weekend in arguing that the “way to capitalize on the pope’s visit is via dialogue.”

Pope Benedict would no doubt agree, while limiting his short-term expectations. As he told the president in his arrival speech, Lebanese society’s “equilibrium, which is presented everywhere as an example, is extremely delicate. Sometimes it seems about to snap like a bow which is overstretched or submitted to pressures which are too often partisan, even selfish, contrary and extraneous to Lebanese harmony and gentleness.”

What precisely those pressures might be, the pope prudently declined to say.

The pope acknowledged the suffering of Christians in the Middle East, reassuring them and urging them to promote peace through religiously inspired service to their societies.

“Your sufferings are not in vain,” the pope told a crowd of at least 350,000 at a sweltering outdoor Mass at Beirut’s City Center Waterfront Sept. 16. “Remain ever hopeful because of Christ.”

In his homily, Pope Benedict commented on the day’s reading from the Gospel of St. Mark, in which Jesus foretells His death and resurrection. Jesus is a “Messiah who suffers,” the pope said, “a Messiah who serves, and not some triumphant political savior.”

Speaking in a region riven by sectarian politics, where party loyalties are often determined by religious affiliation, the pope warned that people can invoke Jesus to “advance agendas which are not his, to raise false temporal hopes in his regard.”

Redemptive Suffering

Pope Benedict told his listeners, whose travails of war and economic insecurity he had acknowledged repeatedly throughout his visit, that Christianity is essentially a faith of redemptive suffering.

“Following Jesus means taking up one’s cross and following in his footsteps along a difficult path which leads not to earthly power or glory but, if necessary, to self-abandonment, to losing one’s life for Christ and the Gospel in order to save it,” he said.

Yet Pope Benedict also cited another of the day’s Mass readings, the epistle of St. James, to emphasize the spiritual value of “concrete actions” and works, concluding that “service is a fundamental element” of Christian identity.

Addressing a region where Christian-run social services, including schools and health care facilities, are extensively used by the Muslim majority, the pope stressed the importance of “serving the poor, the outcast and the suffering,” and called on Christians to be “servants of peace and reconciliation in the Middle East.”

“This is an essential testimony which Christians must render here, in cooperation with all people of good will,” Pope Benedict said.

During the homily, the only sound was the pope’s voice and its echo from the loudspeakers. Many people leaned over and bowed their heads with eyes closed, so they could concentrate more deeply.

Following the Mass, the pope formally presented patriarchs and bishops of the Middle East with a document of his reflections on the 2010 special Synod of Bishops, which was dedicated to the region’s Christians. In the 90-page document, called an apostolic exhortation, the pope called for religious freedom and warned of the dangers of fundamentalism.

Sheltered from the sun only by white baseball caps and the occasional umbrella, people had already packed the city’s central district by 8 a.m., almost an hour-and-a-half before the pope arrived in the popemobile, which took him to the foot of the altar. In temperatures that rose into the high 80s, the pope celebrated Mass under a canopy while bishops and patriarchs on either side wiped their brows and fanned themselves with programs.

Aside from the complimentary white pope caps, people in the crowd improvised versions of sun protection with torn pieces of corrugated boxes tied around heads and papal and Lebanese flags worn as bandanas.

George Srour, 38, estimated that 20,000 people came from Zahle in a convoy of chartered school buses, leaving at 5 a.m. for the 10 a.m. Mass.

“We Christians must be united and participate” in the pope’s visit, Srour told Catholic News Service, “otherwise there will be no more Lebanon. It will become like Iraq, and now Syria, with all the Christians leaving.”

On the first day of his visit, Pope Benedict signed a major document calling on Catholics in the Middle East to engage in dialogue with Orthodox, Jewish and Muslim neighbors but also to affirm and defend their right to live freely in the region where Christianity was born.

In a ceremony at the Melkite Catholic Basilica of St. Paul in Harissa Sept. 14, Pope Benedict signed the apostolic exhortation.

Esteem for Islam

A section dedicated to interreligious dialogue encouraged Christians to “esteem” the region’s dominant religion, Islam, lamenting that “both sides have used doctrinal differences as a pretext for justifying, in the name of religion, acts of intolerance, discrimination, marginalization and even of persecution.”

Yet in a reflection of the precarious position of Christians in most of the region today, where they frequently experience negative legal and social discrimination, the pope called for Arab societies to “move beyond tolerance to religious freedom.”

The “pinnacle of all other freedoms,” religious freedom is a “sacred and inalienable right,” which includes the “freedom to choose the religion which one judges to be true and to manifest one’s beliefs in public,” the pope wrote.

It is a civil crime in some Muslim countries for Muslims to convert to another faith and, in Saudi Arabia, Catholic priests have been arrested for celebrating Mass, even in private.

The papal document, called an apostolic exhortation, denounced “religious fundamentalism” as the opposite extreme of the secularization that Pope Benedict has often criticized in the context of contemporary Western society.

Fundamentalism, which “afflicts all religious communities,” thrives on “economic and political instability, a readiness on the part of some to manipulate others, and a defective understanding of religion,” the pope wrote. “It wants to gain power, at times violently, over individual consciences, and over religion itself, for political reasons.”

Many Christians in the Middle East have expressed growing alarm at the rise of Islamist extremism, especially since the so-called Arab Spring democracy movement has toppled or threatened secular regimes that guaranteed religious minorities the freedom to practice their faith.

Earlier in the day, the pope told reporters accompanying him on the plane from Rome that the Arab Spring represented positive aspirations for democracy and liberty and hence a “renewed Arab identity.” But he warned against the danger of forgetting that “human liberty is always a shared reality,” and consequently failing to protect the rights of Christian minorities in Muslim countries.

Denouncing Discrimination Against Women

The apostolic exhortation criticized another aspect of social reality in the Middle East by denouncing the “wide variety of forms of discrimination” against women in the region.

“In recognition of their innate inclination to love and protect human life, and paying tribute to their specific contribution to education, health care, humanitarian work and the apostolic life,” Pope Benedict wrote, “I believe that women should play, and be allowed to play, a greater part in public and ecclesial life.”

In his speech at the document’s signing, Pope Benedict observed that Sept. 14 was the feast of the Exaltation of Holy Cross, a celebration associated with Emperor Constantine the Great, who in the year 313 granted religious freedom in the Roman Empire and was later baptized.

The pope urged Christians in the Middle East to “act concretely … in a way like that of the Emperor Constantine, who could bear witness and bring Christians forth from discrimination to enable them openly and freely to live their faith in Christ crucified, dead and risen for the salvation of all.”

While the pope signed the document in an atmosphere of interreligious harmony, with Orthodox, Muslim and Druze leaders in attendance at the basilica, the same day brought an outburst of religiously inspired violence to Lebanon.

During a protest against the American-made anti-Muslim film that prompted demonstrations in Libya, Egypt and Yemen earlier in the week, a group attempted to storm a Lebanese government building in the northern city of Tripoli. The resulting clashes left one person dead and 25 wounded, local media reported. According to Voice of Lebanon radio, Lebanese army troops were deployed to Tripoli to prevent further violence.

Mohammad Samak, the Muslim secretary-general of Lebanon’s Christian-Muslim Committee for Dialogue, told Catholic News Service that the violence had nothing to do with the pope’s visit.

“All Muslim leaders and Muslim organizations — political and religious — they are all welcoming the Holy Father and welcoming his visit,” Samak said. “I hope his visit will give more credibility to what we have affirmed as the message of Lebanon — a country of conviviality between Christians and Muslims who are living peacefully and in harmony together for hundreds of years now.”

Bishop Joseph Mouawad, vicar of Lebanon’s Maronite Patriarchate, told Catholic News Service that the apostolic exhortation represents “a roadmap for Christians of the Middle East to live their renewal at all levels, especially at the level of communion.”

The exhortation will also be a call to dialogue, he said, especially between Christians and Muslims.

Chaldean Archbishop Louis Sako of Kirkuk, Iraq, said now church leaders in each Middle Eastern country must “work on how to translate the exhortation into real life in our communities and also in our Muslim and Christian relationships.”

The pope also urged young Christians in the Middle East not to flee violence and economic insecurity through emigration but to draw strength from their faith and make peace in their troubled region.

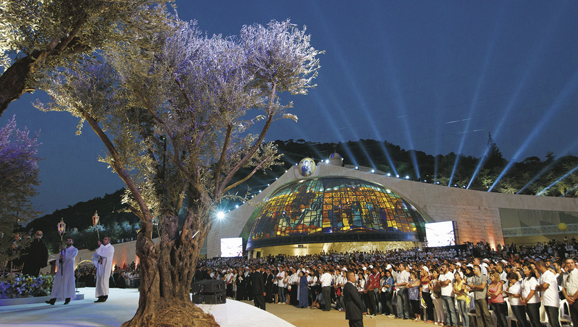

The pope spoke to some 20,000 young people from several Middle Eastern countries gathered outside the residence of the Maronite patriarch in Bkerke in a celebration that included fireworks, spotlights, singing and prayer.

[hr]Contributing to this story was Doreen Abi Raad.