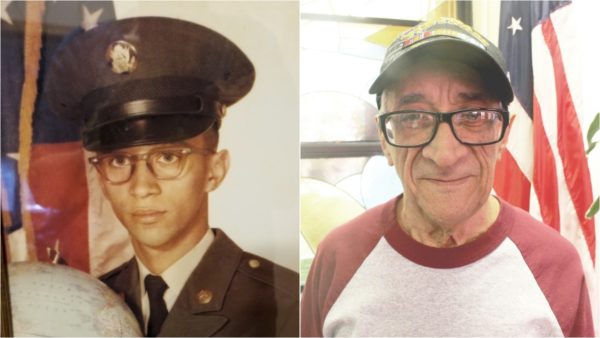

ST. ALBANS — Jose Aponte, a Vietnam War veteran and longtime parishioner of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Williamsburg, moved into St. Albans Community Living Center, a long-term care facility operated by the V.A. NY Harbor Health Care System (V.A. NYHHS), in March.

There, he receives round-the-clock care for his post-traumatic stress disorder and cases of pneumonia and fevers. A month ago, he was put in the hospice unit.

Aponte, 70, a Purple Heart recipient who had two tours of duty in Vietnam, has been battling PTSD for 47 years, and has been in and out of hospitals operated by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs since being discharged from the U.S. Army in 1972.

As Veterans Day on Nov. 11 approaches, Aponte’s health struggles are reminders both of the sacrifice he and countless other veterans have made to keep the United States safe and free and of the sprawling V.A. medical system that treats them at home.

More than nine million veterans are enrolled in the V.A. health-care program nationwide. Locally, the V.A. NYHHS operates three hospitals in New York City, including one near Fort Hamilton, an Army installation in Bay Ridge, and the center in St. Albans, where Aponte now lives. The other hospital is in Lower Manhattan. It also has clinics in Harlem and Staten Island. In fiscal year 2019, which ended in September, the V.A. NYHHS saw 48,117 patients.

According to the latest annual survey from The Wounded Warrior Project, a veterans service organization, while employment opportunities and overall “quality of life” have improved, many veterans like Aponte still face serious physical and mental health issues.

The survey of 36,000 veterans said that 91 percent of veterans live with physical injuries and mental health problems. The most common are PTSD, depression, anxiety and traumatic brain injuries. Meanwhile, a third of veterans reported recent suicidal thoughts, the survey said.

After Aponte was discharged from the military, he had a hard time finding a job, but was able to serve his parish with his “handyman” skills, helping to rebuild things around the church and school. He also worked at a car repair shop with other veterans.

“Back then, places didn’t recognize PTSD or the [Agent Orange] chemicals poisoning soldiers’ lungs, so he had minimal pension,” said Aponte’s wife, Lucille. “It was hard for him to get work.”

Before moving to the St. Albans facility in March, Aponte lived at home, while getting outpatient care.

“We had been going to different facilities and centers, but over time we noticed the oxygen levels and the PTSD was getting worse,” said Lucille, who explained that Aponte was transferred from Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan last year into the V.A. system after a long process trying to get in.

“A lot of the private nursing homes were denying [Jose] because people don’t want to deal with the PTSD. But at the V.A., everyone already knew his case,” she said.

At St. Albans, Aponte finds solace in his Catholic faith. He especially likes the interfaith chapel at St. Albans, where Masses and other services are held for the veterans and their families twice a week, on Sundays and Wednesdays.

According to V.A. NYHHS, 50 to 60 percent of the veterans served in the local V.A. hospitals and clinics are Catholic.

Lucille says that it’s important she and Jose go to Mass together every time. “Having a Catholic part in this whole health care process — it’s a continuation and celebration of our faith,” she said.

Father Andrew Sioleti serves as the chief of chaplains for the V.A. NYHHS, and is a close friend of the Apontes. As one of four Catholic priest chaplains, his regular duties include administration, patient rounds, celebrating Masses and services for vets in the interfaith chapel, and organizing the other 11 interfaith chaplains who serve in the V.A. NYHHS.

Father Sioleti says that working with veterans like Jose Aponte, who struggle with persistent physical and mental ailments, is one of the most “challenging, but life-changing” experiences.

“What this job teaches me every day is to try and walk in their shoes — not that I can, but try, to really enter into the world and be emphatic rather than judgmental,” said Father Sioleti. “The most rewarding thing is to see a dying veteran, who is angry and resentful, reconcile with themselves and with God. If we [chaplains] make one difference for our vets—I know that it’s not me, it’s God doing it.”

Father Edward Conway, the palliative care chaplain at the V.A. St. Albans, added that the work the V.A. chaplains is about helping veterans “experience the end of a meaningful life before they leave this one.”

“It’s both palliative and pastoral care,” said Father Conway. “We help through all [physical, mental and spiritual] distress, to a good death, and be remembered with dignity.”

Veterans and their families seeking assistance, or those with eligibility or enrollment questions, can contact a V.A. Outreach Specialist: Lyn.Johnson2@va.gov, or (212) 686-7500, ext. 4218.

For immediate help, there is also a veterans’ crisis hotline: 1-800-273-8255 (press 1).