Sixth in a series

If there is one thought that has been going through my mind during the last six weeks as I have been writing this series, it is the very important vocation each person has to participate in God’s sanctification of the world. We do not redeem people. Jesus did that through his life, death, and resurrection and is now lovingly present to everyone.

However, we can share in Christ’s redemptive presence. No person has an unimportant vocation or role. Every person is called by God to contribute. There are no unimportant vocations.Both John Haught and Pierre Teilhard, S. J. in their writing emphasize this. No one is called to be completely passive. In his “The Divine Milieu” (Harper & Row Publishers, 1960) discussing the importance of human action, Teilhard writes the following:

“Each one of our works, by its more or less remote or direct repercussion upon the spiritual world, contributes to perfect Christ in his mystical totality. That is the fullest possible answer to the question: How can we, following the call of St. Paul, see God in all the active half of our lives? In fact, through the unceasing operation of the Incarnation, the divine so thoroughly permeates all our creaturely energies that, to encounter and embrace it, we could not find a more appropriate milieu than that of our action.

“To begin with, in action I cleave to the creative power of God; I coincide with it; I become not only its instrument but its living prolongation. And since there is nothing more personal in a being than its will, I merge myself, in a sense, through my heart, with the very heart of God.” (p. 31)

For some reason, as I am writing this column today I have been thinking of the homilies that I deliver whenever I celebrate a Sunday Eucharist. The way I usually prepare for a homily is that I start by going over the Scripture readings for the Mass. As I reflect on them I try to find one or two points that I draw from the readings that I think I should emphasize in my homily. I think that in my homilies I tend to be positive, emphasizing God’s love for us rather than our sinfulness. When I deliver the homily I frequently discover that I am stressing points that I think I need to hear. I wonder if this is the experience of other homilists.

I hope in some future homily I will be able to communicate Teilhard’s absolutely beautiful insight that when we act according to God’s will, we not only become instruments that God can use to build God’s Kingdom but that through our hearts we merge with the very heart of God. What does this merging mean? It does not mean that we become God. Teilhard was not presenting a pantheistic doctrine. It means, I think, that our union with God, our relationship with God has become closer, more intimate. This may be what St. Paul was urging when he wrote that we should put on the mind of Christ (Phil 2:5) or when he proclaimed that he no longer lived but that Christ lived in him (Gal 2:20).

Stressing that we can meet Christ in actions that we may think of as insignificant or as having nothing to do with Christ, Teilhard writes the following:

“Nor does he blot out, in His intense light, the detail of our earthly aims, since the intimacy of our union with him is in fact a function of the exact fulfillment of the least of our tasks. We ought to accustom ourselves to this basic truth till we are steeped in it, until it becomes as familiar to us as the perception of relief or the reading of words. God, in all that is most living and incarnate in Him, is not withdrawn from us beyond the tangible sphere; He is waiting for us at every moment in our action, in our work of the moment. He is in some sort at the tip of my pen, my spade, my brush, my needle, of my heart and of my thought.

By pressing the stroke, the line, or the stitch, on which I am engaged, to its ultimate natural finish, I shall arrive at the ultimate aim towards which my innermost will tends. Like those formidable physical forces which man contrives to discipline so as to make them perform operations of prodigious delicacy, so the tremendous power of the divine attraction is focused on our frail desires and microscopic intents without breaking their point.” (pp. 33-34)

Reading Teilhard has helped me to appreciate in a new way the depth and beauty of the Little Flower’s belief that grace is everywhere.

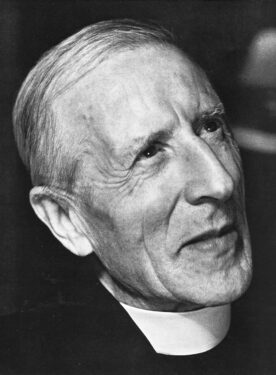

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, 10:30 a.m. Monday through Friday on NET-TV.