Dems say yea, Reps nay, in newly-drawn voting maps

PARK SLOPE — Voters who go to the polls next Election Day may find unfamiliar names in major places on the ballot — even if they’re lived in the same neighborhood for years and have been represented by the same elected officials.

The reason for the unfamiliarity is simple. Boundary lines for congressional, state senate and state assembly districts have been redrawn — in some cases dramatically — with a vote by the State Legislature on Feb. 2. The new maps go into effect this year.

District maps are redrawn by the Legislature every 10 years, to follow the results of the U.S. Census count, but this year’s cartography is generating controversy, because of changes to congressional seat boundaries that appear designed to maximize Democrats’ chances of winning certain elections, or solidifying their control in certain districts.

Currently, Democrats hold majorities in both houses of the state legislature, and they’re the folks who drew the new maps.

“Republicans in New York are losing the ability to run in competitive districts because these districts have been drawn to favor the party in power, which at present is the Democrats,” said Brian Browne, a political science professor at St. John’s University.

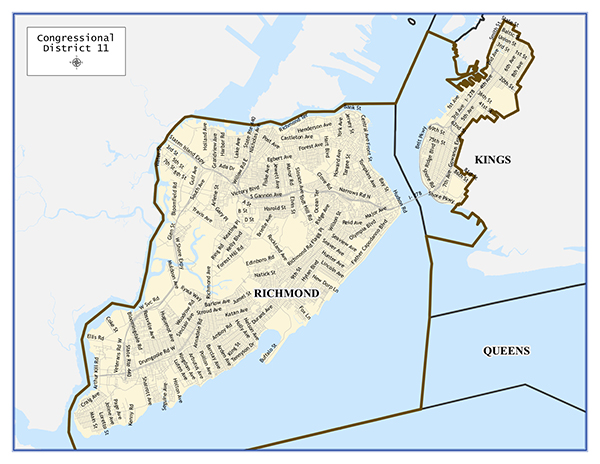

Take New York’s Congressional District 11, for example. Represented by Republican Nicole Malliotakis, NY11 currently covers Staten Island and connects to Brooklyn via the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, taking in such neighborhoods as Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights and Gravesend, where the electorate has a history of being favorable to the GOP.

But when Malliotakis runs for re-election in November, she will have a whole new set of Brooklyn voters to convince. The mapmakers have removed Dyker Heights and Gravesend from NY11 and, in their place, drawn in such traditionally Democratic strongholds as Sunset Park, Windsor Terrace and Park Slope.

However, Malliotakis’s campaign is crying foul.“This is a blatant attempt by the Democrat leadership in Albany to steal this seat,” spokesman Rob Ryan said.

“They know Congresswoman Malliotakis is popular and they can’t beat her on the merits or public policy, so they are changing the boundaries to tilt the scale,” Ryan added.

What happened in NY11, as well as the shape-shifting of the boundaries of other districts around the state, led a group of voters to file a lawsuit in state court on Feb. 3, charging that the redrawn maps are a brazen attempt at gerrymandering, which, by definition, is the “manipulation of the boundaries of an electoral constituency so as to favor one party or class.” The maps should be rejected, the lawsuit states, because they are “obviously unconstitutional.”

The moves made with another congressional seat, New York District 10, currently represented by Democrat Jerrold Nadler, is also raising eyebrows. Under the new map, NY10 is an S-shaped district stretching from the Upper West Side all the way to Bensonhurst — snaking its way across a bridge and through several neighborhoods and which, in some spots, is only a few blocks wide.

NY10 has always stretched from the Upper West Side to southern Brooklyn, but the district is attracting more scrutiny after the latest redistricting process.

There are estimates that Democrats could pick up as many as four congressional seats in New York State in mid-term elections this November.

New York’s current House delegation consists of 27 members — 19 Democrats and eight Republicans. New York stands to lose a congressional seat as a result of the latest Census count.

Democrats, meanwhile, are defending the new district lines.

“We’ve come up with fair maps that the state can be proud of,” Senate Majority Leader Michael Gianaris, a Democrat from Queens, told reporters.

Ironically, the redistricting process wasn’t supposed to be controversial.

In 2014, voters approved a referendum calling for the district lines to be drawn by an independent, bi-partisan commission. A panel — the New York State Independent Redistricting Commission — was formed, but its 10 members — five Democrats and five Republicans — couldn’t agree on final solutions. As a result, the Legislature stepped in.

“What we’re seeing now is a byproduct of a failed process,” Browne said.

Gerrymandering isn’t unique to New York, Browne said, noting that “in some other states, it’s the Republican majority controlling the process. There’s equal blame to go around.”