Brooklyn Priest Explores Cities and Sites Significant in the Struggle for Civil Rights in America

Fifty years after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and a year after racial violence broke out in Charlottesville, Va., one Brooklyn priest made a powerful pilgrimage this summer to cities and landmarks associated with the civil rights movement.

Father John Gribowich recently spent several weeks on the road, traveling to historical sites across the South, and making stops in Atlanta, Ga.; Birmingham, Montgomery and Selma, Ala.; New Orleans, La.; Little Rock, Ark.; Memphis and Nashville, Tenn., and Charlottesville, Va., before ending his journey in Manhattan.

“It was extremely powerful,” said Father Gribowich, who felt the experience opened his eyes and heart to the sin of racial injustice on a deeper level, and helped him realize that he will never be able to fully understand or assume what it is to be a person of color in America.

“Since we live in a country that is very ethnically diverse, it is that way by nature, this trip made me wonder how I understand my role,” he said.

“To me, it was not just so much looking at the past, but more reflecting on myself and seeing where I stand here in the present, especially as a priest.”

Along the way, he learned more about the struggle for civil rights in American history, finding inspiration in the events that paved the way for change and people who stood up for what was right – not simply in the eyes of man, but in the eyes of God.

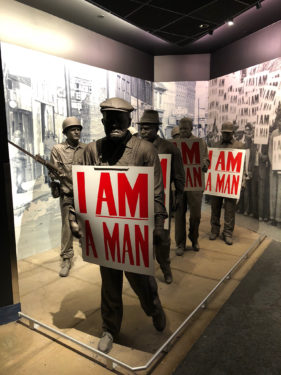

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King was one of those key figures, and Father Gribowich saw several sites associated with the life of the Baptist minister, including Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where the Rev. King was baptized, ordained and served as co-pastor; the door from the jail cell where he wrote “Letter From A Birmingham Jail,” and the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, site of his assassination.

Divine Law Trumps Man’s Law

“Simply by looking at Martin Luther King’s legendary ‘Letter From A Birmingham Jail,’ you see a man of faith referencing … how divine law trumps all other law, especially human law which at times can be a deviation,” Father Gribowich said.

“Divine law simply says as human beings we have a right to exist simply because we are. The fact that we are here means that we have the right to exist and we have equal dignity because of that.”

Problems arise, he said, when people see themselves as – and derive their identities from – something purely human, like skin color or gender, rather than the divine.

“The reality is, the only identity that matters,” he said, “is that we are beloved sons and daughters of a loving Father, and we experience that through Jesus. [Rev.] King knew that.”

While the Rev. King may be the most recognizable figure in the civil rights movement, Father Gribowich said it is important to realize that the Rev. King participated in a long line of prophetic people, since before the Civil War and which continues today.

“Many of us still look at Martin Luther King with his prophetic vision of what humanity should be and we’re inspired by him,” he said.

Along his journey, Father Gribowich visited the home of Medgar Evers, the first NAACP field secretary and civil rights activist; the site of Bryant’s Grocery, where 14-year-old Emmett Till was accused of flirting with a white woman and later murdered; and Little Rock Central H.S., where Daisy Bates led the fight to allow nine African-American students into the all-white secondary school.

One of the sites that stood out for Father Gribowich was the “hallowed ground” of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., where hundreds of civil rights demonstrators were beaten with billy clubs on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, on their way to the state capital in Montgomery.

“It’s such an iconic symbol of the civil rights movement, of people crossing from slavery into freedom. It has almost a biblical parallel to crossing the Red Sea,” he said.

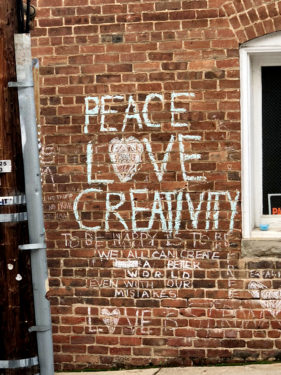

As part of his pilgrimage, the priest made a point to visit Charlottesville, Va., just before the one-year anniversary of race riots there. He took time to walk the streets and remember the sadness and ugliness that happened there just last year.

Still Have Miles to Go

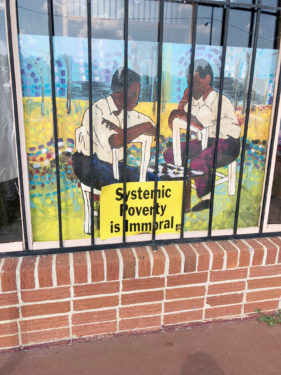

“It is such a sad reminder that we think the civil rights movement solved things but it really hasn’t,” Father Gribowich said. “We are under this illusion that we have moved beyond racial prejudice and discrimination, but the very fact that we think we moved on just makes it even worse.”

The final stop on his road trip was Riverside Church in Manhattan, where the Rev. King stood in the sanctuary and gave his “Beyond Vietnam” speech on April 4, 1967. Being able to stand where the Rev. King once stood up for all people gave strength to Father Gribowich.

The speech, Father Gribowich said, showed the depth of the Southern-born minister. More than a civil rights activist, he was a man trying to preserve and understand the human dignity of all people.

“The civil rights movement is not an isolated movement within the context of the history of the United States. We all need to be striving to recognize the human dignity of all people. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech at Riverside Church against the Vietnam War was showing that the dignity of human rights has to be upheld at every level.”

One way to do that, the priest said, is by fostering openness, compassion and dialogue among people of every race, ethnicity and color.

“If there’s one thing we can all learn from the civil rights movement,” Father Gribowich added, “it is for us to reclaim our true identity as beloved sons and daughters” of God.

Contributing to this story were Matt O’Connor and Timothy Harfmann.

The article “Civil Rights Road Trip,” chronicling the pilgrimage of Brooklyn priest Father John Gribowich to sites associated with the history of America’s civil rights movement, is illustrated by a couple-of-stories-tall “mural of social justice figures in Memphis, Tenn.” apparently on a factory or warehouse wall.

That tribute to individuals prominent in the cause of social justice intriguingly appears to depict what seem to be three Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth, “Sisters of Nazareth” for short, garbed in their traditional habit.

To the far left in the photo of the mural, two of the Sisters, probably seated, flank what appears to be a drain pipe while the third stands between them coyly peering around and past the pipe. Are they indeed Sisters of Nazareth? I know of no other order with an even remotely similar habit.

A predominantly Polish order of nuns founded in 1875, Sisters of Nazareth had since the beginning of the last century, and perhaps even longer, taught generations of students in Polish parish schools throughout the Diocese of Brooklyn. My mother and her siblings as well as I were taught by these Sisters at St. Cyril & Methodius School in Greenpoint.

I know that the Sisters taught at St. Peter Claver School in a predominantly African-American parish in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, but I was never aware of this work having received any wide recognition, surely not enough to place three of the Sisters in this mural in Memphis, as the Sisters surely thought of their mission as nothing extraordinary, as nothing beyond their humble call to service.

Am I mistaken about the extent of the Sisters’ fame? Indeed, am I mistaken about the presence of the Sisters of Nazareth in the mural? I would be most grateful for any information regarding the mural and the identity of the three nuns depicted. If they are, as I suspect, Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth, this mysterious Memphis wall illustrates a fascinating yet obscure Brooklyn connection.

Regards again as always,

Thomas G. Straczynski

Whitestone

Mr. Straczynski-

I am the Communications Director for the Holy Family Province (U.S.) of the Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth (CSFN). Our archivist, Sr. Rebecca Sullivan, brought your comment to my attention. After research in our archives along with some internet research, we have determined that the sisters featured in the mural are not CSFNs. They are Sister Constance and her companions, Episcopal nuns from the Sisters of St. Mary who stayed behind to care for the sick and dying after the yellow fever epidemic in Memphis in 1878. While the habits are similar, they are not CSFNs.

Tammy Townsend Kise

Communications Director

Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth

310 N River Rd

Des Plaines, IL 60016