PROSPECT HEIGHTS — With the need for transparency cited as the predominant factor, a Baltimore court has ruled that almost all redacted names in a Maryland Attorney General’s report on child sex abuse in the Archdiocese of Baltimore can be revealed.

The decision concludes a long-running legal battle over the release of the redacted names, with survivors and advocates leading calls for disclosure. Initially, the stated reason for the redactions was to protect confidential grand jury materials, but the Baltimore court’s recent decision placed a greater importance on the need for a complete report on the scope and scale of the abuse crisis.

“As noted throughout this ‘Memorandum Opinion’ and the court’s earlier orders in this case, there is a particularized need to publish a report that is as transparent and open as possible,” concluded Baltimore Circuit Court Associate Judge Robert Taylor Jr.

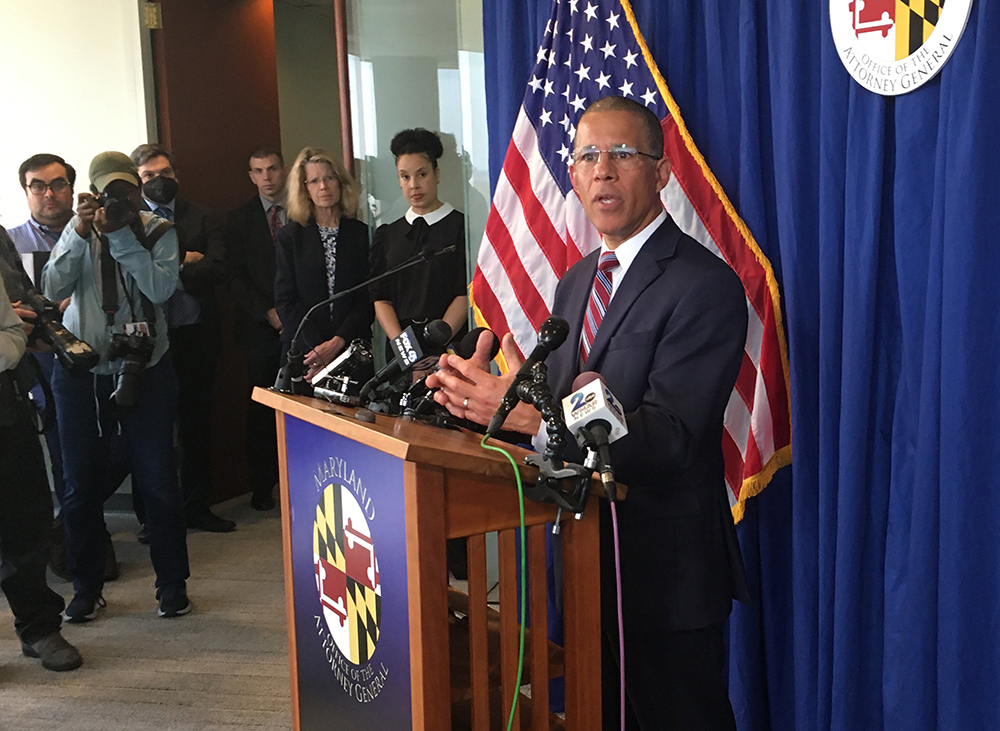

The “Memorandum Opinion” was issued Aug. 16 and released by Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown and the Archdiocese of Baltimore on Aug. 22. Brown also announced that his office will release a new, substantially unredacted version of the initial report around Sept. 26.

“The court’s order enables my office to continue to lift the veil of secrecy over decades of horrifying abuse suffered by the survivors,” Brown said in an Aug. 22 statement.

The archdiocese, meanwhile, said that its prayers are with the survivors of child sex abuse.

“Our foremost thought remains our concern and prayers for survivors of child sex abuse,” the archdiocese said in an Aug. 22 statement. “Today’s opinion will no doubt be a reminder for survivors and others of the great harm done to children.”

The initial report was published on April 5. Totaling 454 pages, it detailed more than 600 instances of child sex abuse by 156 abusers from the Archdiocese of Baltimore. According to the report, the majority of the abuse took place between the 1940s and 2002 — the year the U.S. bishops implemented the Dallas Charter, establishing a set of procedures dioceses must follow to address allegations of sexual abuse.

There were 46 names that were withheld in the initial report. The new version will reveal 44 of the 46 names, including 10 from the report’s list of abusers, and five archdiocesan officials.

In the months since the report was first published, all 10 of the names on the report’s list of abusers have been publicized, according to the “Memorandum of Opinion” — nine via the press, and one via a list of credibly accused that the archdiocese maintains on its website.

Back in May, as names began to trickle out in the press, Baltimore Archbishop William Lori pushed back, saying many of the news stories didn’t “provide a full or completely accurate picture” of the archdiocese’s decades long efforts to improve accountability and enforcement efforts. He also made it clear that “no one who has been credibly accused of child abuse is in ministry today or employed by the archdiocese.”

Within the “Memorandum of Opinion,” it is detailed how four of the 10 individuals whose names are redacted in the initial report’s list of abusers fought the revealing of their name in the new report. In essence, each one claims that the accusation(s) against them are false.

As for the other six, one has been added to the archdiocese’s list of credibly accused, four could not be located or did not respond to the renewed motion to publish their name, and one is deceased.

Brown argued they should all be identified “because a complete report of the scope and scale of the abuse crisis requires full transparency, because secrecy and nondisclosure helped create a lack of accountability which prevented meaningful, timely responses in the past, and because the continued anonymity of abusers and church officials simply confound the problem.”

As for the five archdiocesan officials whose names will come to light, Brown similarly argued the names should be revealed for transparency purposes. Some of those officials have argued that there are “inaccuracies or misleading insinuations” in the report, and therefore there is no public justice in publishing that information. The court ultimately sided, however, with Brown’s reasoning.

And as for the other 31 names redacted in the initial report, the court highlighted that even though most of them “played relatively minor roles” in abuses and coverups, it is still important to include their identities for transparency purposes.

Several of these individuals also opposed the publishing of their names, the court’s ruling states, for fear of “guilt by association.”

After a tumultuous few months since the release of the initial report and ensuing legal process, the archdiocese maintains that it “will continue to respect the process and actions of the courts,” and remains committed to maintaining a safe environment.

The archdiocese “has not opposed the release of the Attorney General’s report,” its statement said.

“We are committed to continuing all of our efforts to keep safe the children in our care, and we recognize that the Attorney General’s report is a reminder of a sad and deeply painful history tied to the tremendous harm caused to innocent children and young people by some ministers of the Church,” the archdiocese said.