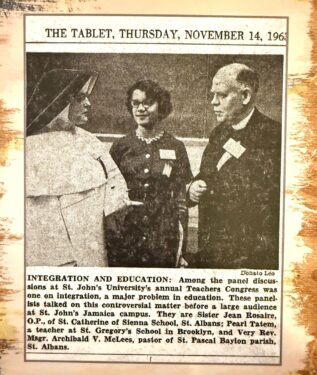

SPRINGFIELD, N.J. — In 1963, Pearl Bernardin, then a third-grade teacher at St. Gregory the Great Catholic School in Crown Heights was invited by the Diocese of Brooklyn’s superintendent of schools to participate in a panel “to discuss the integrated classroom in the parochial school.”

“In view of your experience and interest in this matter, I felt that you would be an articulate and valuable member of this panel,” read the letter, sent to her by the superintendent, Msgr. Eugene Malloy.

“That only goes to show that this was an issue in 1963 that, in the Diocese of Brooklyn, they knew that the schools were not integrated,” Bernardin said, reflecting on the letter.

At the time, Bernardin, now 87, was one of the first black teachers in the diocese. Unbeknownst to her, she would go on to become a pioneer in diversifying Catholic school faculties throughout the metro area.

RELATED: Black Catholics Reflect on 60 Years of the Voting Rights Act and Challenges Today

Bernardin came from an African American family in Bedford-Stuyvesant. There, she attended the predominantly black elementary school at Holy Rosary Parish.

During an interview at her home in Springfield, New Jersey, Bernardin told The Tablet that, as a child, she was “clueless” about racial inequality in the U.S and Brooklyn. She was aware of slavery in the South and the Civil Rights movement in the mid-20th century, but not the deeper history.

During colonialism, Brooklyn existed on a slave-based agrarian economy until New York State outlawed the ownership of human beings in 1827.

African Americans, who were still not entirely accepted in Brooklyn’s larger society, created their own neighborhoods, such as Weeksville and DUMBO. But the Catholics among them had to ferry across the East River to attend Sunday Mass at a welcoming parish in Manhattan.

That continued through the late 1920s when Msgr. Bernard Quinn, now a candidate for sainthood, finally convinced Brooklyn Bishop Charles McDonnell to approve a parish for black Catholics — St. Peter Claver in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Today, that parish, along with Holy Rosary and Our Lady of Victory, forms St. Martin de Porres Parish in Bed-Stuy.

This neighborhood, after World War II, saw an influx of African Americans from Harlem — like Bernardin’s family — plus the “Great Migration” of black people from Caribbean nations and southern states.

RELATED: A Saintly Hero of Black Catholics & Soldiers During Wartime

Bernardin’s elementary school became known as a “black” school because it reflected the neighborhood’s population, not because of segregation. She later attended the school at Our Lady of Good Counsel Parish in Bushwick, which was considered a “white” school.

Meanwhile, in 1954, the Civil Rights struggle began to win social justice in the southern states, including equal education for black children.

But, while “Jim Crow” laws that enforced segregation down south did not exist in New York City, inequality lingered in Brooklyn.

Bernardin said her father, a linotype operator, had to commute from Brooklyn to his job in New Jersey because the labor unions for the printing industry in New York State did not accept black members.

She said her parents didn’t share that with their children until they reached adulthood.

“I guess they shielded us in a way until we got older,” Bernardin said. “Then we started to branch out a little bit, and we found there was a wider world out there, and it wasn’t always friendly.”

Bernardin went on to become a special education teacher for blind students in the diocese. The work carried her to schools throughout Brooklyn and Queens. She said her administrators and fellow teachers were wonderful.

Still, as the diocese worked to integrate the schools, she noticed a different disparity.

“I was constantly on the move,” she said. “But I must say, I never encountered a black classroom teacher.”

Bernardin took a break from teaching to marry and start her own family.

RELATED: How Brooklyn Church’s Pipe Organ Bridges Faith, History

In the 1980s, Bernadin was a teacher at St. Joachim Catholic School in Cedarhurst, New York, in the Diocese of Rockville Centre.

“In that particular school, I knew the principal very well, and we were friends,” Bernardin said. “She gave me a lot of different things to do. She trusted me completely. I was very comfortable.

“One thing, I might say, is that I did not feel as comfortable at those big annual meetings.”

Bernardin said she would look and scan the crowd and see that she was the only African American teacher in attendance.

She then made it her mission to share, respectfully, at every opportunity, why she believed it was essential for everyone to have contact with qualified black teachers.

To that end, Bernardin developed a new presentation titled, “Who Needs a Black Teacher?” She shared the workshops in the Diocese of Rockville Centre and at Molloy University, a Catholic institution in Rockville Centre.

“If I would’ve thought about that question back in 1963,” Bernardin reflected, “I probably would have said, ‘Well, the black children need to see a black teacher so that they can aspire to becoming teachers.’ ”

But later, she said, “I evolved to another level.”

“I thought, ‘Maybe the white parents need to see a black teacher,’ ” she said. “And then finally, before I retired, I came to my last evolution of thought: ‘Maybe it’s the white teachers who need to work with the black teacher and see her as a peer?’ ”

The presentations were well received, as evidenced by the thank-you letters she received from school administrators and leaders at Molloy.

Bernardin, now 20 years retired, said she hasn’t kept up with the hiring practices in the Diocese of Rockville Centre. Still, she is grateful for being heard by those officials and her audience.

These days, the Diocese of Rockville Centre has gone on record as committing to being an Equal Opportunity Employer that does not discriminate based on race, color, or national origin; however, it does require teachers to be Catholic.

When asked if she considers herself a trailblazer, Bernardin said, “I never thought about it that way.”

“I’m a person of faith,” she added, “and so I didn’t set out to be disruptive or to be out there. That’s just not my personality. Maybe the Lord was saying to me, ‘Raise the issue. Never be afraid to raise the issue.’

“Sometimes that’s all you can do, and that’s all the Lord expects you to do,” she added. “Do your best. Do your best when it’s your turn.”

Praise God for Currents and The Tablet. You are always fair in showing the diversity of the Diocese of Brooklyn

and what is going on in parishes. Many thanks to Jessica Easthope and Bill Miller for highlighting the wonderful

Pearl Bernadine and Sr. Thea Bowman, Servant of God. Our Catholic African American community truly needs this spotlight. Many blessings and many thanks!!!!