NEW YORK — When filmmaker Martin Doblmeier considers the interfaith growth between Catholics and Jews, Pope Francis’ October 2018 Angelus prayer for the 11 victims of the shooting at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh comes to mind.

It’s a moment Doblmeier doesn’t know would have happened had it not been for the 1965 Vatican II document on interfaith relations “Nostra Aetate,” and in particular, the contribution and influence of 20th-century theologian Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

“I don’t think that necessarily would have happened had there not been an opening and a total transformation of the Catholic church’s understanding of working together and having a sense of value in other faith traditions,” Doblmeier told The Tablet. “It’s a concrete example of how the world has really changed and I think Heschel’s stamp is all over that moment.”

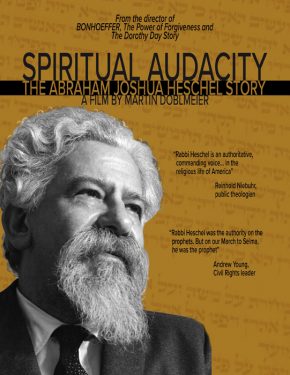

Earlier this month — which is Jewish American Heritage Month — Doblmeier released his latest documentary, “Spiritual Audacity: The Abraham Joshua Heschel Story,” that illustrates Heschel’s commitment to moral issues, justice, and interfaith dialogue through his involvement in the Selma to Montgomery march, anti-Vietnam War activism and “Nostra Aetate.”

Heschel was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1907. He received a Ph.D. from the University of Berlin in 1933 and stayed in Germany until 1938 when he was arrested and deported under the Nazi regime. In 1940, he emigrated to the U.S. with a visa secured by the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. His mother and three sisters all died in the Holocaust.

Heschel’s status as a renowned theologian grew from there, especially through the publication of his books The Sabbath (1951), and The Prophets (1962).

In 1962, Pope John XXIII summoned Catholic leaders to Rome for Vatican II, where they wrestled with issues intended to connect the church to the modern world. Chief among them was the church’s relationship with other faiths, particularly Judaism.

The American Jewish Committee was invited to consult on an interfaith relations document that became “Nostra Aetate,” and its leaders chose Heschel to lead the dialogue. Great progress was made through what became a sincere friendship between Heschel and Cardinal Augustin Bea, head of the Secretariat for Christian Unity. However, it wasn’t always easy.

After Pope Paul VI took over the work of the council in 1963, following John XXIII’s death, a second draft of the document called for the eventual conversion of the Jews, which Herschel rebuked.

“I would rather go to Auschwitz than give up my religion,” Heschel said at the time.

Heschel flew to Rome to meet with Paul VI on the topic, who left the decision up to the council. The rest was history.

“They had several days of debate about precisely this document. The thousand or so bishops actually got up one after another and they spoke,” John Connelly — author of “From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965” — said in the film.

“Virtually all those who spoke out in favor of a strong document condemning antisemitism and going back to the earlier document that had distanced itself from the agenda of conversion,” he continued. “I think they had Rabbi Heschel’s words ringing in their ears.”

The result was “Nostra Aetate” being approved on October 28, 1965. It called for mutual respect and understanding between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people, denounced antisemitism, called for fraternal dialogue between the two faiths, and did not call for the eventual conversion of Jews.

In the film, historian Taylor Branch called it “a tremendous moment for religious history.”

In a conversation with The Tablet, Doblmeier also acknowledged the rocky state of Catholic-Jewish relations to that point and the role of Heschel in moving those relations forward.

“I’m sure in the 1930s Heschel could sense that there was not going to be a lot of vocal support coming to the Catholic church and yet, 30 years later, he has the courage, the conviction, to offer his support and willingness to participate in the transformation of the Catholic church at a time when the church is actually calling out itself, challenging itself to turn into a church that really can face the modern world,” Doblmeier said.

Months before “Nostra Aetate” was approved, Heschel marched hand in hand with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, the late Congressman John Lewis, and others in the Selma to Montgomery march to support black citizens’ right to vote. He also advocated against the Vietnam War.

As Shai Held, co-founder of the Mechon Hadar educational institute notes in the film, Heschel’s commitment to action in part stems from the lack of action from the world against the Nazis.

“He had an incredibly keen, almost excruciating sense of the moral consequences of indifference. The Jews were murdered, no one did anything,” Held said. “He saw his own war on indifference as a kind of reaction to the horror of living in a world where indifference was rampant.”

Doblmeier called Heschel’s stance on indifference a lesson he left for all people of faith.

“If there’s one legacy left to us by Abraham Joshua Heschel it is that indifference is its own form of sin. A person of faith cannot respond by being indifferent,” Doblmeier said.

“Spiritual Audacity: The Abraham Joshua Heschel Story” is available to watch on the websites of local PBS stations or it can be purchased on Amazon and journeyfilms.com.

The documentary completes Doblmeier’s Prophetic Voices trilogy on religious visionaries, social activists, and peacemakers who shaped 20th century America. The first two films highlighted Howard Thurman and Dorothy Day.