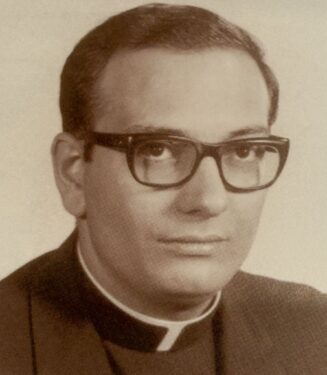

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — In 1970, a newly ordained 25-year-old priest from Newark, New Jersey, became associate pastor of St. Nicholas Parish in Jersey City, but a special job awaited him.

Father Nicholas DiMarzio — a future bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn — was then assigned to help waves of new immigrants get settled in the U.S. They had been pouring into the United States since President Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act five years earlier.

“I always was favorable to immigrants,” said Bishop Emeritus DiMarzio, who retired in 2021. “I came from an immigrant household, so I understood the reality.

“But there were all these new immigrants. Every week, we’d see a new family because they were reuniting with relatives who were already here. And then the Hispanics started to appear too.”

Bishop DiMarzio’s task was to help all of them. More immigrants followed from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

Over the next five decades, he became an authority on immigration. He established aid organizations while also collaborating with government groups. But now, 60 years later, the 1965 act is credited with causing major demographic shifts far beyond the Archdiocese of Newark and the Diocese of Brooklyn.

“It changed the fabric of our country,” Bishop DiMarzio said.

A Swinging Pendulum

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 is part of the swinging pendulum of contradicting American attitudes towards immigrants.

To grasp these diverse positions, consider how Irish immigrants in New York City and Long Island were maligned during the 1800s for their Catholic faith and their willingness to work for cheaper wages, which undercut the native-born labor pools.

Eventually, the Irish gained political and economic power. Meanwhile, the nation expanded, which necessitated a transcontinental railroad to connect the East and West coasts.

Jennifer Gordon, a Fordham University law professor specializing in immigration, described how industries in the mid-to-late 1800s imported labor — much of it from China — to lay rail tracks and produce food.

Golden Era of Immigration

But after the railroad was completed, the nation faced an economic downturn, Gordon said. Labor markets dwindled, and now the Chinese, like the Irish before them, were seen as undesirable competitors for jobs.

In response, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which throttled immigration and naturalization for various Asian ethnic groups, Gordon said.

“We swing from celebrating our immigrant heritage to treating immigrants with violent rejection, over and over, during the course of history,” Gordon said.

RELATED: Walking With Migrants by Bishop Emeritus DiMarzio

Next, she said, came the “Golden Era of Immigration” in the late 1880s through the 1920s when masses of Southern and Eastern Europeans arrived.

“People from Italy, Greece, and a lot of Jewish people fleeing pogroms came in really large numbers,” Gordon said. “And so that generated a new wave of anti-immigrant sentiment.”

Consequently, Gordon said, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which restricted immigration based on national origins.

Big Chunks of Quotas

This new law favored immigrants from Northern and Western Europe through a quota system, Gordon said.

“And the way they did that,” she explained, “was to tie the quotas to the percentage of that population that had been present in the U.S. in the late 1800s. A lot of Norwegians, British, Germans, and other Northern and Western Europeans got big chunks in the quotas.”

Brooklyn was suddenly nicknamed the “City of Churches” as Bishop Charles McDonnell scrambled to establish parishes for these growing ethnic communities.

Meanwhile, Southern and Eastern Europeans got fewer quotas, and most Asians were banned outright, Gordon said.

“That persisted until 1965,” she explained.

But first, she added, the nation’s political leadership needed a shift in attitudes toward immigrants — the same mentality that gave rise to the Civil Rights Movement.

JFK and ‘A Nation of Immigrants’

In 1958, a Massachusetts senator, John F. Kennedy, wrote a book titled “A Nation of Immigrants” in which he recounted the important contributions of foreign-born residents.

The book also called for an easing of immigration restrictions, which was part of his successful 1961 presidential campaign. Johnson picked up the cause following Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. By this time, Italians had begun to gain political power, much like the Irish had done a century earlier.

Bishop DiMarzio recalled how a New Jersey Democrat, Congressman Peter Rodino of Newark, became a leader in Civil Rights and immigration legislation.

Coalition Prevailed

Meanwhile, Johnson enlisted another Democrat, Rep. Emanuel Celler of New York, to co-author the immigration reform act that Kennedy desired.

“He was a Brooklyn guy,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “He saw Jewish people were really excluded. Most were from Poland and suffered during the war, but they were stuck and couldn’t come.

“But, with Rodino interested in the Italians, now you had people in Congress representing these groups, and they worked together.”

The coalition prevailed, and President Johnson signed the act on Oct. 3, 1965, in front of the Statue of Liberty.

A Dramatic Shift

U.S. immigration policies shifted from a quota system to one based on family reunification and skilled labor. Waves of newcomers came from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and finally, Asia, although caps of 20,000 people per year were placed on all countries.

Demographics have since shifted dramatically.

For example, according to Pew Research, in 1965, citizens of European descent made up 84% of the population, while Hispanics comprised 4%. Currently, 62% of the population is white, and 18% is Hispanic.

Pew estimates that by 2065, 46% of the population will be white, and the Hispanic share will rise to 24%.

Welcoming the Immigrant

With the new influx of people, the Church became busy focusing on what it has always been called to do — welcoming the immigrant. In 1973, Bishop DiMarzio visited Brooklyn to observe how it was handling the increases.

He said that he admired the work of then-Msgr. Anthony Bevilacqua, the future archbishop of Philadelphia who served as chancellor of the diocese and as director of its new Migration and Refugee Office.

“They were combining legal services with pastoral services and other things that the immigrants needed,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “It was kind of a holistic approach. So, we tried to imitate that.”

In 1976, Bishop DiMarzio was appointed as the refugee resettlement director for the Archdiocese of Newark, where he also founded and directed the Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLINIC).

Illegal Immigration

Over the years, Bishop DiMarzio has consulted with and worked alongside various organizations on immigration issues, including Congress, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and the United Nations, among others.

Bishop DiMarzio said the 1965 act has served the nation well, but it hasn’t been perfect because it was never adequately updated to increase the caps on entries.

“Unfortunately,” he said, “illegal immigration follows legal immigration. People want to be united with their families. When there’s no ability to do that, you get illegal immigration.”

Meanwhile, Bishop DiMarzio added, the nation has become dependent on imported labor.

He said that of the 11 million illegal aliens in the U.S., 8.5 million are workers. He worries that mass deportations ordered by President Donald Trump could purge the labor force, leading to a recession.

“The border has been secured,” he said. “Perfect. Now secure the workplace. Make sure nobody can work unless they’re here legally and legalize the people that are here.”

Bishop DiMarzio said that has been done before in an effort not led by Democrats, but by a Republican — President Ronald Reagan — who championed amnesty measures in the mid-1980s.

“That’s the solution — very easy,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “I was there in Washington six years, working day and night on that legalization act. And it worked.

“But now, we only have two parties that don’t talk to one another. They only hate one another. So, how are you going to have any compromise?”