FARMINGDALE — Pietro “Pete” Panto, a longshoreman along Brooklyn’s waterfront in the late 1930s, rallied fellow longshoremen against their mafia-controlled union, which marked him for death.

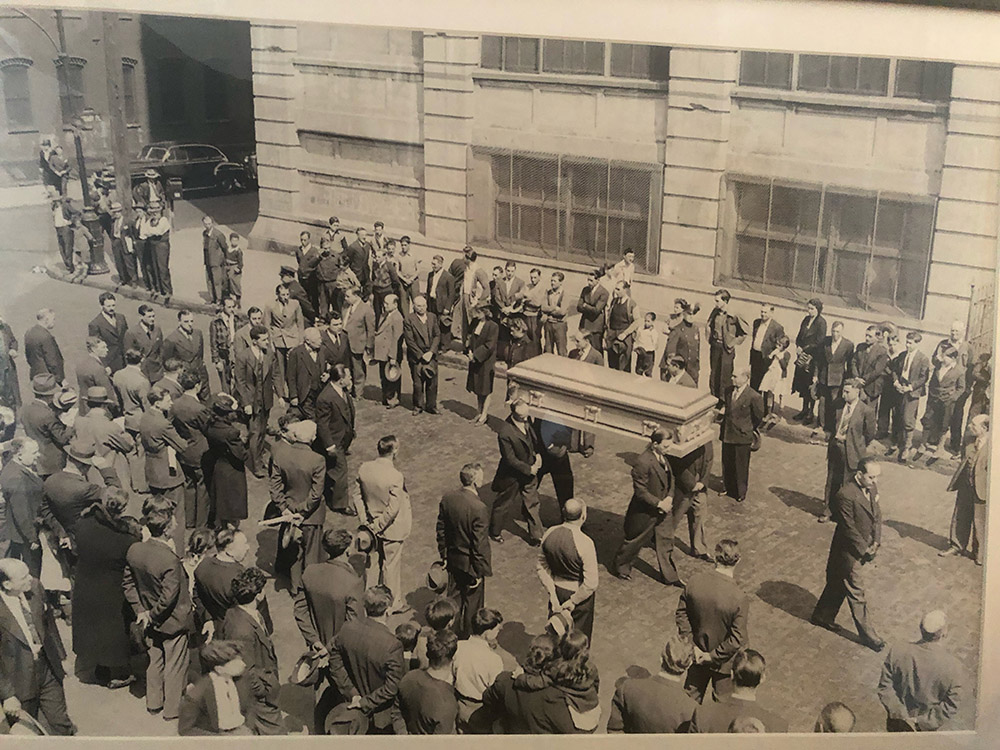

Panto’s legacy could have slipped into obscurity when he disappeared at age 28 in July 1939. Instead, police found his remains nearly two years later at a New Jersey chicken farm where mobsters routinely hid bodies.

The story might have dissolved again with a burial in a pauper’s grave, but Pasquale “Patsy” Scotto, a funeral home owner in Carroll Gardens, paid the expenses, including a gravesite.

Still, historians had a tough time finding Panto’s grave in St. Charles Catholic Cemetery on Long Island; it had no headstone. For more than 80 years, one could legitimately repeat the dockworkers’ rallying cry, “Where is Panto?” — or, in Italian, “Dov’è Panto?”

That changed recently when a headstone finally topped Panto’s grave. Its official presentation was Tuesday, Sept. 26, at the cemetery in Farmingdale.

“Here’s a man who, through his personal charisma, dedication, and hard work, rallied hundreds and thousands of really destitute people,” said Joseph Sciorra. “His murderers were never brought to justice. So it’s an insult to injury to not have a tombstone.”

Sciorra is director for academic and public programming at the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute of Queens College, City University of New York.

The institute, under Sciorra’s leadership, raised $7,450 on GoFundMe to purchase the stone.

Around 70 people contributed from across the nation. Some wrote on the GoFundMe page that their donations honored the memories of fathers and grandfathers who worked the docks.

A couple dozen people attended the stone’s presentation at the cemetery. Among them was Deacon John Heyer, co-owner of Scotto & Heyer Funeral Home — the Carroll Gardens business founded by Patsy Scotto.

Sciorra said during his speech that Deacon Heyer played a key role in the Panto headstone project. The deacon, in turn, recounted Panto’s place in the history of Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens neighborhood.

In those days, the area was heavily populated with dockworkers and their families. But if these guys wanted to work, they had to adhere to a corrupt day-labor system created by their union — the mob-controlled International Longshoremen’s Association.

Panto helped form the Brooklyn Rank and File Committee to protest this so-called “shape-up” system. He organized rallies that drew thousands of fellow dockworkers, which drew retribution from the deadly mob organization, “Murder Inc.”

Deacon Heyer said his Aunt Terry, Patsy Scotto’s daughter, was a child when Panto disappeared. Now at age 98, she still recalls how the crime electrified the neighborhood.

“All around the area,” Deacon Heyer said, “there was graffiti on signs and billboards with the words, ‘Dov’è Panto?’ It became a rallying cry to fight against the injustice of not being able to get fair work.”

Investigators found Panto’s body 18 months after his disappearance, which created a “sigh of relief” in the neighborhood, Deacon Heyer said. Panto’s parents had no money for a funeral, so Scotto, risking mob retribution, paid for everything, except a headstone.

That chore went to Panto’s family, which was not uncommon, Deacon Heyer said. But, he added, the father feared more trouble with the mob, so he moved the family back to Sicily.

The grave had no headstone until the Calandra Institute’s project 82 years later. It actually began during the pandemic when Sciorra went to the cemetery to pay respects to Panto, but was shocked to see it had no monument.

He resolved to change that.

“The most basic human impulse is to have the man’s burial site have a tombstone,” Sciorra said.

The finished product includes a line from an anonymously written poem about Panto. It reads: “This working man from off the docks, our martyr in the fray.”

The name “Scotto” appears at the bottom of the stone to comply with cemetery rules because the plot is owned by the Scotto family. Deacon Heyer explained that his Aunt Terry gladly signed paperwork approving the stone’s installation.

Deacon Heyer praised Sciorra and the Calandra Institute for honoring the memory of Panto and the accurate portrayal of Italian immigrants, not as criminals, but hard-working contributors to the nation’s economy and culture.

“Pete Panto stands for the best of that American dream and that ideal of wanting to better oneself, wanting to find justice for all,” Deacon Heyer said. “These are the stories that I think, as Italian Americans, we need to tell. They’re the ones that really count.”