JAMAICA — Some biologists estimate that by the mid-1700s, New York Harbor held one-half of Earth’s oysters — a rich environment for one man to build a fortune as New York City’s “Oyster King.”

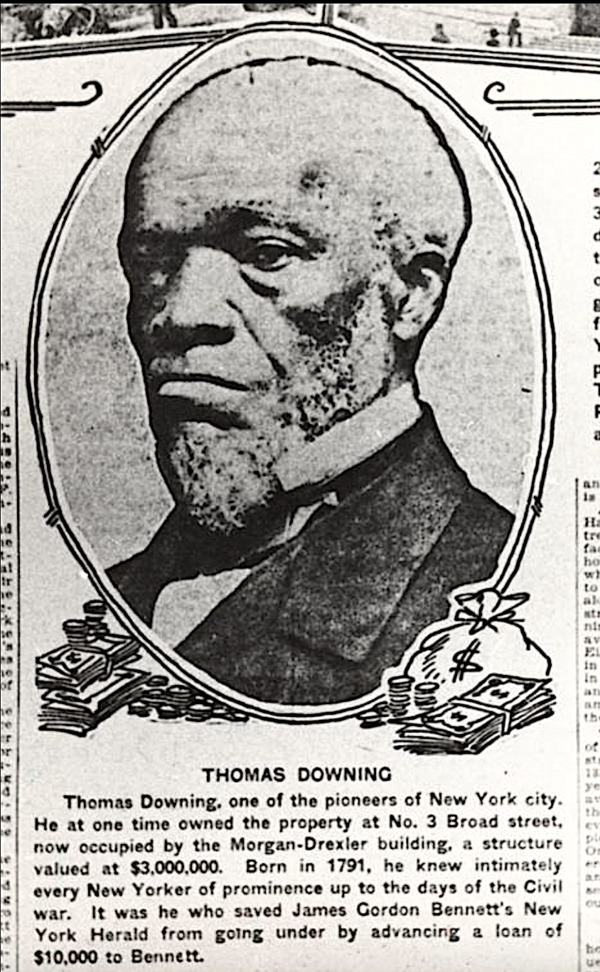

Thomas Downing — a freeman born to formerly enslaved people in Virginia — became one of the city’s wealthiest citizens as the proprietor of his world-famous oyster restaurant in Lower Manhattan.

Still, he risked losing fortune and fame by offering the basement as a stop for fugitive slaves destined for freedom on the secret “Underground Railroad.”

Downing’s other contributions, however, were anything but covert. He was a prominent member of abolitionist groups like the New York City Anti-Slavery Society and helped fund a high school and two elementary schools for black children.

Downing’s son, George, a famous abolitionist, was the subject of a 1910 biography by S.A.M. Washington. The author highlighted the similarities between father and son, writing that George had a “commanding figure and kingly bearing” and “aggressive temperament and manly character.”

Refined Tastes

Thomas Downing was born in 1791 on Chincoteague Island near the eastern shore of Virginia. His parents were slaves of a wealthy mariner, Capt. John Downing.

He freed them in 1783 upon learning that his new faith, Methodism (a Protestant-Christian denomination), condemned slavery.

As was the custom, Downing’s parents took their former master’s surname.

The sea captain also provided a tutor for their son, Thomas, which allowed him to receive an education and provided exposure to the refined tastes of the captain’s affluent dinner guests.

Meanwhile, the marine habitat surrounding Chincoteague Island was an excellent classroom for Downing to learn oystering.

Downing was 21 at the start of the War of 1812. He marched north with the U.S. Army to Philadelphia, where he met his future wife, Rebecca West. They had four sons — the eldest of whom was George — and a daughter.

In 1819, they moved to New York City to explore its thriving oyster industry.

Raw, Fried, or Stewed

African Americans, like the Indigenous people on the East Coast, thrived on oysters during that time, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The museum, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution, has a website describing how black sailors fetched oysters and how black vendors peddled them on city streets, serving them “raw, fried, or stewed.”

On Feb. 1, families visiting the King Manor Museum in Jamaica, Queens, experienced Downing’s legacy through an immersive program about black oystermen. Kids crowded over tubs of water to see and touch oyster shells in a simulated habitat.

It was a fitting venue for a program during Black History Month. The museum was the estate of founding father Rufus King, a signer of the U.S. Constitution, one of the first New York state senators, and a longtime opponent of slavery.

Little Oyster & Great Oyster Islands

About 30 years before Downing’s birth, the Hudson River’s estuary held about 350 square miles of oyster beds, according to author Mark Kurlansky’s 2007 book, “The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell.”

These beds, Kurlansky wrote, were found along the shores of Brooklyn and Queens, in Jamaica Bay, in the East River, and “all shores of Manhattan.” Kurlansky also noted that the earlier Dutch colonists “called Ellis Island and Liberty Little Oyster Island and Great Oyster Island because of the sprawling natural oyster beds that surrounded them.”

“According to the estimates of some biologists,” he added, “New York Harbor contained fully, half of the world’s oysters.”

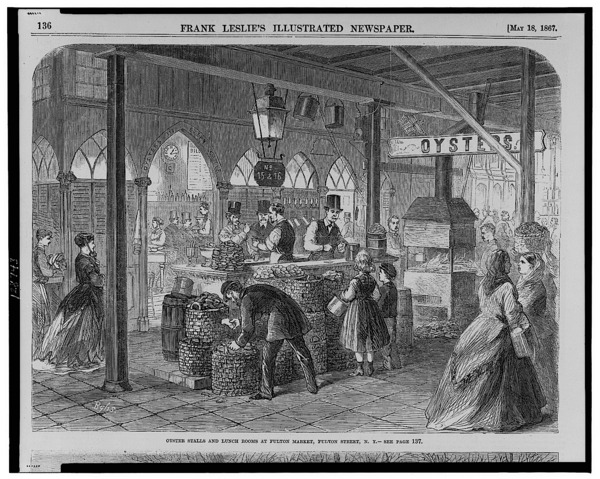

The Downings arrived in New York during booming sales for oysters sold on the street from carts or in raucous basement eateries known as “oyster cellars.”

Downing rowed the estuaries of New York Harbor in the early-to-mid 1800s. From his skiff, he “dredged,” “clutched,” or “tonged” for oysters, or he would pull alongside other boats and offer to buy the best of their hauls.

He prospered and set his sights on opening the City’s best oyster restaurant.

Fine Dining, Culture & Class

Oyster cellars were known venues of debauchery where the only female customers tended to be prostitutes, Kurlansky wrote.

Downing chose a different business model when he opened his restaurant in 1825. He selected a fine décor of chandeliers and expensive carpeting that invited family dining.

His famous restaurant, Downing’s Oyster House, was at the corner of Broad and Wall Streets in Lower Manhattan. It was a go-to spot for local captains of industry, politicians, and tourists, including the English author Charles Dickens.

The “Oyster King” moniker honored Downing for his reputation as an erudite embodiment of fine dining, culture, and class.

“Downing,” Kurlansky noted, “made oyster cellars respectable.”

Joined the Struggle

Downing’s family worshiped at St. Philip’s Church, founded in 1809 in Lower Manhattan. Now located in Harlem, it is the City’s oldest black Episcopal parish.

Its congregation has included the leaders W.E.B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, and Langston Hughes. The Downings’ pastor was the outspoken abolitionist Rev. Peter Williams Jr.

The restaurateur no doubt heard impassioned oratory from the pulpit that slavery gravely offended Christian values of human dignity. Downing, however, had already joined the struggle.

Although New York outlawed slavery in 1827, the institution persisted in southern states. So, Downing and other Underground Railroad “agents” kept helping escapees move north to Canada.

As the City’s elite dined in his restaurant, southern slaves hid in the basement, awaiting the next leg of their covert journey. According to Washington, as a teenager, George Downing famously met an escaped slave, “Little Henry,” and helped him avoid capture on his trek.

Risked it All

Although freed, Downing still suffered indignity. Despite his social status, he spent virtually his entire life as a non-citizen of the United States.

That finally changed the day before he died in 1866 when Congress passed a law affirming citizenship and civil rights for all people born in the United States, including those of African descent.

Meanwhile, until 1864, the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed “commissioners” to catch suspected escapees and return them to owners. Helping escapees could bring a $1,000 fine, six months in jail, and possible treason charges.

Etta Waddell of Brooklyn, who participated in the Feb. 1 program at King Manor Museum, said Downing surely knew the risks if caught hiding escapees.

“He would have lost his business, and he probably would have done time as well, even though he was friends with a lot of the elite people during that time,” Waddell said. “Just having the wherewithal to open an establishment and cater to the elite while helping his people — yeah, that was really commendable.”