Where Have All the Convents Gone?

This is the sixth in a series about how former convents are being used in Brooklyn and Queens.

At the turn of the century, when faced with a crumbling and stripped-down former convent building at All Saints, Williamsburg, then-pastor Father Donald Kenna, could have shown interest in the proposal to convert the property into a fitness center.

It seemed like a lucrative deal at the time, said William Ortiz, who served as the minister of temporalities at the parish during that period. But Father Kenna would hear none of it. A fitness center is not the kind of service he had in mind for the community.

The situation was becoming dire. Although originally a convent building, 115 Throop Ave. has served varied populations. After the sisters moved out, the city used it as a site for its TAP Program in the 1970s. The program was an effort to help youth find summer employment.

After TAP moved out in 1989, Father Peter Young led the Altima Program in the building. With limited funding, the program helped men adjust to life after prison. It had a 98-percent success rate, measured by how many men did not return to prison.

Altima closed in 1998 and the building stood unoccupied for over two years.

“People started coming in, stealing pipes, taking anything they could sell from the building,” Ortiz said.

Then Father Jim O’Shea, C.P., got a nun to look at the space.

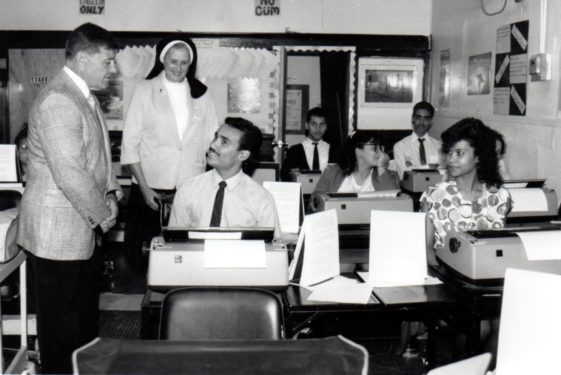

Sister Mary Franciscus, R.S.M., ran Opportunities for a Better Tomorrow (OBT) in Sunset Park. She founded the organization in 1983 to help at-risk, out-of-school and unemployed youth get job ready. Fifteen years later, she was ready to expand, and Williamsburg had the population she was targeting.

“When Father O’Shea showed her the building, she fell in love with it,” Ortiz said. She could see past the broken windows, the lack of pipes and wreck of it all.

From Eyesore to Open Space

Sister Mary decided the building was exactly what she was looking for and poured investment money into it. The Diocese of Brooklyn, the parish and OBT worked out a 10-year lease. And then OBT transformed the building – from an abandoned eyesore that still had small cells the sisters used – into an open space where young people could feel like they were walking into a professional corporation.

The building is located on a highly trafficked street, making it accessible and easily identifiable to locals. Nonetheless, in order for OBT to be successful, they had to get the community on board. To help with that process, OBT hired Ortiz as an assistant program director. He had the local knowledge to help OBT ground its roots. They did outreach directly to the community, went to the community board and made their rounds around community centers. Eventually, word of mouth took hold and the center was filled with youth trying to get a head start on their careers.

Ortiz, who is now site administrator for OBT, said he remembers that first class in 2001. He has fond memories of one particular young man who was kicked out of the program twice before he finally got his head in the game. Now that young man, Ortiz said, brimming with pride, must be earning at least twice as much as Ortiz in his job as a banker.

OBT offers high school equivalency, medical administration and internship programs. Students get help developing computer and interview skills. They also receive educational and financial aid to get to college.

Strive to Change Perceptions

However, the most important thing the center does is to change the youths’ perception, said Frank Mitchell, director of justice programs.

Mitchell is a former gang member that now helps youth get situated on a good professional path. He said that whenever anyone new comes into the program, he or she is looked at as an individual, taking into account his or her personal and family history, ambitions and personality. Then a program is individually designed to benefit the new student.

He said one of the most important things he tries to instill in the young people is “code switching.” He does not ask the young people to completely change who they are, he simply asks them to turn on their “professional mode” when they come into the building.

Strict, But Fair

Being professional is strictly enforced at OBT. Students have a dress code, most have to clock in and out, and they are given a daily stipend.

Mitchell said it all comes from what Sister Mary used to always say: “It’s not enough for us to see the good in them; they have to see the good in themselves.”

“They don’t just see you as a student,” said 18-year-old Alexis Diaz. “They see you as a person.”

This manifests itself in the small things, Diaz said, such as being greeted at the door and being noticed when hungry.

He said the program can be tough. The dress code is enforced to the smallest detail, he said, but its worth it. He wants to go to college.

Although All Saints parish is not involved in the activities of OBT, Father William Chacón, a recent pastor, said they are good tenants.

“We support each other,” Father Chacón said. “We are working for the good of the community.”

I met Sister Mary Franciscus when I worked for a city agency that helped fund OBT. Sister was an extraordinary woman who pulled together programs that truly made a difference. She was smart, caring and compassionate; when I broke an ankle, she would call with advice based on having broken an arm…when I lost a brother on 9/11, she understood the enormity of my loss because she too had lost a brother. Thank you for this article which brought back so many good memories of this wonderful woman.