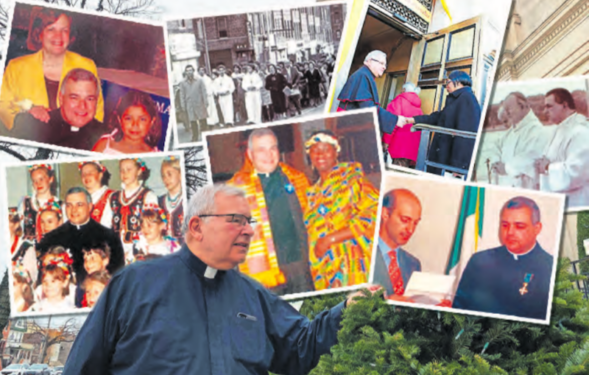

Pastor steps aside, but legacy of innovation endures for immigrants and a changing world

DYKER HEIGHTS — In Isaiah 56:7, the Lord says, “my house will be called a house of prayer for all nations.”

And so it is at St. Rosalia-Basilica of Regina Pacis Parish at the border of Bensonhurst and Dyker Heights. Here, Mass is celebrated each week in English, Italian, Mandarin, and Spanish.

Msgr. Ronald Marino grew up in a family of Italian heritage just a few blocks from the basilica. He recalls, as a little boy in the late 1940s, watching its construction.

He served most of his priesthood at Regina Pacis, including 16 years as pastor, overseeing dramatic growth of the congregation’s diverse cultural backgrounds. Under his leadership in 2012, the iconic house of worship received Vatican approval to be a minor basilica.

On Jan. 1, Msgr. Marino retired from administrative duties at the parish, but not from priestly work.

“I will have the title ‘pastor emeritus,’ ” he said with a soft-spoken demeanor. “But I will be helping out here, whenever they need help.”

With nearly 50 years as a priest, Msgr. Marino is also a lifelong resident of southeast Brooklyn, having grown up in Bensonhurt’s “Little Italy” enclave. He has observed enormous expansions of the neighboring Hispanic and Asian communities, and not just at his parish.

Until 2018, he was the episcopal vicar for ethnic and migrant apostolates for the Diocese of Brooklyn. He fought for immigrants’ rights and causes, and he testified about those issues before government panels.

He has collaborated with Bishop Emeritus Nicholas DiMarzio on immigrant issues since the mid 1980s. At that time, the now-retired bishop was a monsignor directing the Office of Migration and Refugee Services at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) in Washington D.C.

“I do go way back with him,” said Bishop DiMarzio, who retired Nov. 30. “I’ve seen him obviously stay with the issues so well, and really be somebody you could go to and get a view on the ground level of what was happening. Then becoming pastor there at Regina Pacis, and having it become a basilica, I think is a tribute to his ingenuity. So, I really do thank him for his wonderful ministry.”

Ironically, Msgr. Marino, ordained in 1973, was apprehensive when first tasked to help immigrants.

Msgr. Anthony Bevilacqua, the future cardinal and archbishop of Philadelphia, requested that the young priest join him at the migration office that he created for the Diocese of Brooklyn in 1971.

It began as a part-time job, because Msgr. Marino was still at his first assignment as a parish priest at Our Lady of Grace in Gravesend.

“I said to him, ‘But I don’t know anything about immigrants,’ ” Msgr. Marino recalled. “He said, ‘The immigrants themselves will teach you everything you need to know.’ And that was true.”

Msgr. Marino said he did not understand why he got picked for the job, considering his misgivings and because he was an inexperienced young priest. But now he understands.

“It was the Holy Spirit,” he said, “because the Holy Spirit guides everybody to do the work he wants done. I believe that to this day.”

Subsequently, Msgr. Marino plunged into migration issues, including a massive effort to help newcomers to the U.S. via the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986.

That legislation covered many issues and officially outlawed businesses from knowingly giving work to undocumented immigrants. But it also legalized nearly 4 million undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. before 1982.

Bishop DiMarzio worked on this “amnesty” program for the USCCB.

“Many of them had already been here for years,” he said of the amnesty recipients. “Brooklyn was a big area. It always has been, and will be, the landing place for most of the immigrants.”

‘We Processed Thousands’

Notably, amnesty seekers had to show that they were working, that they could support themselves, and had access to benefits, Bishop DiMarzio pointed out.

Msgr. Marino got busy developing a system to help immigrants gather documentation proving they qualified for amnesty.

“There were many undocumented people here in 1986,” he said. Diocesan efforts to assist the processing of those people were successful. “Here in Brooklyn, we had the second largest number of processed immigrants in the amnesty program. Number one was Los Angeles.”

At the time, information technology was rapidly improving, but the diocese’s computers were largely used for word processing, Msgr. Marino said. Therefore, he relied on specially trained volunteers in each parish to help applicants gather their paperwork and rehearse the interview process conducted by government immigration officials.

“I wanted this to be a parish thing,” he said, “so that the people would know that the Church did it for them, not the government.”

Bishop DiMarzio said implementing the amnesty policy was important for the U.S. and for the Diocese of Brooklyn.

“It gave them status,” he said of immigrants who were granted amnesty. “They felt they were really part of the culture now and could participate, especially in the life of the Church.”

Msgr. Marino said the amnesty work was “a very proud moment for the Church.”

He recalled recently visiting one of his favorite restaurants in Bay Ridge, where two of the waiters are longtime friends from when the diocese helped them achieve amnesty. Both are Muslim — one from Albania, the other from Egypt.

Until the Resurrection

In recent years, Msgr. Marino focused on the needs of immigrants at Regina Pacis.

Last spring, the parish added a second Sunday Mass in Spanish for the rapidly growing Hispanic community.

Meanwhile, the parish’s Asian population has also grown; when Msgr. Marino became pastor, there were fewer than 10 Mandarin-speaking parishioners; now there are more than 100.

To better serve both groups, Msgr. Marino recruited parochial vicars fluent in those languages.

Father Joseph Lin leads the Chinese ministry, while Father Gesson Agenis celebrates Mass in Spanish. Father Sebastian Tarcisio Andro, who became parish administrator after Msgr. Marino retired, speaks fluent Italian and Spanish.

Under Msgr. Marino’s leadership at Regina Pacis, the parish’s finances were stabilized. A columbarium was established in the basilica’s undercroft; its burial niches are an important source of income for the parish. Since the basilica can’t be shuttered, the niches are permanent, and there is room for many more, with income to follow.

There are 189 people interred there now, and about 100 more have been pre-purchased. But the chapel has room for 3,000.

“We can do this because we’re a basilica,” Msgr. Marino said. “A basilica cannot be closed by the diocesan bishop — it is part of the Vatican … So with that, we promise forever — until the Resurrection.”