WILLIAMSBURG — Among the hundreds of thousands of graves at Holy Cross Cemetery in East Flatbush, there is a simple slab stone bearing a single name — Keely.

Here lies the prolific — yet humble — church architect Patrick Charles Keely, who was 26 when he came to Brooklyn from Thurles, County Tipperary, Ireland in 1842.

Keely had no formal education in architectural design, but he had ironclad skills in construction, carpentry, and wood carving.

Along the way, he developed the ability to design and build more than 600 churches and religious buildings in Canada and the U.S., including, up until the time of his death in 1896, all of the 19th-century cathedrals in New England and 14 Catholic churches in Brooklyn.

“He was an architectural dynamo,” said Joseph Coen, archivist for the Diocese of Brooklyn, who keeps close tabs on parish histories. “He goes from being this young, unknown young man who builds not just ordinary churches but cathedrals across the country.

“That’s a productivity that I don’t think anyone has ever matched here in the United States.”

Keely’s grave at Holy Cross Cemetery is among those of some of the most famous — and infamous — New Yorkers, including financier “Diamond” Jim Brady, Major League Baseball Hall of Famer Gil Hodges, Medal of Honor recipients, and a few mobsters.

Yet, the simple inscription of his last name is a testament to Keely’s humility and fidelity.

In the early 1950s, Francis Kervick, a professor of architecture at the University of Notre Dame, lamented that nearly 60 years after his death, the general public was unaware of Keely’s legacy.

“He was a man who was self-effacing and humble,” Kervick wrote, “and this may have been the reason that he is now so thoroughly neglected.”

Keely listed “carpenter” as his occupation upon landing in 1842 at present-day Battery Park in Lower Manhattan before moving to Brooklyn.

Growing up in a family of well-to-do builders helped the young craftsman develop his construction skills, according to Kervick.

Keely arrived in America three years before the catastrophic Irish Potato Famine, which continued through 1852. It’s unclear if Keely’s family suffered back home, but historical accounts confirm that County Tipperary endured mass starvation and subsequent food riots.

The famine killed an estimated 1 million people in Ireland and forced another million to flee the country.

Irish populations ballooned in Manhattan and Brooklyn, which drew the ire of the political party called the “Know Nothing,” who were nativists that responded with rioting and arson, as depicted in the book and film, “Gangs of New York.”

Still, many of these immigrants were Catholic, which prompted the need for more churches — and priests to pastor them.

Into this mix came the newly ordained Father Sylvester Malone, also from Ireland, in 1844. His only job for his entire priesthood was to pastor a Catholic congregation in Williamsburg, now a neighborhood in Brooklyn.

The parish was called St. Mary’s Church when Father Malone arrived. He renamed it Sts. Peter and Paul Parish, and determined he needed a new building for the growing congregation. He turned to a fellow Irishman he met recently — the carpenter Patrick Keely.

“Together they worked out a plan,” Kervick wrote, “and Keeley presented what was styled a Gothic church.”

Sts. Peter and Paul Parish on 3rd Street became the first church attributed to Keely. Father Malone and the builder remained friends for the rest of their lives.

RELATED: Blueprints of Hope: The Story Behind Brooklyn’s Lost Cathedral

Although that church was demolished and replaced with the current building, according to Kervick, it “marked the beginning of a new epoch in Catholic architecture.”

“Keely,” he added, “was approached from all sides with requests for designs of churches and other necessary structures for an expanding religious life. On Long Island alone, there was a great wave of Catholic settlers for whom churches were urgently needed.

“Keely was the only one thought of to do the work.”

Many of the buildings still stand, each displaying Keely’s keen appreciation of Gothic-style churches with towering steeples, pointed arches, spires, and stained glass.

The Brooklyn portfolio includes St. Anthony of Padua in Greenpoint, Mary Star of the Sea in Carroll Gardens, and St. John the Baptist in Bedford-Stuyvesant. St. Charles Borromeo in Brooklyn Heights is known as a “milestone” for Keely, as it is his 325th completed church.

In his 1953 biography of Keely, Kervick wrote that Keely’s contemporaries had died, and although the architect and his wife, Sarah, had 17 children — some of whom also became architects — they, too, were gone.

Kervick, without survivors of Keely to interview, relied on his business letters to source the architect’s integrity.

One such memo was sent in 1849 to the Brooklyn-born prelate who would become the first cardinal in the U.S. — John McCloskey. At the time, he was the Bishop of Albany, but would later become the Archbishop of New York.

Keely wrote to Bishop McCloskey to defend himself against complaints from trustees of a new church upstate.

According to Kervick, Keely wrote: “I received your letter yesterday which makes me feel sorry that so many complaints are against me and in having you feel annoyed on account of me.”

He further wrote that he aimed to defend himself against the complaints, but if then-Bishop McCloskey was unmoved, he would resign and accept no pay for work already completed.

“If you give me nothing,” Kelly added, “I never will ask or trouble you for it.”

Ultimately, the future Cardinal McCloskey decided in favor of Keely, who went on to complete more work in Albany, such as the Immaculate Conception Cathedral in 1852.

Keely died at his home at 257 Clermont Ave. at age 80. He is among 1,500 New Yorkers who died of complications related to a massive heat wave in 1896.

Father Malone eulogized his friend of 50 years in a tribute republished in the book, “Diocese of Immigrants: The Brooklyn Catholic Experience, 1853-2003.”

The priest wrote that Keely was a man who “honored and served God as fervently as a priest or bishop at the altar.”

“He had genius, inspiration, and stimulus of Catholic principles and of the Catholic Faith deep down in his soul,” Father Malone further stated. “His was a great missionary work, and we would be unworthy of the Celtic race, unworthy of benediction, were we to allow the memory of such a man to perish.”

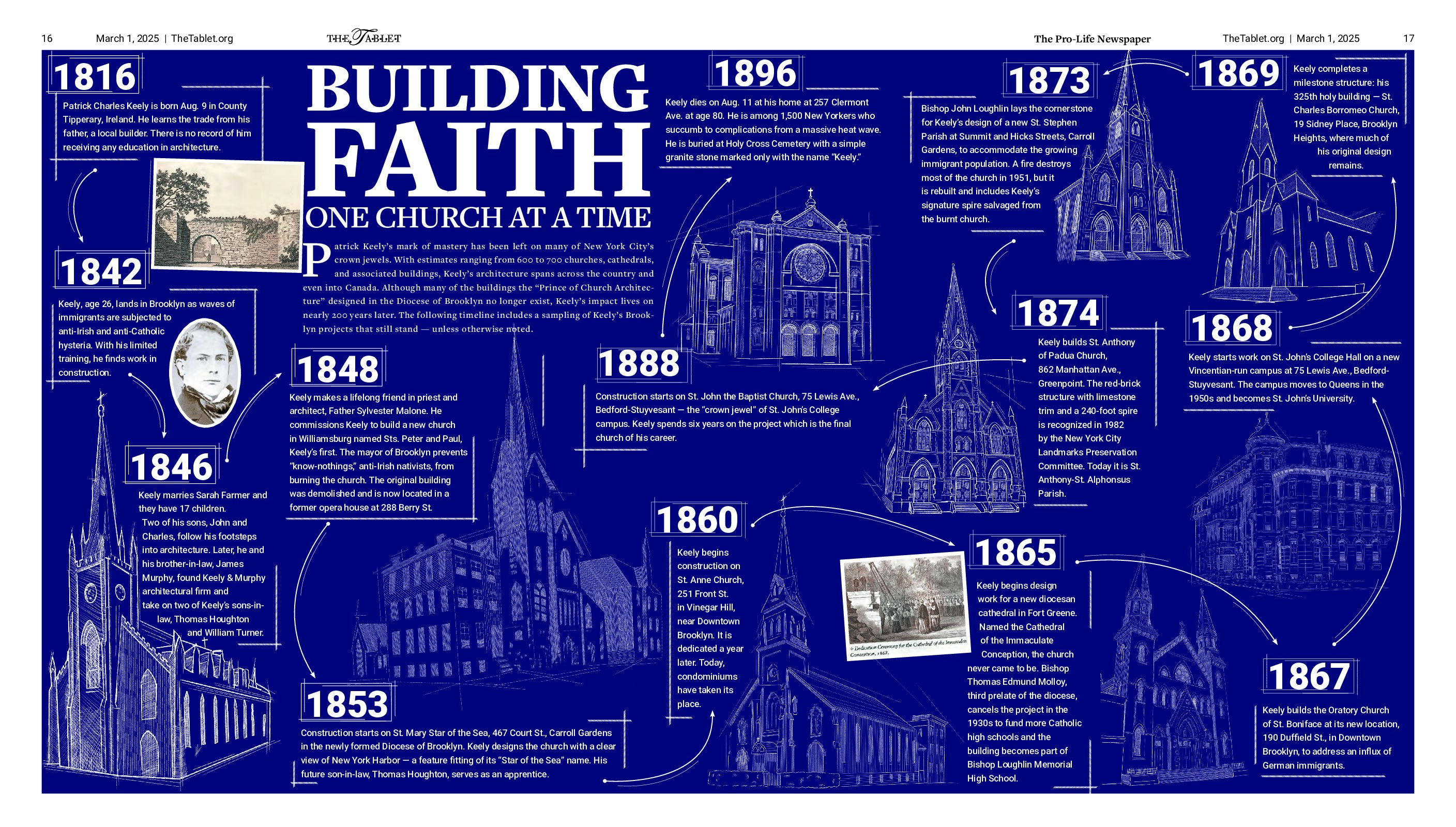

Click the image below to view the full PDF of centerfold of the March 1, 2025 printed edition of The Tablet, which follows the chronology of Patrick Keely’s architecture in the Diocese of Brooklyn.