By John L. Allen

ROME (Crux) — In his first encyclical “Deus Caritas Est,” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI wrote that Christianity doesn’t begin with an idea or an ethical system, but an encounter with the person of Christ. Personal encounters are indeed foundational to much of Christian history, and yesterday was the 60th anniversary of one of the most consequential such meetings of the last century.

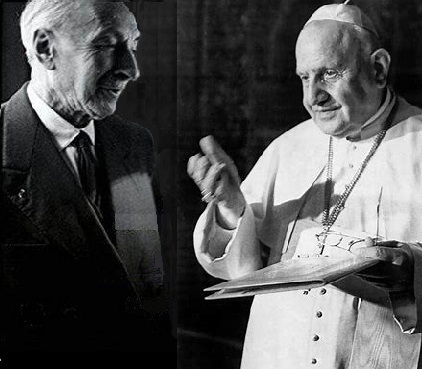

It was June 13, 1960, when a distinguished French Jewish historian, intellectual and educator named Jules Isaac met St. John XXIII in a Vatican audience.

Their conversation triggered a long path of reconciliation between Judaism and Catholicism which reached a crescendo at Vatican II, gathered steam under St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, and continues today under Pope Francis – one sign of which is that a piece yesterday recalling the Isaac/John XXIII meeting in “L’Osservatore Romano,” the official Vatican newspaper, was written by Rabbi Abraham Skorka of Argentina, a close friend and occasional traveling partner of Francis.

By the time he met “Good Pope John,” Isaac was already a well-known pioneer in Jewish/Christian relations, in part because of his friendship with French Catholic poet and essayist Charles Péguy. In 1894, the two men sided with Alfred Dreyfus and continued to support him until his exoneration in 1906.

Together, Isaac and Péguy also campaigned for reconciliation between Christians and Jews, opposing a rising tide of anti-Semitism in France that exploded in the Dreyfus affair. Isaac was also one of the founders of “Amitié Judéo-Chrétienne de France,” an organization devoted to promoting friendship between Christians and Jews, and one of his best-known historical works was a 1947 book titled “Jésus et Israël” exploring the Jewish roots of Jesus.

The June 1960 audience wasn’t Isaac’s first meeting with a pope. He met Pope Pius XII in 1949, presenting the pope with a list of 18 points Isaac believed should undergird Christian education about Judaism, such as “Jesus was a Jew” and “the trial of Jesus was a Roman trial, not a Jewish trial.”

When Pope John XXIII announced his intention to call the Second Vatican Council in January 1959, Isaac thus saw it as a chance to encourage the world’s bishops to take up the issue of Jewish/Christian relations and requested an audience with the pontiff, which was granted a year later as preparations for the council were underway.

Angelo Roncalli, the given name of Pope John XXIII, brought his own experience of Jewish/Christian solidarity to the encounter.

While he served as the ambassador in Turkey during World War II under Pope Pius XII, Roncalli helped save Jewish lives by issuing false baptismal certificates to Jewish children and also helping refugees obtain visas. He also passed along reports to Pope Pius about the annihilation of Jews in Poland and Eastern Europe, based in part upon what Jewish refugees were telling him.

Later, as pope, John XXIII used his first Good Friday liturgy in 1959 to remove the term “perfidious” from a traditional prayer for the conversion of Jews.

According to Isaac’s later descriptions of the 1960 meeting, he presented John XXIII with a dossier containing the results of his research on the history of Christian teaching on Jews and Judaism and its role in fomenting anti-Semitism, asking that a commission be formed to treat the subject at the looming ecumenical council.

The Holy Father’s response, Isaac recounted, was to say, “I already thought about that at the start of our conversation,” and told him he could walk away with “more than just hope” that something would be done.

After the traditional summer break in 1960, Pope John XXIII tapped Cardinal Augustin Bea, a German Jesuit and the first head of the new Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, to form a sub-committee for the council devoted to Christian/Jewish relations. John XXIII’s private secretary, then-Monsignor Loris Capovilla, wrote a 1966 memo to Bea recalling the importance of the encounter with Isaac.

“I remember very well that the pope was deeply struck by that meeting, and he spoke with me about it at length,” wrote Capovilla, later to be named a cardinal by Pope Francis.

“John XXIII had never considered confronting the Jewish question and anti-Semitism [at the council], but that from that day on he was completely committed.”

In one of those historical ironies that can’t help but seem unfair, neither Isaac nor John XXIII would live to see the breakthrough that resulted from their tête-à-tête: The Vatican II document “Nostrae Aetate,” on the relationship between Christianity and other religions with a particular emphasis on Judaism.

Among its watershed declarations were that regarding the death of Christ, “What happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today.” It also said that the Church decries “displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.”

A first draft of the document, at that time entitled “Decretum de Iudaeis” (“Declaration on the Jews”) was approved by John XXIII in November 1961, but the final version with the new title wasn’t promulgated until 1965 under St. Paul VI, two years after Pope John’s death in June 1963. Isaac would die three months after Pope John, in September 1963.

Interestingly, all three lead actors in the drama of “Nostra Aetate” – John XXIII, Isaac and Bea – were in their eighties at the time, proving, among other things, that it isn’t always the young who lead revolutions. In this case, three men brought the cumulative weight of their convictions and life experience to bear and, together, they changed history.

(As a footnote, there was a fourth figure who played a more behind-the-scenes role, an Italian laywoman named Maria Vingiani, who died in January at the age of 98. A native of Venice, she became fascinated early in life by the city’s religious diversity, including its historic Jewish community – it’s actually the Venetian dialect that gave the world the term “ghetto”. Vingiani threw herself into ecumenism and inter-religious dialogue, along the way befriending both Roncalli when he was the Patriarch of Venice and Isaac. When Isaac requested his now-famous audience, Vingiani supported him and strongly advised John XXIII to take the meeting.)

This turning point in Jewish/Catholic relations, like Christianity itself, began with a simple encounter. Perhaps the moral of the story is that one should take every encounter with another person seriously, because you just never know when destiny may be calling.