By Mark Zimmermann

WASHINGTON (CNS) – Washington’s newest monument – the National Museum of African American History and Culture – opened in September 2016 to wide acclaim.

Its dedication was attended by dignitaries including then-President Barack Obama, the nation’s first African-American president, and former President George W. Bush, who had signed the 2003 act of Congress creating the museum.

Located near the Washington Monument, the new museum designed by architect David Adjaye has a three-tiered shape inspired by a traditional Nigerian column and crown, with 3,600 bronze-colored cast aluminum exterior panels inspired by ornate ironwork fashioned by enslaved craftsmen in 19th-century New Orleans, La.

In its first four months, the museum has become one of the most popular attractions in Washington, as it welcomed nearly 750,000 visitors, and its allotment of hourly timed passes reserved online months in advance, with a limited number of passes available online and for walk-up visitors each day.

A History Often Hidden

The museum with its more than 36,000 artifacts tells a story of a history that has been often hidden, but resonates today with Americans of all backgrounds.

One week after the museum opened, two friends from St. Teresa of Avila parish in Washington, Donna Grimes and Charlene Howard, toured its exhibits together. Both have deep African-American Catholic roots.

Grimes is the assistant director for African-American affairs in the Secretariat of Cultural Diversity in the Church at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). Howard is a religion teacher at Archbishop Carroll High School in Washington, where she teaches a social justice class.

Both women said they were profoundly moved by the experience.

“I’m just glad we have it now. All the things our parents told us about, or we had to read about” or go find at certain places, “the truth is now there for everyone,” Howard told the Catholic Standard, newspaper of the Washington Archdiocese. “I felt like, it’s about time!”

Grimes was impressed by the crowds of people who, like her, were taking it all in.

“I was watching parents with children, grandparents, young adults and young couples. I was watching their impressions too,” she said.

One of the first exhibits that caught her eye was about Queen Nzinga, a 17th-century leader of what is now Angola, who converted to Catholicism and was known for her diplomatic skill and fought wars and negotiated peace with the Portuguese who were engaged in a brutal slave trade in that region.

“The first thing I see from the motherland is an African woman who is Catholic,” said Grimes. “She was a significant person and advocate for her people.”

The USCCB official said she was moved by the displays on the geography of slavery – the nations involved in the slave trade, and where the slaves lived.

Metal shackles used to restrain children and adults are displayed, and a display notes that the trans-Atlantic slave trade involved tens of thousands of ships and “the largest forced migration in human history” – with an estimated 12.5 million slaves brought from Africa to the Americas from the 1500s to the 1800s.

Another display notes that the average lifespan of enslaved Africans working at tropical sugar and rice plantations was seven years.

The museum’s five levels of exhibits are replete with ironies. Thomas Jefferson – who penned these words of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” – is depicted in a statue, surrounded by bricks containing the names of the 609 slaves, including some of his own children, whom he owned in his lifetime.

“American independence brought liberty for some, but not all,” the exhibit notes.

That gallery also points out that enslaved African-Americans mined sandstone from local quarries and helped build the U.S. Capitol, the White House and the Smithsonian Castle.

Ashley’s Sack

“There were things I knew, but things I didn’t know,” Grimes said. “I think the part that got to me the most was the separation of families.”

One of the most searing items on display is “Ashley’s sack,” a cotton sack embroidered with the story of a 9-year-old girl who in the mid-1800s was sold and separated from her mother, who gave her the sack to keep and put a lock of her hair inside along with a few handfuls of pecans, telling her “it is filled with my love always.” They never saw each other again. In 1921, Ashley’s granddaughter sewed that story onto the sack, which had remained a precious family keepsake.

As a teacher, Howard was inspired by the “multiplicity of ways to get information” at the museum, from photos to paintings to artifacts to videos and audio recordings. They trace the story of the nation’s African-Americans from times of slavery and reconstruction, to segregation and the rise of the civil rights movement, to current struggles for racial justice and equality.

People can walk by an actual slave cabin from South Carolina and a segregated Southern Railway rail car, and look up and see a plane that was once flown by the Tuskegee Airmen. They can hear the voice of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Obama. Other displays show cultural artifacts, like Louis Armstrong’s trumpet and Muhammad Ali’s boxing robe, and people can see and hear the impact that black Americans had in music, sports, television and movies.

Visitors also can sit at a replica of the Greensboro, N.C., Woolworth’s lunch counter, and touch screens to link with various aspects of the struggle for civil rights.

The artifacts include the casket of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy whose lynching in Mississippi in 1955 helped galvanize the civil rights movement. His murder inspired the activism of Rosa Parks, who was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala.

Also on display is a drinking fountain with the sign “White/Colored,” showing the everyday indignities that black Americans endured during segregation.

“By seeing history, it will answer questions people have about the roots of problems we’re confronting today,” Grimes said, adding, “People need to know that history, what the struggle has been.”

Grimes noted that in the mid-1950s, her mother wrote a report on the Underground Railroad, but her teacher, a Catholic sister, “would not accept it, and said it was not true.”

Harriet Tubman, an escaped Maryland slave who later helped lead people to freedom through the Underground Railroad, was announced last year as the person who will replace Andrew Jackson, the nation’s seventh president, on the $20 bill. Tubman’s artifacts at the new museum include her hymnal and a lace shawl given to her by Queen Victoria.

The exhibit described Tubman as “a fiercely religious woman” and added that “the wear and tear on this hymnal suggests that she must have loved it and used it frequently.”

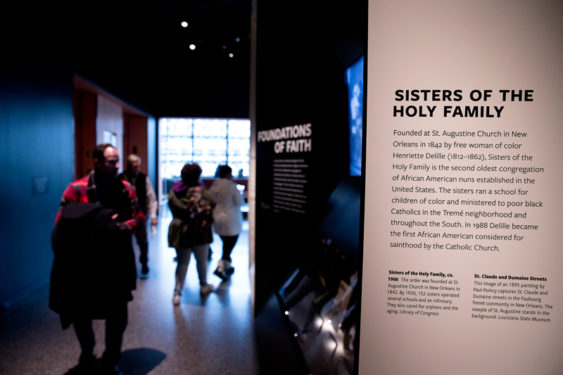

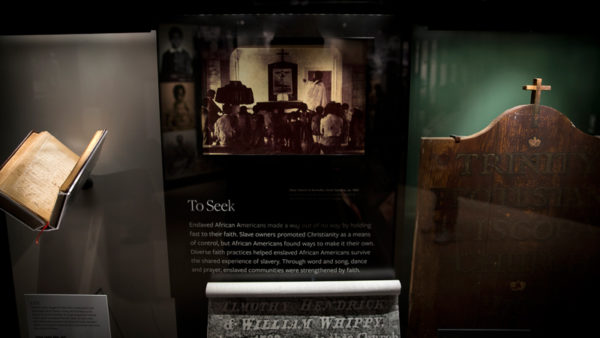

The National Museum of African American History and Culture highlights the important role that churches and people of faith played in the struggle for freedom and civil rights, and the artifacts on display include an oak church pew, a podium and organ.

“Many schools, local social agencies and other organizations that emerged after the Civil War had their beginning within the walls of African-American churches,” the exhibit notes.

A photo of John Lewis – the civil rights leader who now serves in Congress – shows him marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, and a Catholic woman religious in full habit can be seen walking beside him in the crowd.

Interwoven with Faith

Noting the museum’s recognition of faith in African-American history, Howard said, “That underscores the nature of our cultural heritage. Faith is interwoven with who we are. It’s in our DNA. That comes from Africa, (where) people don’t separate faith from life.”

That devotion to faith, she said, links today’s African-Americans to their ancestors, and to their family members who are not yet born.

For visitors to the National Museum of African American History and Culture like Grimes and Howard, the wait has been worth it – the years it took to plan and build the museum, and the wait involved in getting a timed entry pass and standing in the line that snakes around the building every day.

“I felt our story was being told by us,” said Howard. “It was driven by an African-American world view, by people of color who come from that experience. That is a first. Now on the national stage, we are telling our story from our perspective, and that’s huge.”

She added, “It’s truth. It’s our story.”