By Cindy Wooden

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Pope Francis knows his appeals for an end to the war in Ukraine carry little weight with Russian President Vladimir Putin, but he also knows he has an obligation to continue speaking out and rallying others to join him in praying for peace.

In April 2021 — 10 months before Putin invaded Ukraine — the pope expressed his concerns about a buildup of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border and an escalation in the fighting between Ukrainian and Russian-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine.

He did the same in December, in January and repeatedly in February as it seemed Putin was serious about launching an offensive.

Emphasizing the seriousness of his concern, Pope Francis did not summon the Russian ambassador to the Holy See, but instead went in person to the embassy Feb. 25.

One week before Putin launched the invasion, Pope Francis told members of the Congregation for Eastern Churches — including Eastern Catholic leaders from Ukraine, Iraq, Syria and Ethiopia — that too often “the warnings of both popes and men and women of goodwill are unheard.”

Humanity, he said, seems to have “an attachment to war, and this is tragic.”

Still, Pope Francis noted, modern popes, beginning with Pope Benedict XV before World War I, have tried to appeal to consciences and to warn of the “useless slaughter” and the unforeseen consequences of going to war.

The pope also spoke of St. John Paul II’s pleas to avoid the war in Iraq.

Those pleas in early 2003 involved much more than public appeals. He sent Cardinal Pio Laghi to Washington to meet with President George W. Bush, and he sent Cardinal Roger Etchegaray to Baghdad to meet with President Saddam Hussein. The United States and its coalition partners launched their attack three weeks later.

Speaking months later about his meeting with Bush, Cardinal Laghi, a former nuncio to the United States, said it seemed clear that Bush had already made up his mind.

The president acted almost as if he were divinely inspired and “seemed to truly believe in a war of good against evil,” Cardinal Laghi told a conference in October 2003.

“We spoke a long time about the consequences of a war. I asked: ‘Do you realize what you’ll unleash inside Iraq by occupying it?’ The disorder, the conflicts between Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds — everything that has in fact happened,” the cardinal said.

But Bush insisted that democracy would be the main result, he said.

Papal appeals for peace and dialogue always look first to the impact violence and war will have on civilians, especially the elderly and children. In military calculations, they are “collateral damage,” but as Pope Francis noted Feb. 27, they are always the first victims of conflict.

The advent of atomic and nuclear weapons at the end of World War II changed papal discourse about international conflicts and is one reason why the war in Ukraine has shocked so many people in Europe and beyond.

Leading prayers for peace Feb. 25, the first day of the Russian offensive against Ukraine, Andrea Riccardi, a historian and founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio, said the conflict “seems to me the biggest war on European soil since 1945, at least for the size of the country it involves and for the fact that it involves a superpower.”

Putin said Feb. 27 that he had put his nuclear forces onto a higher state of alert.

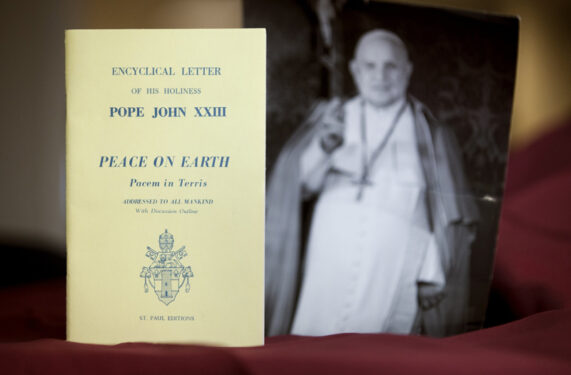

The most thorough papal examination of the folly of war to date is “Pacem in Terris,” published in 1963 by St. John XXIII.

Although it was an encyclical, it was addressed to all people of good will and not just Catholics, and it tried to address people’s hopes and fears at the height of the Cold War and in the wake of the Cuban missile crisis. The pope called for international and interreligious cooperation in the promotion of world peace, emphasizing the importance of human rights and dignity.

In June, the Vatican publishing house released “Peace on Earth: Fraternity is Possible,” a collection of Pope Francis’ words and speeches on the importance of praying and working for peace.

In the final chapter, written specifically for the book, he moved closer than any previous pope had done to adopting a stance of total nonviolence.

Already in “Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship,” he questioned whether in modern warfare any conflict could be judged a “just war” because proportionality and the protection of civilians seem to be difficult if not impossible to guarantee.

“We can no longer think of war as a solution because its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefits,” one of the main criteria of just-war theory, he wrote in the document. “In view of this, it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a ‘just war.’ Never again war!”

And, in “Peace on Earth,” he wrote that nations and factions too easily turn to war, using “any kind of excuse,” including claiming they are attacking another as a humanitarian, defensive or preventative measure, “even resorting to the manipulation of information” to support their argument.

When Jesus was about to be arrested, Pope Francis wrote, he did not claim a right to self-defense and even told the disciple who drew a sword to defend him, “Put your sword back into its sheath.”

“The words of Jesus resound clearly today, too,” he wrote. “Life and goodness cannot be defended with the ‘sword.'”