by Francis X. Rocca

VATICAN CITY (CNS) – When Pope Francis travels to South Korea, Aug. 14-18, he is ready to find a Catholic Church that exemplifies much of what he hopes for the Church around the world, including a highly active laity, extensive efforts to help the needy and strong relations with non-Christian communities. So says a retired American missionary who spent nearly half a century building up Catholicism in the country.

Bishop William J. McNaughton, 87, arrived in Korea as a Maryknoll missionary in 1954 and served as the first bishop of Inchon from 1962 until his retirement 2002. The bishop is watching Pope Francis’ visit on television from Massachusetts, where he lives with one of his sisters.

“The blood of martyrs is why the church is so strong in Korea,” the bishop said, noting the more than 10,000 Korean Catholics killed for their faith between 1785 and 1886, 124 of whom Pope Francis was scheduled to beatify Aug. 16.

“To this day, they talk about it, they urge people to have the spirit of the martyrs,” the bishop said.

One legacy of that persecution is an extraordinarily prominent role for lay Catholics. The church was founded in the late 18th century by laypeople who embraced Catholicism after studying it in books imported from China, and for more than half of its first century, it had to survive without the ministry of clergy.

That tradition manifests itself today in the popularity of ecclesial movements such as the Legion of Mary, Cursillo, Marriage Encounter and the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, Bishop McNaughton says. What’s more, he says, “everybody sings” in church.

Lay Evangelizers

In Korea, the “evangelizers are not so much the priests and the sisters as the very persons themselves, the Catholic laity,” he said. “Once they get the faith, they propagate it among themselves. They know how to spread the faith.”

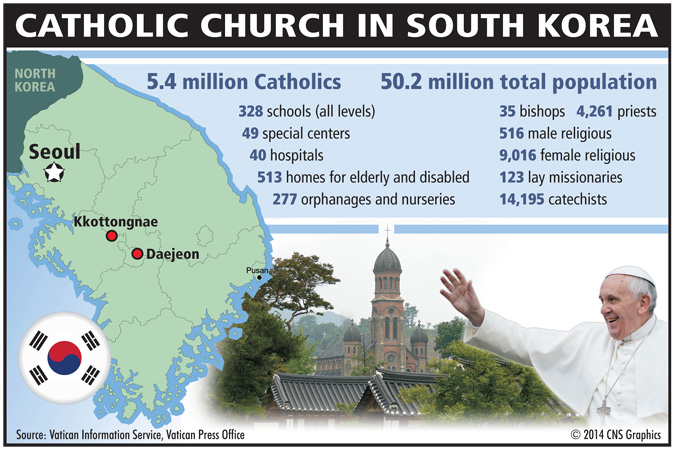

Yet the bishop, whose achievements included opening a diocesan seminary, notes that Korea has a strong tradition of cultivating native clergy, starting with a clandestine seminary founded in the mountains in 1855. At the end of 2013, according to statistics supplied by the local church, South Korea had 4,261 priests and 1,489 major seminarians out of a total of 5.4 million Catholics (almost 11 percent of the country’s population).

Notwithstanding Korean rulers’ long-standing hostility to Christianity, which was banned until 1886, Bishop McNaughton says the local culture is naturally receptive to it.

One reason is the deep-rooted religiosity, whose traditional forms include Buddhism, Laoism and Confucianism.

“There are very few atheists,” said the bishop, noting that he enjoyed cordial relationships with Buddhist monks as well as Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries during his years in Korea.

The typical strength of extended families in Korea is also conducive to Catholicism, since converts tend to share their faith with relatives, he says. Weddings and funerals are especially propitious occasions, where non-Catholic guests can be “edified by the beauty” of the liturgy.