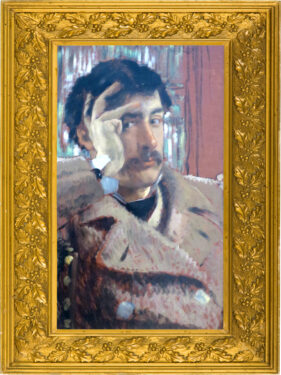

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — While the name James Tissot may not be as famous as fellow French artist Edgar Degas or the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, he was revered by them.

Tissot (1836-1902) achieved commercial success painting images of French and English society. As his fame grew, he strayed from the Catholic faith of his youth but eventually found his way back after a spiritual encounter at a Paris church.

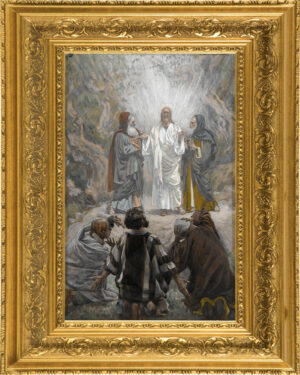

This pivot led to some 350 watercolors depicting the life of Jesus, originally intended for an illustrated version of the Bible. The vivid paintings were informed by Tissot’s dogged historical research during multiple trips to the Holy Land.

For over a century, their home has been the Brooklyn Museum, which acquired this collection of faith paintings, “The Life of Christ,” in 1900. Last month, the museum began displaying two of the watercolors in a special exhibition to celebrate the museum’s 200th anniversary, according to Danielle Villaluna, the museum’s senior manager of public relations and communications.

Tissot’s contemporaries celebrated his influence. Degas and the American painter James Whistler formed his circle of acquaintances. But, in the Netherlands, Vincent van Gogh wrote: “A discerning critic once rightly said of James Tissot, ‘He isa troubled soul.’ However this may be, there is something of the human soul in his work and that is why he is great, immense, infinite.”

Fundamental to Catholicism

Dr. Laura Auricchio, an art history professor, called Tissot’s religious-themed watercolors “a massive undertaking” that depict Jesus’s time on earth. Auricchio is the new vice president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in Manhattan. Until Oct. 4, she was the dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center.

Her field is 18th century European art, and along the way she learned about Tissot. Auricchio explained that “The Life of Christ” gives viewers a unique perspective of what Jesus saw with his own eyes. A great example of that is the watercolor titled, “The View from the Cross.”

Here, people get an elevated view of Mary, other distraught women, and the Apostle St. John at the foot of the cross. Surrounding them are soldiers and casual bystanders.

“It’s pretty daring to have an image that puts the viewer in the position of Christ,” Auricchio said. “I don’t know that I’ve ever seen it anywhere before. “But the idea of being there and imagining yourself witnessing the human suffering of Christ is something that’s really fundamental to Catholicism.”

Prayed for Hours

Tissot was born in 1836 in Nantes, France, as Jacques Tissot, but by age 17, he preferred to be called James. Around that time, he moved to Paris, where he studied painting, according to the 1984 biography, “James Tissot,” by Michael Wentworth.

tament prophets Elijah and Moses, witnessed by his disciples Peter, James, and John.

Tissot’s technique and fame in France grew in the 1860s, especially for his depictions of feminine beauty and fashion. His success led to wealth, which he used to acquire property.

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 led Tissot to serve as a sharpshooter in the “Artists Brigade” during the

Siege of Paris. Political upheaval related to the war spurred his move to England.

In London, he fell in love with an Irish divorcee and mother of two — Kathleen Newton. Tissot’s Catholic faith did not accept her divorce. Fearing an annulment would delegitimize her children, Tissot and Newton lived openly as husband and wife from 1877 to 1881, but outside of marriage.

As a muse and model, Newton was the subject of many Tissot paintings, even while she suffered from tuberculosis. When Newton died in 1881, Tissot prayed for hours at her coffin, which was draped in purple cloth. He returned to France and, over time, grew a deeper devotion to the Catholic faith.

A Strange and Thrilling Picture

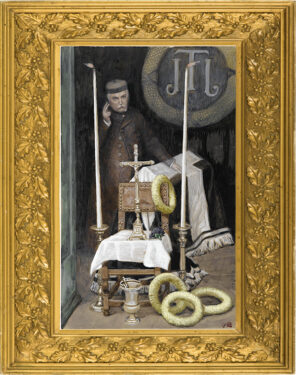

In 1885, a few years after Tissot returned to Paris, he visited the Church of St. Sulpice in search of inspiration for a painting of a fashionable woman singing in a choir. Tissot stayed for Mass, and during the liturgy of the Eucharist, he experienced a spiritual vision.

tament prophets Elijah and Moses, witnessed by his disciples Peter, James, and John.

Wentworth’s book contains Tissot’s first-person description of what happened. It states that as the host was elevated, Tissot, with head bowed and eyes closed, suddenly saw “a strange and thrilling picture” of a destitute man and his wife stopping for rest in the ruins of a modern castle.

Tissot said, a “strange figure” glided to them with feet and hands “pierced and bleeding” and head wrapped in thorns. “This figure,” Tissot recalled, “needing no name, seated itself by the man, and leaned its head upon his shoulder, seeming to say, more by the outstretched hands than in words: ‘See, I have been more miserable than you; I am the solution of all your problems; without me, civilization is a ruin.’ ”

Tissot said he then became sick with fever, “and when I was well again, I painted my vision.”

Archaeological Exactitude

He kept painting with zeal, producing some 350 watercolors of Jesus’ life. According to the Brooklyn Museum, he painted many figures in costumes that “he believed to be historically authentic, carrying out his series with considerable archaeological exactitude.”

The watercolors were received with tremendous excitement when they first appeared in 1894 in Paris. A highly publicized exhibition toured London and the U.S., including stops in Manhattan, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and, of course, Brooklyn.

In 1900, Tissot’s American friend, fellow painter John Singer Sargent, was a consultant to the Brooklyn Museum, advising it on acquisitions. He suggested the museum buy “The Life of Christ” series. The purchase was achieved with $60,000 from a fundraising campaign championed by the Brooklyn Eagle.

“The Tissot paintings are among some of the Brooklyn Museum’s very first European art acquisitions and thus play a large role in the history and formation of our collection,” Villaluna told The Tablet.

Tissot died 1902 in Doubs, France. He was 65.

Limited and Unlimited Viewings

The Brooklyn Museum’s last major showing of his work was the 2009-2010 exhibition, “James Tissot: ‘The Life of Christ,’” featuring 124 of the 350 watercolors. “They are not always on exhibit as they are watercolors, not paintings on canvas,” Villaluna explained, noting that they can fade or get damaged if they receive too much light exposure. “In order to preserve them, they can only ever be on view for limited periods of time.”

Auricchio said viewing Tissot’s works in person or online is a “fantastic” opportunity to nourish one’s faith via art. “You know the saying, ‘A picture is worth a thousand words,’” Auricchio said. “Images can help us, inspire us, and bring us to understand better a kind of empathy for the lived experience of the Bible, and of Christ. “That’s really unique.