Backers of Pete Panto want to mark his plot

CARROLL GARDENS — In the late 1930s, Pietro “Pete” Panto mobilized thousands of fellow longshoremen in Brooklyn to fight corrupt union bosses who were in league with kickback-collecting mobsters.

His name may not be as widely known as other labor leaders like “Mother” Jones, Eugene Debs, or César Chávez. But unlike them, Panto died for his cause, the victim of a suspected mob hit.

He is buried — in an unmarked grave with no headstone — in St. Charles Catholic Cemetery on Long Island. Now, a group of history buffs and descendants of those who remember Panto’s legacy want to correct that.

[UPDATE: Headstone finally posted. Read the Oct. 3, 2023 story here.]

Dr. Joseph Sciorra, a Manhattan-based folklorist, is one of them. He said people didn’t talk openly about Panto after his abduction and murder. Thugs working for the mafia hit squad, “Murder Inc.,” threatened anyone who tried to fill Panto’s place.

“At the site of his burial, he’s erased as well,” Sciorra said. “There’s no marker there. It just seems particularly cruel.”

Sciorra is one of the directors at John D. Calandra Italian American Institute of Queens College, City University of New York. The institute has set up a GoFundMe page to raise $7,450 for Panto’s headstone. As of March 23, the effort had $3,688 worth of pledges.

“People don’t know about the corruption on the docks during that first half of the 20th century,” Sciorra said. “Panto represents this history. But he also represents Italian-American history, labor history, and New York City history.

“If we could do one thing, it should be to get a tombstone or a marker on his grave.”

Tough But Not Bulletproof

The son of immigrants, Panto was born in Brooklyn. However, he spent much of his childhood in Sicily, his family’s homeland. He returned to the U.S. and became a longshoreman on the docks stretching from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to Red Hook.

The waterfronts of Manhattan, New Jersey, and Brooklyn became significant commerce portals via the shipping industry during the 20th century.

“New York came to be because of its harbor and because of the Erie Canal connecting it to the rest of the country,” Sciorra said. “But the docks were the life source for New York City. Everything came in and came out of them.”

Longshoremen loaded and unloaded cargo from ships. The work was risky, with an accident rate second only to lumberjacks, Sciorra said. They were strong and tough but not bulletproof.

Their labor union, the International Longshoremen’s Association, was also controlled by organized crime.

“It was a highly corrupt organization beginning with the ‘shape-up’ system,” Sciorra said. “You’d line up to be picked for a job, and a lot of that had to do with whether you had been playing by the rules — whether you had been sending, not only your union dues, but also kickbacks to the union.”

Sciorra said another rule was a worker’s patronage of businesses or venues controlled by the mob.

“So,” he said, “if you needed a haircut, you needed to go to this barber because that barber was kicking back money as well to the mob.”

Dov’è Panto?

Panto denounced the corruption in waterfront rallies that attracted thousands of dockworkers. They subsequently formed the Brooklyn Rank and File Committee to protest the shape-up system and kickbacks.

“And because of that,” Sciorra said, “he was assassinated.”

Sciorra said Panto went to a meeting with union officials on July 14, 1939. Police recovered his body from a chicken farm near Lyndhurst, N.J. He had been missing for 18 months.

A mob hitman, Abe Reles, gave investigators information about his mobster boss Albert Anastasia, a co-founder of Murder Inc., Sciorra said.

Reles claimed Anastasia ordered Panto’s death and other crimes. However, the case fizzled when Reles was found dead below a Coney Island hotel-room window where a half-dozen sleeping policemen were supposed to guard him.

“It was a harrowing story,” Sciorra said, “and it had its chilling effect on labor activism at that time.”

Still, his Italian followers honored him covertly on the docks with chalk-scrawled graffiti messages: Dov’è Panto? — “Where is Panto?”

Bold, Brave, and Idealistic

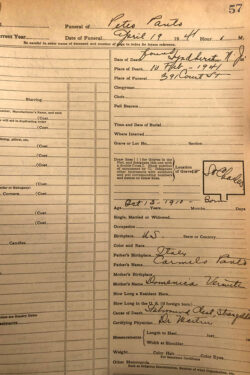

John Heyer, a lifelong resident of Carroll Gardens, heard about Panto as a child. He learned more working at his family’s business, Scotto & Heyer Funeral Home.

“My Aunt Terry (Scotto) is 97, and she remembers the neighborhood was mostly longshoremen who lived here,” Heyer said. “So when Pete Panto disappeared, they were very upset. And when his body was found, it was a big thing.”

Heyer said the funeral home’s log recorded investigators’ official cause-of-death: “stab wound, chest; strangulation.”

The funeral home’s founder, Pasquale “Patsy” Scotto, ignored the mob to help Panto’s family have the funeral at historic Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary & St. Stephen Roman Catholic Church in Carroll Gardens.

“Mr. Scotto knew that this guy was trying to do the right thing,” Heyer said, “and felt bad for the family who lived here on Sackett Street. And now they had no way to bury the young man. So, that’s why he kind of stuck his neck out.

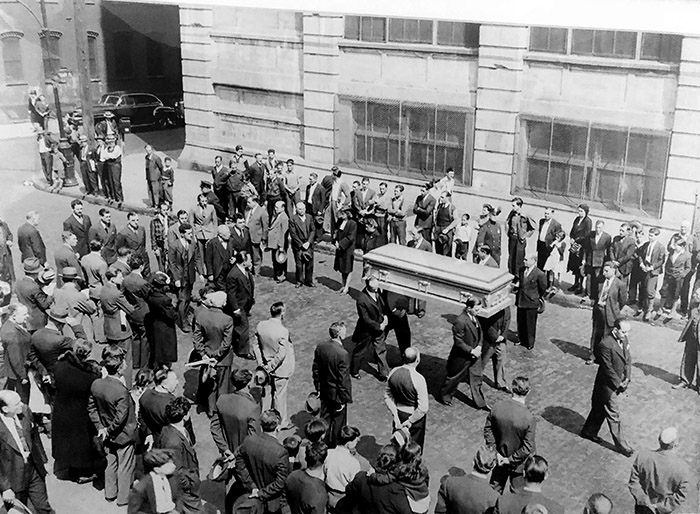

“He paid for the whole funeral. And there’s a great photo of him actually leading a very public kind of funeral procession (for Panto) in the middle of the street.”

Since Scotto covered the funeral and grave costs, Panto’s parents only had to pay for the headstone. But, they returned to Sicily, Heyer said.

A couple of years ago, Sciorra searched for Panto’s grave to pay respects. The cemetery’s records directed him to the plot, where he was shocked to see there was no headstone.

Sciorra resolved to fix that but learned he had to get permission from the grave’s owner — the heirs of Patsy Scotto. That brought him in contact with Heyer, and the quest for Panto’s headstone accelerated. Heyer said his Aunt Terry has been signing paperwork to allow the project.

Resolving that oversight is essential, Heyer said.

“People talk about Italians being mafia,” Heyer said. “And in truth, yeah, there was a criminal element. But this guy was an Italian who was standing up for labor rights.

“He had to have been bold, brave, and very idealistic. What else would drive you to the point of really putting yourself in harm’s way?”

People like Pete Panto should not be forgotten. Stories like this ensure their immortality.