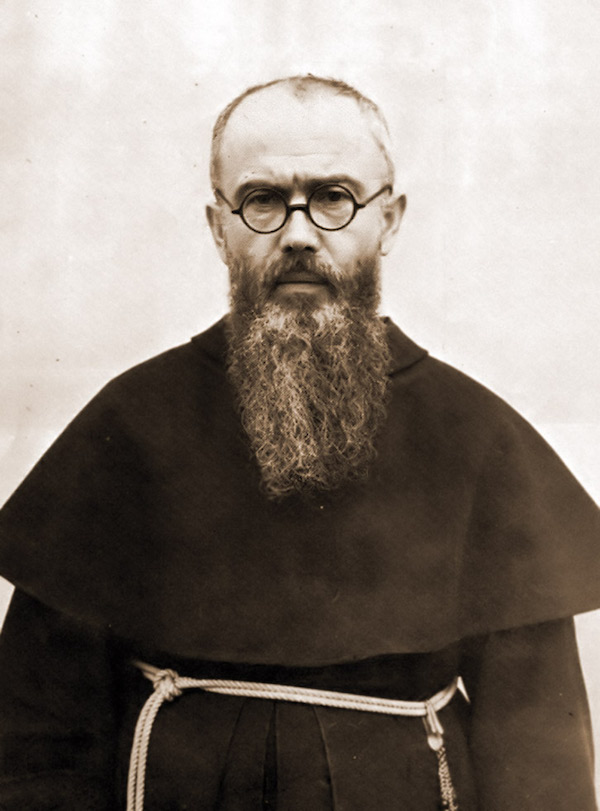

ROCKVILLE CENTRE — St. Maximilian Kolbe was a Franciscan friar in Poland who was arrested by the Germans in 1941. His crime? Opening the doors of his friary to provide a hiding place for Jewish people seeking to escape Nazi persecution.

He was sent to Auschwitz, where he was subjected to frequent beatings and starvation when he refused to stop professing his Catholic faith. In a final act of heroism, he offered to take the place of a Catholic Polish army soldier named Franciszek Gajowniczek who was set to be executed. The Nazis took Father Kolbe up on his offer, and killed him by lethal injection on Aug. 14, 1941.

Father Kolbe was canonized by St. Pope John Paul II in 1982. In a twist of fate, Gajowniczek, the man whose life he saved, survived the Holocaust survived the war and became a lay missionary, dedicating his life to spreading the story of Kolbe’s sacrifice and was present at the canonization.

“One of the last things St. Maximillian Kolbe said was ‘Hate is never a creative force. Love is a creative force,’ ” explained Msgr. Anthony Figueiredo, a Vatican consultant who came to the Diocese of Rockville Centre to celebrate a Mass at the Cathedral of St. Agnes in Father Kolbe’s memory on Aug. 14, the 82nd anniversary of his death.

Father Kolbe’s story is just one of many inspiring tales of heroism displayed by Catholics during the dark years of the Holocaust.

Read More: In WW II Poland, Caring Catholics Protected Jewish People

There is a small museum in Assisi, Italy, dedicated to preserving the memory of priests and nuns who helped save approximately 300 Jewish people — many of them children — by forging documents for them, sheltering them in convents and monasteries, and smuggling them out of the country.

Called the Museum of Memory Assisi, 1943-1944, it was established in 2010 and is housed in the Vescovado (Italian for bishop’s palace) in Assisi. The museum tells little-known stories of the Holocaust.

Msgr. Figueiredo, who serves as director of international relations for the Diocese of Assisi, was also in Rockville Centre to talk about a traveling exhibition from the museum slated to tour Catholic high schools on Long Island this fall. The upcoming tour is sponsored by DeSales Media Group, the ministry that produces The Tablet.

It will mark the second time the traveling museum has come to New York. In 2022, it was on display at St. John’s University in an exhibition sponsored by the Pave the Way Foundation, an organization promoting dialogue between religions.

“The Museum of Memory is valuable because it does a good job of setting the record straight,” said Gary Krupp, founder and president of the foundation.

While many historians allege that Pope Pius XII remained coldly silent as Jewish people were persecuted and slaughtered, a revisionist view has emerged in recent years calling attention to the many acts of heroism displayed by everyday Catholics who risked their lives to save Jewish people.

The Museum of Memory Assisi is a good way to honor them, Msgr. Figueiredo said. “One wonderful artifact in the museum is the printing machine that was used to print out the forged documents for the Jewish people,” he explained.

“It’s fascinating because without that happening, our Jewish brothers and sisters would not have been saved. The bishop allowed these documents that changed the names of the Jewish people to Italian names,” he added.

Bishop Giuseppe Nicolini, the bishop of Assisi at the time, hid the Jewish people’s original identity documents in the basement walls of his residence with an eye toward eventually returning them to their original owners, Msgr. Figueiredo explained. “He would come downstairs with a hammer and chisel and he would knock out bricks from the wall in his basement to put the documents in,” he added.

Bishop Nicolini wasn’t the only Catholic leader to instruct priests and religious to shelter Jewish people, Krupp said. “It was happening in other places. People worked through a network that was actually mastered by the Holy See. Pope Pius XII comes under a lot of criticism for staying silent. He was working in secret to save my Jewish brothers and sisters,” added Krupp, who is Jewish.

Msgr. Figueiredo said he is particularly excited about a new artifact the museum recently acquired: a bicycle that belonged to Gino Bartali, a famous Italian cyclist who won the Tour de France in 1938 and helped save Jewish by hiding documents in his bike’s crossbar.

With anti-Semitism on the rise in the U.S., now is a perfect time to bring the traveling exhibition to high schools, Msgr. Figueiredo said. “We overcome evil with good and that’s why we need to bring our museum to young people, because young people really have it in them to fight for change,” he explained.

According to the Anti-Defamation League, overall anti-Semitic incidents rose 36% between 2021 and 2022. Acts of vandalism against Jewish institutions increased 51%, and incidents of harassment rose 29%.

“This is much more than a museum. It’s a message,” Msgr. Figueiredo said. “What is that message? Never again, never again to anti-Semitism.”

Simple question-

Where and when can we see the exhibit??