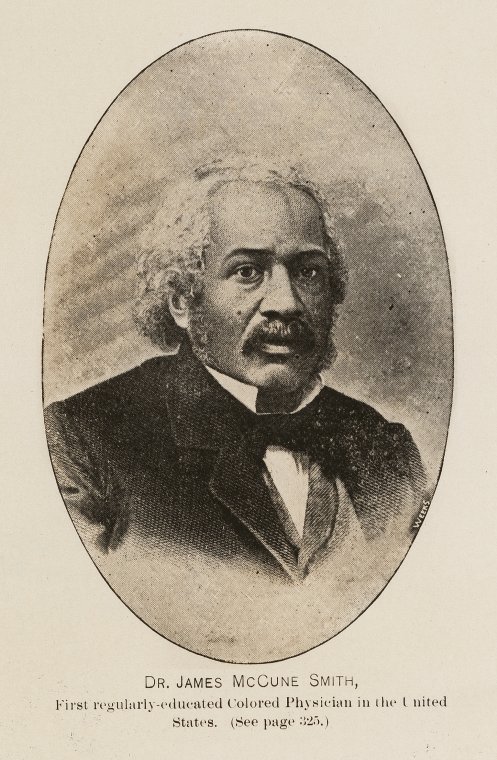

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — James McCune Smith was the first African American in history to earn a medical degree, but not before he was turned down for admission by numerous institutions in the U.S. because he was black.

But Smith, a gifted science student, refused to let 1830s-era racism deter him. He went overseas, enrolled in medical school at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, and graduated at the top of his class. There were more accolades to come; Dr. Smith (1813-1865), was also the first African American to run a pharmacy in the U.S.

Dr. Smith, who lived in Brooklyn for a time and is buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, is one of several African American pioneers in the medical profession whose achievements are attracting attention as Black History Month 2022 is celebrated under the theme, “Black Health and Wellness.”

“Blacks in all fields have overcome a great many obstacles to be able to contribute to this country and that’s certainly true in the field of health care. In many cases, their contributions have been historic,” said Donell L. Barnett, Ph.D., president of the Association of Black Psychologists.

Another 30 years would pass after Dr. Smith received his medical degree before one was conferred on an African American woman. That was Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831-1895), who graduated from the New England Female Medical College in 1864 and set up a medical practice in Boston.

Another pioneer, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895-1934), was the first African American woman to receive a Ph.D. in Psychology, earning her doctorate at the University of Cincinnati in 1933. Her dissertation focused on racism in education. Tragically, she did not get to enjoy the fruits of her success for long. She was killed in a car accident in Louisiana in 1934.

According to Harold S. Koplewicz, president of the Child Mind Institute, the work done by Prosser and others were important building blocks in the fight for racial justice.

“All these pioneers have sought to understand and challenge the troubling history of racism and inequity in mental health care,” Koplewicz said.

A decade before Prosser’s achievement, Francis Cecil Sumner (1895-1954) saw his name etched into history as the first African American man to earn a Ph.D. in Psychology. Sumner, who attended Clark University in Massachusetts, had to postpone his studies to serve in World War I. He returned from the battlefield to earn his doctorate in 1920.

African Americans have been responsible for groundbreaking work, particularly in the field of mental health.

Mamie Phipps Clark (1917-1983), Ph.D., and her husband, Kenneth Clark, Ph.D. (1914-2005), were responsible for one of the most famous psychological experiments ever conducted.

The “Doll Test,” conducted by the Clarks in the 1940s, showed the effects of segregation on children. The study consisted of 253 black children, each of whom was shown a black and a white doll and then asked which one they preferred to play with. The majority of the children replied that they wanted the white doll, saying it was prettier than the black doll.

The fact that the black children deemed white dolls more preferable raised eyebrows. The Clarks concluded that black children formed racial identities early in life — as young as 3 years old — and attached negative attributes to their race.

In the early 1950s, the plaintiffs in the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education cited the “Doll Test” in their arguments as evidence of the damages wrought by school segregation.

“The Clarks certainly played a pivotal role in shaping civil rights legislation and how the country thought about race relations,” Barnett said. “They helped people to understand that the ‘separate-but-equal’ doctrine wasn’t effectively what was happening in the classroom,”

Even in more recent history, there have been black pioneers in the field of medicine. Dr. Joycelyn Elders (born in 1933), a pediatrician from Arkansas, was named U.S. Surgeon General by President Bill Clinton in 1993. She became the first African American woman to hold the post.

Dr. Elders had a controversial and brief tenure as the nation’s top doctor. Her outspokenness and support for the distribution of contraception in schools and the legalization of medical marijuana, as well as her pro-abortion stance, earned her many critics at the time.

She resigned in 1994, after just 16 months on the job. She is still active today and currently serves as a professor of pediatrics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.