ASTORIA — At age 98, Bill LaCovara has to slide gradually from his easy chair, but once standing, he smiles broadly and delivers a firm handshake.

Leaning on a cane, he apologizes for rising up so slowly, but proudly adds, “I still got my faculties.” That’s an understatement.

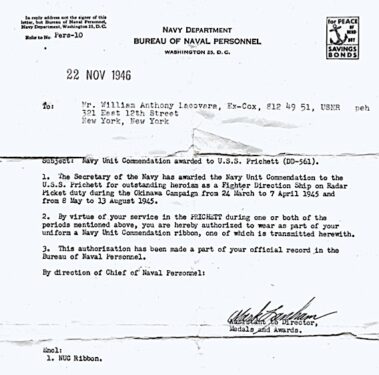

With no difficulty at all, LaCovara rattles off names, dates, and places of every major naval engagement in the Pacific during the last two years of World War II. He was there, serving aboard two destroyers — the USS Wadleigh and the USS Prichett.

Seaman 1st Class LaCovara — later a boatswain’s mate — fought at sea in the Marshall Islands campaign, the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the first naval raids on Japan, the invasions to retake the Philippines, the attack on Iwo Jima, and, finally, Okinawa.

On June 14, the Knights of Columbus, Council 11449, at LaCovara’s parish, Immaculate Conception in Astoria, honored him at the organization’s annual flag-raising ceremony. The venue was the parish’s Catholic academy, and students from the school participated in the ceremony.

“I’m a little nervous about it,” LaCovara told The Tablet before the event. “But don’t get me wrong. It’s an honor. I’m the oldest Catholic War Veteran from Immaculate Conception; maybe the oldest one in Astoria.”

You Never Know

LaCovara’s countenance beams as he describes his late wife, Carmelita, and their two children, Margaret and Mike. He has two grandchildren — Mike’s sons — now young adults. LaCovara calls them “two beautiful boys.”

The family embraced parish life at Immaculate Conception. LaCovara proudly describes the opportunities and friendships he had, filling many roles, like organizing the ushers.

His mannerisms are quintessential Italian-American, with hands waving and expressions like, “What are you gonna do?” But his mood shifts to stark solemnity while recalling the war.

Soberly, he offers another understatement: “That is not an easy thing — to fight an enemy. You never know how it’s going to turn out.”

Carnage at Sea

U.S. Marines and soldiers faced determined Japanese defenders in bloody “island-hopping” campaigns from Guadalcanal to Okinawa.

Still, the carnage in the Pacific Theater was not confined to ground fighting.

Japanese ferocity intensified as U.S. forces advanced. LaCovara and his shipmates endured multiple waves of bomb-laden aircraft flown by suicide pilots — the kamikazes.

The Wadleigh and the Prichett took major hits, as did LaCovara himself, sustaining shrapnel wounds to his right leg and scalp.

By his count, 12 destroyers were sunk, 11 by suicide planes, in the Okinawa Campaign alone.

“I saw a lot of men get killed,” he said. “I saw that for 20 months in the Pacific.”

First Diploma, Then Navy

LaCovara was born on Nov. 28, 1924 (Thanksgiving Day), on East 12th Street in Manhattan. He grew up there, the youngest of three children.

His siblings, Nancy and Vic, were twins and three years older than him.

Their mother, Margaret, was born in the U.S., but their father, Dominic, came to the U.S. from Italy in 1909. During World War I, he joined the American Army and was wounded and gassed in France.

Years later, LaCovara’s father warned him not to be an infantryman and face trench warfare as he did.

So LaCovara enlisted in the Navy In January 1943. But he was still a senior at Textile High School in Manhattan.

So LaCovara enlisted in the Navy In January 1943. But he was still a senior at Textile High School in Manhattan.

He thought he’d drop out to start military training like other enlistees. But his homeroom teacher, Mrs. Tierney, and the principal, Mrs. Osgood, believed he should graduate first.

LaCovara said he was annoyed when they arranged a deferment for him. But he got his diploma in June and entered the Navy a month later. Now he appreciates what the educators did.

As sharp as he is, LaCovara can’t remember their first names. But he fondly recalls how Mrs. Tierney sent him care packages while he was at sea.

Enter the Pacific

LaCovara was a Seaman 1st class deckhand when he boarded the Wadleigh in October 1943.

The destroyer sailed for North Africa to help escort the battleship USS Iowa back to the U.S. The Iowa was ferrying President Franklin Roosevelt home from the landmark Tehran conference with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin.

Later, the Wadleigh moved through the Panama Canal to join the Pacific Fleet.

Through the winter and spring of 1944, LaCovara served during the liberation of the Marshall Islands and the campaign to take the Mariana and Palau Islands.

In June, the Wadleigh launched depth charges to sink a Japanese submarine west of Tinian. LaCovara said the crew cheered when debris and dead Japanese sailors came to the surface.

A Pathetic Thing

LaCovara said he witnessed “a pathetic thing” offshore the island of Saipan.

“The Japanese told the civilian population that our Marines were coming to rape and beat them,” he said. “They were afraid.”

Standing on the Wadleigh’s deck, LaCovara saw civilians, some holding children, jump from a high cliff to their deaths.

An interpreter grabbed a megaphone and frantically urged the people not to jump, but it was futile. LaCovara heard a thud as each person hit the water. “The lagoon was full of bodies,” he said.

The people undoubtedly thought they were avoiding atrocities, but the opposite was true.

LaCovara said civilians who didn’t jump were shocked when the Marines offered supplies and medical care. “Of course, they gave the kids chocolate, food, and everything else,” LaCovara said.

On Sept. 16, LaCovara was taking a shower when the Wadleigh violently quaked with the explosion of a Japanese mine.

He hurriedly dressed, but shrapnel tore his right leg. Still, he leaped to the deck of another destroyer that pulled alongside to rescue the crew.

The Wadleigh’s watertight compartments kept it afloat, but the destroyer needed extensive repairs. LaCovara subsequently got orders to join the crew of the Prichett.

Gung Ho No More

The Prichett’s guns covered the U.S. amphibious landings in the Philippines and at Iwo Jima. They also struck Japanese positions in harbors on Formosa (Taiwan), Indochina (Vietnam), and Japan itself.

Next came “Radar Picket Duty” during the Battle of Okinawa in the spring and summer of 1945.

The island’s proximity to the Japanese mainland, about 400 miles, resulted in a fierce Japanese defense and the bloodiest fighting of the Pacific Theater — land and sea. Suicide attacks accelerated. LaCovara recalled once seeing a dozen kamikaze planes in the sky.

“Okinawa changed everything,” he said. “I was ‘gung ho’ until then. I was scared like everybody else. And if they tell you they weren’t scared, they’d be lying.

“Because you never know when you’ll be hit by a suicide plane. During the daytime, it was beautiful, but at night, everything opened up.”

Kamikaze Miracle

On April 4, a 500-pound bomb hit the Prichett near a rack of depth charges.

“Nobody got hurt, but there was a big fire,” LaCovara said. “Then a miracle happened. I say a miracle because it’s unbelievable. Radar picked up a heavy squall (storm).

“The Prichett went into it, and the rain put out the fire. In the meantime, from the squall, you could see the Japanese dropping flares, looking for us. They probably thought they’d sunk us, but they couldn’t find us.

“We did a lot of prayer.”

Cracked in Half

The Prichett was repaired, and in July it returned to the waters near Okinawa, a string of tiny islands south of the Japanese mainland.

A fellow destroyer, the USS Callaghan, was hit starboard by a low-flying kamikaze. The plane pierced the engine room and sparked a fire that spread to the ammo supply.

“The ship exploded, cracked in half, and it sank,” LaCovara said.

The Callaghan was the last U.S. ship of the war lost in a kamikaze attack, and 47 of its 300 crew members died.

But the Prichett was still in danger.

“We started to pick up survivors,” LaCovara said. “But, from a distance, you could see another plane coming in.”

Gunners missed the aircraft, which crashed into the ship’s superstructure, LaCovara said.

“That’s in the middle of the ship,” he explained. “There was a big explosion. A couple guys got killed, including a guy ripped to shreds. But the death toll wasn’t higher because a lot of guys ran. I had 10 guys on top of me, including my division officer.”

Although damaged, the Prichett kept rescuing the Callaghan’s survivors. But the ship needed another round of repairs, so it journeyed home in August 1945.

The war officially ended on Sept. 2.

Many Roles

Weeks later, LaCovara walked up 12th Street to his parents’ home. His sister, Nancy, saw him from a window, ran outside, and jumped into his arms.

LaCovara became a printer, and in 1952, he married Carmelita at Immaculate Conception in Astoria, her home parish.

He has been a member since and filled many roles, from the Knights of Columbus to the St. Vincent de Paul Society, and the Catholic War Veterans, USA.

“I loved what I was doing,” he said. “I was president of the Usher’s Society. I counted the collections from Sunday for 26 years.”

LaCovara and his wife raised Margaret and Mike at their home in Astoria. Carmelita died five years ago.

“She had Parkinson’s,” LaCovara said. “It’s a tough disease. I wish she was still here, but what are you gonna do?”

You’d Be Surprised

LaCovara tries to forget the war, but sometimes it drifts back to him.

“I never talked about it,” he said. “What are you going to say? No, I figured what’s done is done. It’s all behind me.

“But you’d be surprised.”

If he allows it, his mind wanders through images of the doomed civilians on Saipan, the Callaghan’s fate, and losing shipmates — it’s all part of a life that’s spanned nearly a century. But LaCovara doesn’t worry about whether he’ll reach his 100th birthday.

“Everything is up to the Lord,” he said. “He’s the boss up there. He made it so I survived a war, and here I am. I’m still around, thank God.”

Another great article. Our greatest generation is slowly dying off. I have a 102 WWII friend who still lives alone and is doing quite well but does not want any publicity or fanfare. He was a bomber pilot over Germany! Previous articles talked about deceased heroes. Bill LaCovara is still with us! God bless him and all who served our country! Freedom is not free!