by James Breig

During World War II, the millions of servicemen and women deployed around the globe wanted to remain connected to home not only through letters from family members but also via newspapers. For example, Sgt. James Bailey, a Virginian writing from New Guinea in 1944, thanked his mother for sending him copies of the local newspaper and joked, “I can keep up with the local scoundrels.”

It was the same for Pvt. (later Cpl.) John La Barbera from Our Lady of Sorrows parish in Corona. Two recent articles in The Tablet have recounted his letters to a friend and the reactions of his relatives to the discovery of his mail from the South Pacific. He, too, wanted news – both from the friend, Bob Ebersold, and from the parish newsletter to which Bob contributed.

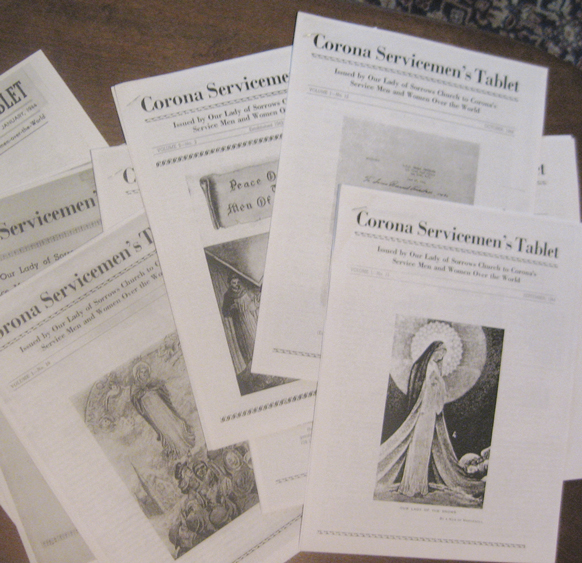

Thanks to a reader of The Tablet, several copies of that monthly newsletter, “Corona Servicemen’s Tablet,” have surfaced. It was, as noted on the front page, “issued by Our Lady of Sorrows Church to Corona’s Servicemen and Women over the World.” The publication debuted in November, 1943.

The surviving copies were saved by the parents of Robert and Louis Anastasi, who were in the Navy. Their father was a pressman who helped with the publication of the newsletter. In an interview, Louis Jr., who now lives in Flushing, said the newsletter reached him during his tours of duty in both the Atlantic and Pacific.

“I loved that paper,” he enthused. “It gave me the local news of the parish and Corona. I never realized how much I missed Corona and 101st St. The parish had a lot of friendly people and a great group of priests. I remember reading the whole paper, especially about my buddies in the Marines, Army and Navy.”

In a letter to Ebersold, written on Dec. 13, 1943, from Guadalcanal, La Barbera said, “I received the first issue of The Tablet, and all I can say is that it is one swell paper and I enjoyed every word of it (as) also did the boys down here who read it. So far as I know, our parish is the only one that is doing anything like that… Keep up the good work.”

La Barbera’s name would surface again and again in the newsletter. The June, 1944 issue noted that he “has gone from the Solomons to the Admiralty Islands. The Japs and cocoanuts are his chief worries now.” In September, the paper announced that he had “received a commendation for outstanding performance and loyalty under trying conditions.”

In February, 1945, another letter from him was published. In it, he recounts meeting a fellow parishioner, Anthony Bagnate, in the South Pacific, “the first person in twenty-six months overseas that yours truly knew as a civilian.”

News, Commentary and Updates

Each issue of the newsletter consisted of several 8.5 x 11-inch pages of poetry, news, commentary and updates about the estimated 5,000 men from the parish who were in the armed forces. For instance, the January, 1944 installment told how “Jim O’Rourke, Ensign in Merchant Marine, (was) arm and arming with Pat McConnell” at the parish’s minstrel show, while “S/Sgt. Eddie Germano, and Sgt. Ed. Jeantet, both stationed in Panama, sometime meet in Panama City for a little tete-a-tete.”

The same gossip-style article reported on men in England, a parishioner in the Pacific fleet, “seeing duty around the islands” and “Pete DiZinno…in the Aleutians.” Joked the author, “We won’t have any ‘Aleutians’ about the Japs with you up there, Pete.” Remarking on a medical corpsman in the Solomon Islands, the writer warned him, “If you come across any (natives), don’t ask them, ‘What’s cookin’, they may take you up on it.”

The column grew more serious when it listed members of the parish who had been wounded in action. For instance, special notice was taken of Cpl. James E. McGee, who “was wounded during the Battle of Kasserine Pass” in North Africa. McGee, who lost his left foot in the conflict, received a Purple Heart, Silver Star and Legion of Merit Award.

Other regular features in the newsletter included “Unconditional Surrender,” which reported on weddings in the parish, “Infan-Tree” about births and “Silly Salvos,” a column of jokes, such as this one: “An American airman in Iceland … wrote to his parents: ‘It is so cold here that the inhabitants have to live somewhere else.’” The compiler of the column admitted his contributions were “a salvo of corn.”

The cover of “Corona Servicemen’s Tablet” changed from issue to issue. In April, 1944, it showed an image of Our Lady of Sorrows. In June of that year, it was a drawing of Christ that a parishioner, Pvt. Fearonce LaLand, had sent to his mother. The January, 1945 cover was a photograph of then-Archbishop Francis J. Spellman giving communion to troops in France, including Tommy Fitzgerald, a graduate of Our Lady of Sorrows School.

The front of the final edition of the newsletter in August, 1945 was a drawing of the Blessed Mother, holding Jesus’s body at the foot of the cross. That Pieta was surrounded by scenes of suffering during the war: a Chinese mother holding her baby, a shattered battlefield labeled “China” and two soldiers helping a wounded buddy. Another soldier knelt before the scene.

Inside, Father William F. Murray, moderator of the newsletter, noted that “the war being ended, … our young folk in service of their country are fast returning to civilian life.” With wartime censorship ending and people overseas more able to get the news, he continued, “the assistance of our little monthly would be superfluous … May God grant no more wars – at least in our lifetime.”

The last issue also listed men who had been killed during the war. Among them was Fearonce LaLand, the 26-year-old who had drawn the picture of Jesus for his mom. He died in Italy the day after he mailed the image to her.[hr]

James Breig, a veteran Catholic journalist, is the author of “Searching for Sgt. Bailey: Saluting an Ordinary Soldier of World War II.” The book is based on letters he found that were sent by a soldier in New Guinea to his mother. It is available at www.amazon.com.