‘WE’RE TRIED AND TRUE WITH WHAT WE’VE DONE’

DUNWOODIE — In the 1890s, a seminary student in the Archdiocese of New York wrote about how his rector canceled Christmas break, to prepare the future priests for lives of Godly devotion.

The seminarian quoted the unidentified rector. “Young men,” he reportedly said, “you are going to be priests. That means you are going to be soldiers in the army of the Lord. You must break every tie that would make them a temptation against your duty — not only against your duty but against the very highest and best duty you can render to God and souls.

[Related: Opening Mass at Dunwoodie Celebrates 125th Anniversary ]

“If you feel as though you cannot bear it patiently, return to your kindred and your father’s house,” the rector continued. “You are unfit for the service of Him who has declared: ‘He that loveth father or mother more than Me, is not worthy of Me.’ ”

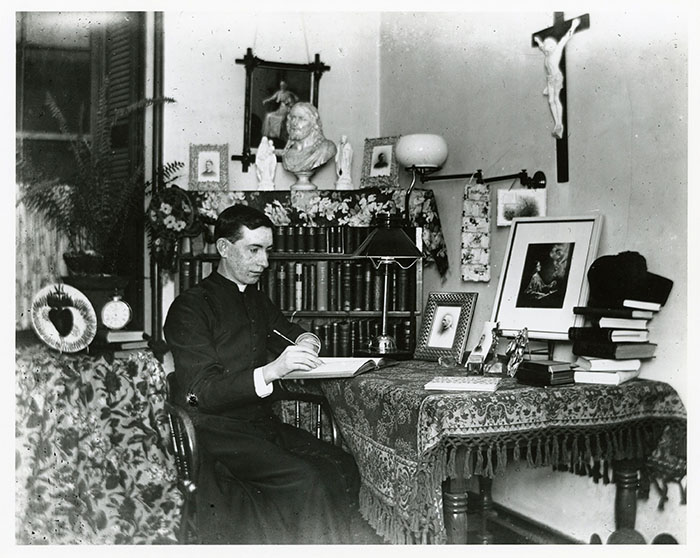

This anonymous report, titled “Leaves from the Diary of a Seminarian,” appeared in the school newspaper, “The Seminary.” It is displayed with other artifacts and memorabilia at St. Joseph’s Seminary & College in Dunwoodie, Yonkers, as part of the institution’s 125th-anniversary celebration.

Festivities began Thursday, Sept. 16, with an opening Mass celebrated by Cardinal Timothy Dolan, archbishop of New York.

The seminary opened on Sept. 21, 1896, on Valentine Hill, a former encampment of Gen. George Washington’s army during the American Revolution. The rector’s “tough love” reflects the seminary’s early reputation for thorough academic challenges and strict discipline.

Kate Feighery, archivist for the archdiocese, said the first seminarians could not leave the hilltop campus for the entire semester. Their days of prayer and studies involved long stretches of mandatory silence in preparation for ministry.

“They were sent from here to so many different situations,” Feighery said. “The archdiocese is so large — you could have gone to Sullivan County or the Lower East Side. And It seems they were so young, but they had a lot of responsibility — like in the parishes that had schools, they were the principals.”

The disciplined seminary life of 1896 contrasted with events outside the seminary’s ornate architecture and granite walls. The “Gay Nineties” were underway, marked by a popular culture considered decadent by older generations. The women’s suffrage movement was taking its first steps.

The New York Telephone Company was formed in 1896. And, in June of that year, Henry Ford completed the “Quadricycle” — a small buggy with a gas engine and four bicycle tires, paving the way for automobile engines.

Unlike their predecessors, today’s seminarians have cars, and they can leave campus during their free time. They also enjoy intramural athletics and jamming with electric guitars and drums.

It’s a sure bet the students of 1896 communicated largely through what today is called “snail mail” — the U.S. Postal System. Modern seminarians can now contact family and friends via smartphones, tablets, and laptops.

Deacon Stephen Robbins of Camden, New Jersey, is on track for ordination at the end of this school year. He is also the “historian” of the institution. He described how telephones gradually evolved on campus.

“Sometimes there was one phone at the director’s office,” Deacon Robbins said. Later, each floor of the residence would have one phone for all to share. “Now they’re in their pockets.”

Deacon Robbins said there are no mandatory periods of silence, although seminarians are expected to be courteous and not raise a commotion while others are trying to sleep or study for finals.

Deacon Colin Lamnitzer of Bridgeport, Connecticut, said the discipline standards of 1896 “seem a bit intense.”

But one must remember “the different time that the Church was in, and the societal norms and expectations of clergy,” Deacon Lamnitzer said. Nowadays “we’re expected to be masters of technology, to utilize that in our ministry.”

When asked if they get homesick, the deacons shook their heads. Digital technology can provide uplifting connections, whether they are lengthy or fleeting. Third-year theology student Carlos Germosen of Yonkers described a recent text exchange with his family:

“You’re good?”

“Yes.”

“OK, good.”

Deacon Lamnitzer confirmed the importance of connectivity.

“At night, I can call my mom and check-in,” and he even FaceTimes his parents. “So that makes it easier to be away from them for prolonged periods of time.”

Today, the seminary sends forth newly ordained priests to several destinations, but it is supported mainly by the Diocese of Brooklyn, the Archdiocese of New York, and the Diocese of Rockville Centre.

“Seminaries sometimes don’t last that long,” said Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of his experience in the Diocese of Brooklyn and beyond. “It’s difficult to maintain them because of the lack of priests to be formators and to be professors. So we had to come to a point where we had to amalgamate, and you play to our strengths.”

He added, “The three dioceses are committed to providing the faculty, but also the students that will make the seminary thrive.”

Bishop DiMarzio looked back at the tools for outreach used during his seminary days 60 years ago.

“All the computerization wasn’t available. We had one little 60-watt light bulb; if you wanted to plug something else in, you had to take that out,” he said. “But today, you see you have all of what’s necessary. It’s a good change. It’s a positive change.”

What hasn’t changed, the bishop said, is Dunwoodie’s devotion to keeping the liturgy at the center of spiritual life.

“We’re not experimenting,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “We’re tried and true with what we’ve done in the past. Then we’ve improved it, adapted it, but it is still the same structure that we had 125 years ago.”

First-year theology student Paul Zwolak of Middle Village, Queens, expressed pride about joining the 64 other students in Dunwoodie last month.

“I’m really happy about it,” he said. “All my fellow seminarians appreciate what exactly we’re doing here, which is to be priests for the future.”

Zwolak said he expects his biggest responsibility will be “explaining and proclaiming the Word of God to the people and just living out our faith.”

“And,” he added, “we do that just by living it out and showing people, Catholics, and non-Catholics, that we live out our faith, and we’re glad of it. We just want everybody else to know that we’re happy to be over here.”

During his homily at the 125th anniversary Mass, Cardinal Dolan described the similarities of seminarians today, 125 years ago, and even in the days of the early Church.

“We’ve got it all in St. Paul’s letter to Timothy,” boomed the jubilant cardinal. “The youthful Timothy — here is his forming” as a student of Paul. “The apostle himself exhorts him to reading, to study, to nurturing the interior gift of his vocation.”

Cardinal Dolan continued with thoughts about Dunwoodie: “Here have come young men, believers, Christian disciples, and committed Catholics. Here they’ve come to discern God’s design for their own earthly pilgrimage, daring to trust that it might even be the priesthood.”

That goal echoed in the seminarian’s diary notes preserved among the St. Joseph’s Seminary and College memorabilia on display for the anniversary.

The 1890s student seemed to have found peace about being away from home on the day before Christmas.

“Last Christmas eve, I was at home,” he wrote. “All the family was gathered about the fireside, in peace, happiness, affection, and goodwill. They are all there tonight, except me. Am I glad I am absent? Yes, I am.”

The seminarian continued: “I thank God that He brought me to this holy house; I thank Him for the strength that He has made me able to tear asunder the ties of flesh and blood. I would rather be a priest than a king. O Lord, make me true to my vocation!”