By Antonina Zielinska

Black Catholics have been part of the Church since Biblical times, said a visiting bishop as the diocese marked Black History Month.

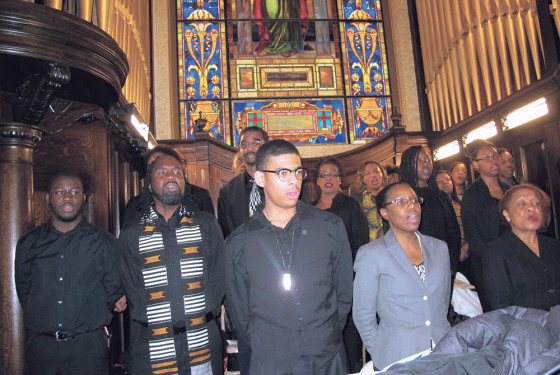

Bishop Shelton Fabre, the Bishop of Houma-Thibodaux, Louisiana, joined the Brooklyn Diocese Feb. 8 for a Mass of thanksgiving at St. Joseph Co-Cathedral, Prospect Heights.

“During this Eucharist, we reflect upon the gifts that black Catholics have brought to the Church,” he said during his homily.

Black Catholics have offered their very selves for the sake of the Church since Biblical times, he said, referencing the Gospel, which clearly mentions the early Church spreading into northern Africa.

This message struck home for Colleen Chasteau, who came to the event at the invitation of her friend. She said people often think of Catholicism as being an exclusively European religion that has been forced on the African continent with colonization. She was thankful to Bishop Fabre for reminding the congregation that Catholicism in at least some parts of Africa, long predates European colonization.

“It makes me prouder to be an African-American and a Catholic,” she said. “It makes me want to share my faith more.”

During his homily, Bishop Fabre said it is also important to remember more recent divides in the Church among white and black communities, not to dwell on the pains of the past but to learn and grow from them.

From Slave to Saint

To help the congregation realize what such growth and healing can bring, the Louisiana Bishop brought forth the example of St. Josephine Bakhita, whose feast day is recognized on Feb. 8, except when it falls on Sundays, as it did this year.

Born in Sudan in 1869, St. Josephine was kidnapped while working in the fields with her family and sold into slavery, an illegal institution at the time. Being sold several times to different owners, her first years of slavery were marked by brandings and beatings. During one instance, one of her captors cut her 114 times and then poured salt into her wounds to make sure scars would remain.

Although she did not know of Jesus Christ at this point in her life, St. Josephine felt a strong calling. In her diary she wrote: “Seeing the sun, the moon and the stars, I said to myself: ‘Who could be the Master of these beautiful things?’ And I felt a great desire to see Him, to know Him and to pay Him homage.”

St. Josephine was eventually taken to Italy where she met the Canossian Sisters. In Italy, she won a court battle that allowed her to stay with the Sisters and entered the convent in 1893.

Her love of God was so strong that she was recorded as saying: “If I were to meet the slave-traders who kidnapped me and even those who tortured me, I would kneel and kiss their hands, for if that did not happen, I would not be a Christian and Religious today.”

Bishop Fabre told the congregation, that as Catholics it is their duty not to give into the finite sufferings of today, difficult as they may be, but to trust in the infinite hope of Christ.

Retired Brooklyn Auxiliary Bishop Guy Sansaricq said it is important to be honest and to acknowledge that the Catholic Church has not always been welcoming to Black Catholics because the events of the past still weigh on the culture of the present and a divide still exists. Understanding the past can bring about healing.

Another reason that the celebration of Black History Month is important, Bishop Sansaricq said, is that it highlights African cultural traditions that have enriched the Catholic Church, such as African and African-American songs of praise. Although individual churches in many areas benefit from these cultural riches, it is good that the American church as a whole emphasizes it in February, he said.

“The Church is a mosaic,” he said. “Diversity cannot be wiped out in the name of unity. Diversity allows unity.”

Lovette Aneke, a Nigerian immigrant, came to the celebration in traditional Nigerian Igbo attire for married women. She was at the event with her husband and three children. She said events such as this diocesan celebration allow all Africans, those who have been in America for generations and those who are immigrants, to celebrate their cultures together. It is also a way to recognize the sacrifice of those who have worked to break racial divides.