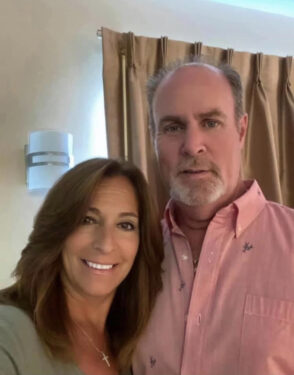

BATH BEACH — Chris Sorrentino was in lower Manhattan on his way to work at the New York Stock Exchange on the morning of the terror attack when everything changed.

He still has a hard time thinking about that day. But Sept. 11 never goes away for another reason: the toxic dust at ground zero that he breathed in over the next several months and the bladder cancer he developed years later.

Tens of thousands of first responders and people who lived or worked in lower Manhattan breathed in air filled with the toxic dust from the collapse of the twin towers. Many, like Sorrentino, were diagnosed with cancer or other illnesses and are having all or part of their medical expenses covered by the World Trade Center Health Program.

Sorrentino, who lives in Bath Beach and is a longtime parishioner of Most Precious Blood Church, is haunted by his memories.

“I saw the second plane. I said to myself, ‘My God, that plane is flying low.’ Then it hit the tower. I was able to see the explosion. I heard the building collapse. There was a cloud of dust. People were running down the street. I was covered from head to toe with dust,” Sorrentino recalled.

“It was a horror,” he said.

With the subways shut down, Sorrentino made it home to Brooklyn thanks to his wife Patricia. Despite being an inexperienced sailor, she pulled up anchor on the couple’s boat in Gravesend Bay, and piloted it to Lower Manhattan, where she picked up her husband and several other people — many of them strangers — and whisked them away.

Chris Sorrentino returned to his job on the floor of the Stock Exchange a week later. He worked there for the next four years, leaving in 2005 to take a job as a maintenance engineer at a hotel.

In 2018, Sorrentino was diagnosed with a rare form of bladder cancer. “It was a challenge,” he said, adding he was often in excruciating pain.

He endured a painful biopsy with no anesthesia and then underwent an operation in which Dr. Gary D. Steinberg, a urologic oncologist at NYU Langone, removed his bladder.

“It just goes to show you, you can get sick years later. I’m an example of that,” he said.

“More people have died from 9/11 illnesses in the last 20 years than the nearly 3,000 people who perished on that horrible day,” said attorney Michael Barasch, a partner in Barasch & McGarry, the law firm representing Sorrentino.

“This toxic dust didn’t care whether you were a Democrat or Republican, black or white, Catholic or Jewish. It affected everyone,” Barasch said.

As of June, 81,460 first responders and 30,582 others who lived or worked near the twin towers have enrolled in the WTC Health Program, which provides health care and monitoring to survivors.

The program was established through the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act, a federal law Congress passed in 2010. It is named in memory of NYPD Det. James Zadroga, who had worked in the recovery effort at Ground Zero in the months after 9/11 and died in 2006 of respiratory disease.

In addition to first responders, there were an estimated 300,000 office workers, 50,000 students and teachers, and 25,000 residents living south of Canal Street breathing the same air, Barasch said.

“The sad reality is that only 8% of the non-first responders have enrolled [in the WTC Health Program] because they simply don’t realize that they are entitled to the same free health care and compensation for the same illnesses,” he said.

Sorrentino said that after his operation, he faced $400,000 in medical expenses. The health program paid $280,000 toward his bills. He also qualified for a financial aid program at NYU Langone and worked out a payment plan for the rest.

The mental anguish is still there. Each year, the 9/11 anniversary is a tough time for him. “For a week leading up to the anniversary, I’m a basket case,” he said. “I do my best to live with it.”