By Father John Gribowich

PARK SLOPE — Pope Francis, addressing the U.S. Congress in 2015, spoke of four exceptional Americans to be emulated during our challenging times.

There was a certain irony in the Pope praising Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton, both Catholics, to a group of elected officials. Neither of them ever intentionally exercised their right to vote.

For Day, arguably one of the most politically charged Catholic activists of the 20th century, the radical change she desired in American society could never be brought about through the so-called democratic process.

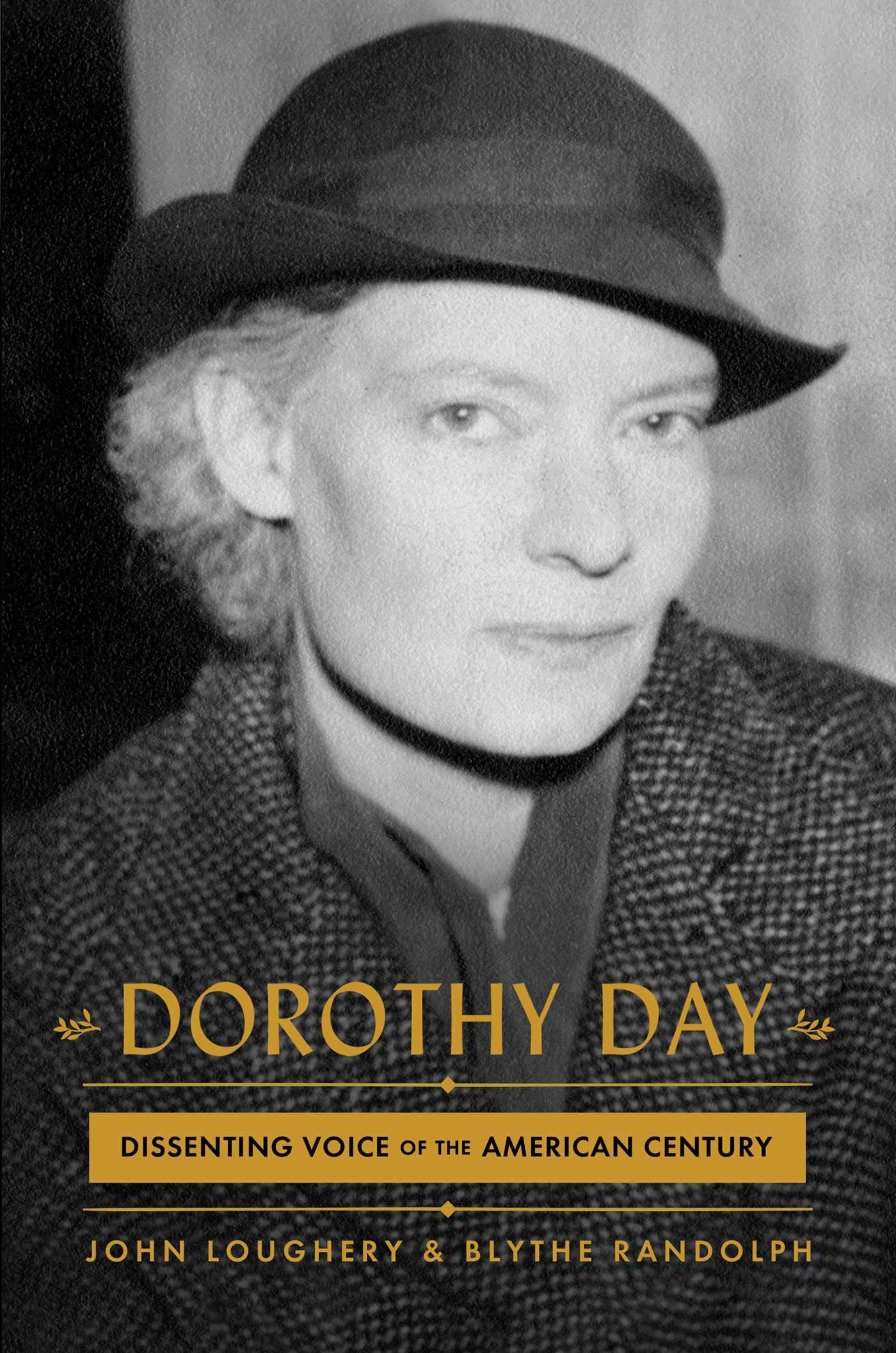

This controversial stance and many others are unpacked in John Loughery and Blythe Randolph’s “Dorothy Day — Dissenting Voice of the American Century,” the latest biography of this mystifying woman who is on the road to sainthood.

The complexities of Dorothy Day’s life and public advocacy are so unique that it is difficult for a biographer to fully, let alone enthusiastically, embrace her complete “project.”

Traditionally minded writers empathize Day’s love of liturgy, the sacramental life, and the dogmas and doctrines of the Church — especially as they pertained to sexual morality. While progressive writers highlight her support of labor unions, direct action to the poor, and involvement in the civil rights and anti-war movements while relegating her Catholic piety as a parochial product of her age.

Loughery and Randolph do a fine job vividly bringing to life all the complexities of Day’s unique life, but it is clear that they are more sympathetic to her “progressive” side than her “dogmatic” one. That being said, there is much to be gained by a reading of “Dissenting Voice…”

The authors do a thorough job telling the story of Dorothy’s wild “pre-Catholic” adventures, her tumultuous love affairs, and the momentous birth of her daughter Tamar. One can rightly conclude that Dorothy became a Catholic not despite these experiences, but in many ways because of them.

Her constant pursuit of the good — as varied and unconventional as they might be — was her pursuit of Christ, the source of Goodness.

“Dissenting Voice…” also does an excellent job in highlighting tortuous Dorothy’s commitment to pacifism — a position that she formulated well before she became a Catholic.

How could she be against eliminating the inhumane aggression of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin — all who unapologetically killed millions of innocent people? Likewise, her uncompromising position on birth control was a stumbling block for those who advocated woman’s liberation.

Day’s backing of traditional sexual morality seemed inconsistent with her criticism of the Church hierarchy for neglecting issues of social justice. Where “Dissenting Voice…” falls short is showing the relationship between these two positions.

Despite her incessant activity well into her seventies and early eighties, Day was fundamentally a contemplative who unknowingly and later knowingly desired heaven. Yet for her heaven was not simply a reward for a life well lived on earth, it was a reality that was meant to be lived in the here and now.

She contemplated the heavenly presence of Christ in each person that she meant. Her pacifism was rooted in the reality that in heaven there is no violence or war. She embraced the sexual teachings of the Church because she was convinced that desiring a union with God could ultimately purify and transcend sexual desires.

In short, what made Day a radical was that her beliefs were rooted in the Word from heaven who became flesh on earth.