by Father Robert Lauder

AS A NEW YEAR’S gift Father Joe Kelly gave me small paperback book. Father Kelly is a New York Archdiocesan priest who is now assigned as a spiritual director for seminarians in residence at Douglaston.

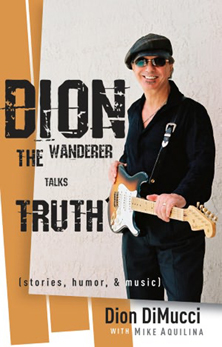

More than 35 years ago when he was a seminarian, he took some of my philosophy courses. When he gave me the gift I was grateful, though looking at its cover, I immediately thought this would never be a book that I would choose for myself. The book was Dion the Wanderer Talks Truth (stories, humor & music) (Cincinnati, Ohio: St. Anthony’s Messenger Press, 2011, pp. 146, $16.99). The book was written by Dion DiMucci and Mike Aquilina.

Though I knew Dion was a singer, I did not remember ever hearing him sing and I had absolutely no idea of his life. Though I am swamped by the amount of reading that I have to do for my philosophy courses at St. John’s University, I decided to read at least some of the book because it was a gift from Father Kelly.

What a great surprise the book turned out to be. Once I started reading I could hardly put it down. Dion captured my attention and interest early in his story and I became more interested the more I read. In his Introduction, Dion writes the following:

What a great surprise the book turned out to be. Once I started reading I could hardly put it down. Dion captured my attention and interest early in his story and I became more interested the more I read. In his Introduction, Dion writes the following:

“The chapters are about a lot of things. They’re about being a singer, songwriter, and performer. They’re about growing up a sports fan in New York City in a certain time. They’re about being a husband, a dad, and a grandfather. They’re about being Italian-American and loving my heritage. They’re about having addictions and dealing with them. They’re about having very few virtues and lot of attitude – and not dealing so well with the latter!

To Live Is Christ

“They’re about a lot of things, but they’re really about one thing. They’re about Jesus Christ. In this respect at least, I’m like St. Paul: ‘For to me, to live is Christ’ (Philippians 1:21), so Jesus kind of figures in everything, from the music to the Yankees to the pasta.” (p. x11)

For me, the book was not only a kind of introduction to rock music but to the world of rock stars. It reminded a bit of Martin Scorsese’s HBO documentary film about Beatle George Harrison: “George Harrison: Living in a Material World.” Though there are probably many differences between Harrison and Dion, both eventually were interested in the spiritual dimension of human living.

There is one section in Dion’s book that especially interested me as a philosopher. Dion was attending a dinner at which many Italian-American celebrities were present. One artist gave a talk in which he warned the members of the audience to be wary of anyone who tells them that he or she has the truth.

The speaker encouraged his listeners to flee such a person because there is no objective truth and anyone who says that there is truth is a fanatic.

Dion correctly perceived that the speaker was contradicting himself. If there is no truth, then what the speaker was saying was not true. If the speaker thought that what he was saying was true, then he was contradicting himself in saying there is no truth. Of course for a person to think that he or she knows that there is no truth is the worst example of dogmatism and of relativism.

I was delighted that Dion picked up on the contradiction. Among students in my philosophy classes at St. John’s University, I run into relativism. My experience leads me to suspect that most college freshmen in our country are relativists. The good news is that if I can spend some time with students and help them to reflect on the nature of truth, their relativistic views seem to dissolve.

What is most inspiring in Dion’s story is his conversion, which eventually leads him back to his Catholic faith. With impressive honesty, Dion reveals his personal problems and also the problems of many who were close to him either through family or in the world of rock music. All conversions are mysterious and perhaps not even the person who experiences one can clearly articulate what happened.

I recall one occasion, after I had given a lecture, a woman, who was not Catholic, came up to me and asked why I had become a priest. I tried to explain that there was no way that I could clearly explain my vocation because it involved at least three mysteries: the mystery of God, the mystery of me and the mystery of my relationship with God. For me to explain clearly why I became a priest, I would have to understand completely those mysteries.

The woman soon lost interest in my attempted response to her question, but I don’t think readers will lose interest in Dion’s story.

Next week: A closer look at Christ’s Resurrection.[hr] Father Robert Lauder, a priest of the Diocese of Brooklyn and philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica, writes a weekly column for the Catholic Press.