A local elderly Jewish gentleman, who has rubbed elbows with Christian patriarchs and archbishops in the Holy Land, forged a friendship with the bishop of Brooklyn by penning a letter.

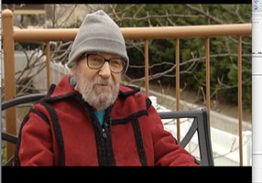

Michael Bobrow, 85, deeply believes in the necessity of interreligious dialogue and collaboration.

This well-versed polyglot historian and journalist looks at modern America through historic terms and comes to this conclusion: The greatest threat the country is presently facing is the American Holocaust, the killing of 55 million unborn children.

“It is a holocaust,” he said. “These are human beings that are being killed and murdered.”

It is a cause so dear to his heart that he endeavors to engage in dialogue with various religious leaders.

“God is paramount in my life,” said Bobrow, who currently resides in a Canarsie assisted living facility.

He goes to Catholic Mass at the retirement home, though he has no intention of converting. There, he was introduced to The Tablet. He began reading the paper and decided to write a letter to the editor, which was published in October 2007 under the title, “Common Spiritual Grief.”

Seeing his name in print in the Catholic paper encouraged Bobrow to go a step further and write to the bishop of Brooklyn, not really expecting a response.

Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio was intrigued. He was amazed by Bobrow’s knowledge and wisdom and quickly developed a deep respect for the letter writer. The bishop wrote back and Bobrow responded in kind.

Of course being the bishop of one of the most populous dioceses in the country requires Bishop DiMarzio to read much physical and electronic correspondence, much of it important communications regarding the running of the diocese.

Reading Bobrow’s letters is something the bishop looks forward to.

“It’s a letter you want to read because you’re going to learn something,” Bishop DiMarzio said with a chuckle. He is impressed with Bobrow’s grasp of world history and his own family history.

In his office, the bishop keeps all of Bobrow’s letters in a thick folder, neatly organized.

The bishop flipped to one, and with a smile, read out loud:

“In Tsarist Russia my family was pro-monarchy, my great grandfather [—], is an honored person, honored by Tsar Alexander III in the royal palace for his service to the state,” the bishop said and chuckled with appreciation: “I mean, you know, it’s unbelievable.”

Bishop DiMarzio wanted to meet the man behind the words and express his respect to the man he has come to admire. Around Thanksgiving the bishop paid Bobrow a visit, hoping his visit could bring some joy. He had not announced himself, and Bobrow assumed that it was a priest from nearby Holy Family Church.

Bobrow warmly recalled that interaction: “I said, ‘Oh hello, Father, may I ask who I’m speaking with?’ And his excellency said, ‘I’m Bishop DiMarzio’ and I said ‘wow’ – a totally pleasant, very pleasant surprise.”

Bobrow said it was as if the pope himself had paid him a visit. The two men spoke fondly of classical music, the Italian language, history and, of course, abortion.

Bobrow views the Catholic Church as a protector of the people. He said even though relations between Jews and Catholics have been strained and violent throughout history, especially in Europe, the Church itself was a protector of the people. He explained that during the Crusades when Jewish people were targeted by mob violence, the pope declared his protection of the Jewish people and their rights.

In modern times, Bobrow believes the Catholic Church is still a protector of the people, this time of the unborn who are persecuted and killed. He sees Bishop DiMarzio as a strong ally in this fight against injustice.

“I consider him a friend of the country, a friend of the people,” Bobrow said of Bishop DiMarzio.