First in a series

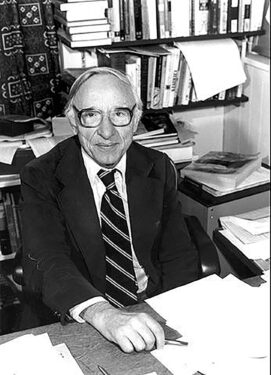

I can recall the first time I heard the name of theologian Bernard Cooke. A classmate of mine in the major seminary left the seminary in his third year and went to Marquette University in Milwaukee to pursue a master’s degree. Soon my friend was writing to me about a young Jesuit priest who was the moderator of the sodality. Not only did my friend praise Bernard Cooke but he sent copies of some talks that Cooke delivered to the members of the sodality. The talks were special, filled with wonderful insights.

A few years later Cooke lectured at Fordham and I made sure I attended the lecture, which was exceptionally good. When my bishop sent me to Marquette to pursue a doctorate in philosophy so that I might teach in a four-year college seminary he was planning to build, I knew that once I became settled at Marquette, I would try to meet Cooke.

The first day I went to register for classes I discovered that in going for the required 30 credits for the doctorate I could use six of those credits for a minor in another subject. I minored in Bernard Cooke. The two courses I took with him — one on grace, one on priesthood — were the two best courses I have ever taken and Cooke was the best teacher I ever had.

During the pandemic I have frequently looked through my bookcase. Finding Cooke’s book, which I had not looked at from the time I first read it, probably 40 years ago, seemed like a special grace. It was like meeting an old friend. When I read Bernard’s words, I could hear his voice. When I read the title I immediately thought of two statements I make to students early in the “Introduction to the Philosophy of Person” course I teach at St. John’s.

First I say that the entire course is an attempt at answering one question: “ ‘Who am I?’ We are going to spend three months trying to answer that question.” Then I suggest that a better question might be, “Who are we?” Bernard Cooke wrote an entire book offering not a philosophical answer to that question but an answer springing from Catholic faith. Stressing that Jesus came to lead us to a profound freedom, to liberate us from our sins, Cooke wrote the following:

“Our own experience of human love teaches us that love is profoundly liberating. Love lays on us responsibilities of the most demanding sort; it requires us to share the thing to which we cling most tightly, our own self; it brings with it risks that are more frightening than any others in our lives. But it is love that frees a person to be truly honest and genuinely himself; it vitalizes his experience so that he lives fully; it stimulates and brightens his consciousness and his thought. Truth will make a man free, but a man must love truth before he seeks it. Knowledge is liberating, but the most important kind of knowledge is knowing other persons, and one cannot truly know another person unless he loves him.” (p. 12)

Jesus came to invite us into a loving relationship with his Father. He did not come to give us a set of rules but to tell us about how much God loves us and to illustrate that love through his teaching, miracles and ultimately through his death and resurrection. My guess is that most people who will read this column received Jesus’ message through the Catholic Church. That message was filtered to us through popes, bishops, priests, our family, teachers and many other channels. Perhaps many who communicated Jesus’ message to us did not communicate it in all its richness.

Jesus’ message has come to be called the good news. I think some in the Catholic schools I attended to some extent distorted the message. For example some of those from whom I learned may have neglected emphasizing God’s love for us and instead emphasized the dangers of temptation and sin. I am not blaming anyone for any distortion of Jesus’ message that was taught to me. My teachers were teaching me what they were taught. I hope I am forgiven for any distortion of Jesus’ good news that might have crept into my preaching or teaching or writing.

The Church is a community, the Body of Christ in the world. We depend on Christ and on one another. Christ is holy and his Spirit is the soul of the Church. Members of the Church do not redeem one another but we can cooperate with the Holy Spirit and play important roles in one another’s lives.

Living in the Christian community as lovingly and as unselfishly as we can offers us a special opportunity to do God’s will and to experience God’s love.

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, every Tuesday at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.

This brought back so many wonderful memories of my classes as a freshman and sophomore at Marquette (1963-65) where I, too, “minored” in Fr. Cooke. I have been forever indebted to him for showing me an expansive faith, one filled with possibility rather than prohibition.