Sidney Poitier, ‘Amen’ stole the show in ‘Lilies of the Field’

By William Schmitt

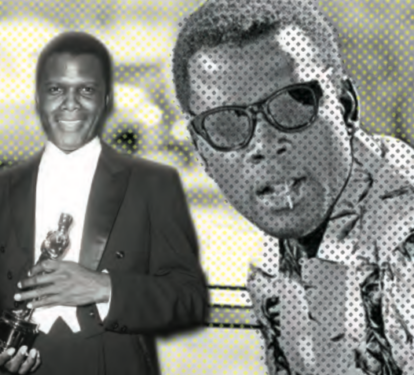

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — The death of Hollywood luminary Sidney Poitier in January reminded Americans of his important and inspiring legacies, including the first leading-performer Oscar bestowed on a black person and the 1963 film tied to that victory. “Lilies of the Field” explored the country’s weakness and goodness in a parable-like drama.

But another “star” of that movie was a gospel song from the African American tradition. Its return from an earlier recording spoke to the wider culture not only about Jesus’ journey from birth to resurrection, but about a bridge of hope over divisions during the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

The song, alternatively called “Amen” or “Amen, Amen” or “Amen (See the Little Baby),” kindled a bonding experience with a group of German nuns in the Arizona desert when sung by Poitier’s character, Homer Smith. Like the stern nuns who ultimately started clapping along, a wide range of singers, actors, and groups seeking inspiration have bonded with Poitier’s film invocations of values like justice and solidarity.

Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions, early in their influential R&B and blues reign, added “Amen” to their 1964 album, “Keep on Pushing.”

Harry Bellafonte and a gospel choir used “Amen” to close out the 1992 ceremony presenting Poitier with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute — a celebratory performance accessible online. Another video from that event shows Denzel Washington calling Poitier “a source of pride for millions of African Americans.”

The song’s impact has continued to spread. Renditions of “Amen,” or at least its central lyric, came to the Catholic Church, possibly entering celebrations of “folk Masses” in the years following “Lilies of the Field.”

“Amen” is non-Catholic Christian at its roots and may be absent from parish hymnals, but the song (as written for the film by Jester Hairston) has provided an energetic tune for congregations proclaiming the Great Amen, which concludes the liturgy’s Eucharistic Prayer. Other immigrant groups have found the song integrates their experiences and musical styles into their Catholic prayer.

“I’ve heard Hispanic groups singing it,” said Jonathan Fields, music director at the Basilica of Regina Pacis, Bensonhurst. “They took it in.”

Although Fields, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, declines to read the musical minds of groups with other backgrounds and faith perspectives, he said various adoptions and evolutions of music reflect an American tendency to blend genres. It’s a path toward the goal of combining personal input and unique dignity with the “common humanity” called for by leaders like the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., he said.

The basilica parish is known for its performances of European masterpieces. That repertoire, focused on melody, has been supplemented by “another expressive dimension” from music emphasizing strong rhythms and group participation, styles like those of Africa and African American spirituals, Fields said.

Poitier, honored with an Academy Award for Best Actor, saw film as an expressive dimension for his own values; he was quoted as saying he “had chosen to use my work as a reflection of my values,” which included the “essential value of every human being.” It made this former Catholic, raised in the Bahamas, a powerful voice for civil rights.

William Barrett, who wrote “Lilies of the Field,” was a New Yorker-turned-Coloradan and an active Catholic. Writing in the Colorado Springs Gazette days after Poitier’s Jan. 6 death, Vince Bzdek, a close friend of Barrett, said the author’s books were inspired by his religion. Bzdek recalled attending Mass with Barrett: “Every Sunday, our priest used to lead us in singing the come-to-meeting-house spiritual that Poitier’s character teaches the nuns in ‘Lilies’—“A-a-a-men, A-a-a-men….”

Fields said he got to know “Amen”— and was prompted to watch the film — because of connections to the civil rights activism of his family. The mid-century movement to reform race relations included the singing of spirituals, he explained; their quotations from the Old and New Testaments sustained hope amid injustice, and the enthusiasm of “call and response,” rotating between a leader and the group, built “a sense of belonging.”

“Spirituals are the root of all American music,” Fields said, pointing to jazz and blues and many popular tunes, all undergoing “cross-fertilization” with gospel and folk. Even in the 1890s, Bohemian composer Antonin Dvorak, living in New York and writing the “New World Symphony,” came to see that “the music of the American person” involved “striving for freedom of expression and human dignity,” according to Fields.

He added that the musical group in which he performs percussion and vocals, The Bay Ridge Band, includes spirituals in their concerts along with songs from Italian culture, songs by Bob Dylan, and a wide sampling of Americana, giving voice to “a whole mix of people crying out for something.” Fields said this is one way to share his belief that “Christ is the complete answer in every experience.”