PROSPECT HEIGHTS — On Oct. 29, 1853, Harriet Thompson took pen to paper, wrote a letter to the pope, and started a fight for equality for blacks in the Catholic Church.

Thompson, a black woman living in Lower Manhattan, was unhappy with the treatment she and her fellow African Americans were receiving not only from society but from the Church as well. So she took her concerns to the man at the top — writing a letter to Pope Pius IX.

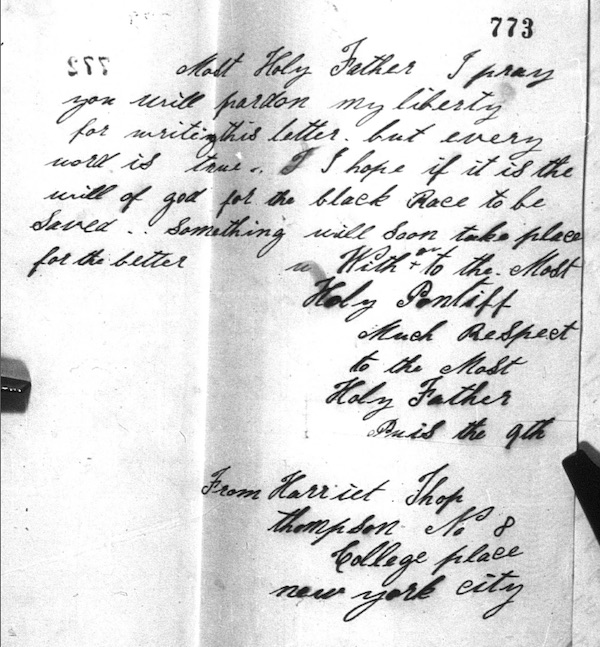

In her eight-page missive, Thompson implored the pontiff to “provide for the salvation of the black race in the United States who is going astray from neglect on the part of those who have to care for souls.”

According to many historians, Thompson’s letter marked the beginning of the Black Catholic Movement in the U.S., which stretched well into the 20th century.

In her letter, Thompson didn’t hold back. She charged that since many priests and bishops were immigrants who hailed from countries where there were few black people, they were simply unaware of how to minister to her people.

“Hence, it is a great mistake to say that the church watches with equal care over every race and color, for how can it be said they teach all nations when they will not let the black race mix with the white,” she wrote.

When Thompson wrote her letter, Catholic churches and schools were still segregated.

John Slattery, director of the Carl G. Grefenstette Center for Ethics in Science, Technology, and Law at Duquesne University, said what’s striking about the letter is the time in which Thompson lived.

“This was before the Civil War. There was slavery in much of the country. For a black woman at that time to feel she could speak freely and frankly is quite remarkable. Imagine having the gall to write to the pope,” he said.

Slattery, who studies how science, law, and race intersect, found the letter fascinating when he first learned of it.

“Historically, the letter is significant, not because Harriet Thompson plays a big role in black policy in the United States. There’s no record of her holding leadership positions. So the significance of the letter isn’t that she brought a bunch of black Catholics together. But it’s a representation of the voice of a community and a group of people that are sort of being oppressed from multiple sides,” he explained.

Slattery was impressed by Thompson’s frankness. “I thought that her voice was a really interesting one and represents what some people have called ‘The Turn to Rome’ for American black Catholics; that they weren’t finding any help in the continental United States,” so they asked the Vatican to intervene, he said.

Pope Pius IX never answered the letter, although it is considered historic enough to be stored in the Vatican archives, along with a note written in Italian, indicating that the letter had been passed on to the Holy Father. “Referred to the Blessed Father,” the note read.

Thompson’s letter remains at the Vatican, where it is stored in the archives of the Congregation of the Propagation of the Faith.

Decades ago, scholars from the University of Notre Dame traveled to Rome, examined the letter, and took photos of it, which they stored on microfilm.

Despite the fact that her letter has such historical value that it is stored in the Vatican, not much is known about Harriet Thompson. “She kind of disappears after that letter,” said Slattery, who has searched census tracts for any record of her and came up empty. And no photographs of her have been known to exist.

In some ways, that’s not surprising, Slattery said. “Within a few years of her writing that letter, the country would be thrown into chaos due to the Civil War,” he explained, adding that records might have been lost.