PROSPECT HEIGHTS — If someone walks to the back of Division 10, Row 9, of Mount St. Mary Cemetery in Flushing, they’ll notice a unique grave marker bearing the Major League Baseball logo, and below it the sentence, “First among the vanguard of Latin Americans who changed Major League Baseball forever.”

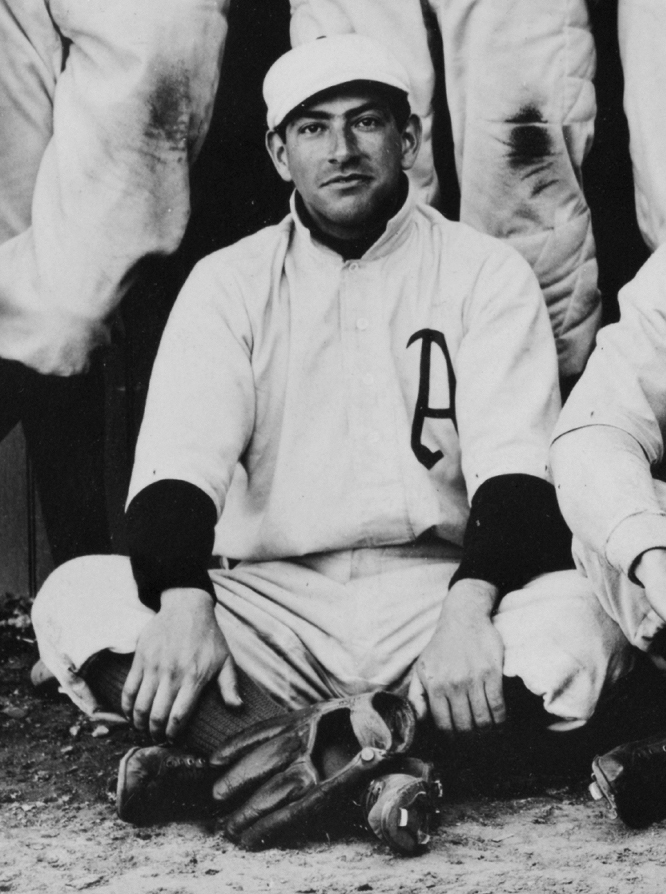

The gravemarker belongs to Luis Castro, who despite playing just one year in the majors in the early 20th century, changed the league’s trajectory forever as its first Latin-born player. Today, about 30% of major leaguers are Latin American.

Castro was born in Colombia on Nov. 25, 1876, and came to the United States, specifically New York City, in October 1885, when he was 8 years old. Fast forward to his young-adult years, Castro attended Manhattan College and played baseball but eventually dropped out to pursue the sport with a number of different semi-pro clubs.

Then, in 1902, when Castro was 25 years old, he was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics as a utility player, but ultimately became their starting second baseman when Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie left to play in the new American League for more money.

Lajoie, however, lost to the Athletics in a court battle over his move, and returned to the team the next year as its second baseman, ending Castro’s career.

Still, in that one year with Castro manning second base, the Athletics won the pennant. In 42 games, Castro’s batting average was .245. He had 35 hits, including eight doubles, a triple, and a homerun. In the field, he made 17 errors — 14 at second base, two in center field, and one at shortstop, according to the Baseball Almanac.

Beyond his on-field statistics, a biography of Castro written by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) describes him as “one of the largest personalities in the game” because of his “charm, geniality, and wit.”

“Few left his company without a smile on their face,” the biography reads.

After Castro left the Athletics, he bounced around with some semi-pro clubs for a handful of years. In 1906, Castro got a job as an undertaker in Birmingham, Alabama, and rumors began to swirl that he was retired.

The next year, he returned to the diamond for a club in Atlanta, who he played for the next two seasons, working still as an undertaker and mortician in the winter, according to the biography.

For the 1909 season, Castro accepted a position as a manager, and he then bounced around with teams in the South as a player-manager through 1914. He then got into some business ventures, and by 1930 was back living in Queens, according to SABR.

Castro died on Sept. 24, 1941, at the age of 64. For decades after his death, the grave was unmarked at Mount St. Mary’s. Then in 2019, newly elected New York State Senator Jessica Ramos — Colombian herself — having previously discovered Castro’s story, reached out to MLB about his grave, and his legacy as the league’s first Latin-born player.

MLB connected Ramos with SABR, who confirmed Castro was the first Latin-born MLB player. Then SABR, through its 19th Century Baseball Grave Marker Project, and in conjunction with MLB, got his gravemarker redone. It bears Castro’s full name, date of birth and date of death, the MLB logo, SABR logo, a cross, and the aforementioned sentence commemorating him as the league’s first Latin-born player.

Ramos recently told the Tablet that it was really important to honor Castro because he is an inspiration to younger generations of Colombians that they can forge their own paths.

“That was really important to me in celebrating our heritage as Colombian Americans and hopefully inspiring younger generations to pioneer initiatives and industries, and that the sky is the limit for us, too,” Ramos said.

MLB and SABR declined to comment for this story.

The remodeled gravemarker was unveiled in July 2021. At a ceremony at the cemetery, Ramos spoke about Castro’s life and legacy. She said that at the ceremony it was very emotional to see the community come together to honor Castro.

“I had been holding this story so dear for so long, and I would tell people about it when I spoke with them, but I don’t think that they actually understood the importance,” Ramos said. “And now I think with the marker and more people knowing his story, little by little, people will recognize his contributions.”