I am not certain when I began to read the Jesuit weekly, America. Probably I ordered my fist subscription when I was a college seminarian. Frequently, from the pulpit, I urge members of the congregation to read some Catholic periodical regularly. In our very secular society, the 10-minute homily is just not enough to form and shape our consciences. In my own life, I have found the regular reading of America a great help. Every so often there is an essay that seems to be written with me in mind. In the March 18, 2020 issue such an essay was “The Startling Prayer Life of Soren Kierkegaard” by Karen Wright Marsh.

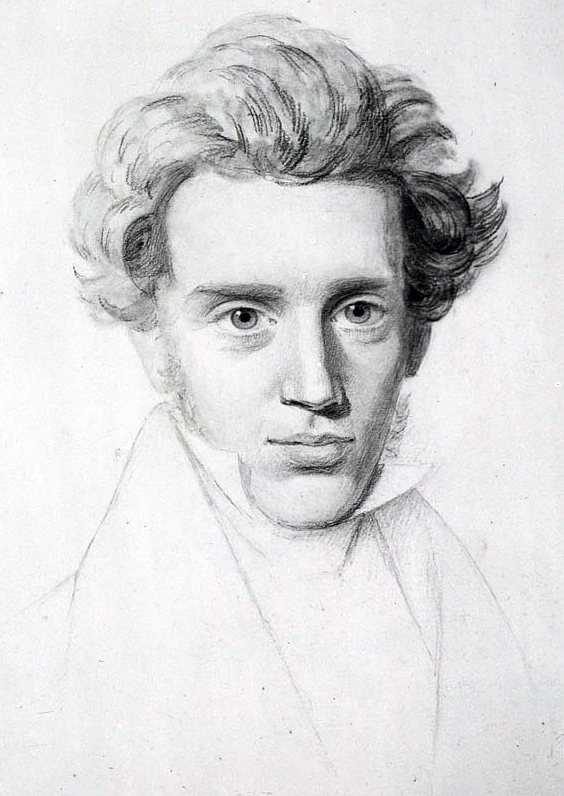

I first read Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), generally recognized as the father of the philosophy of existentialism, when I was in graduate school. Almost immediately I was hooked.

In philosophy classes I teach at St. John’s University, I have fallen into the habit of telling the students who my favorite philosophers are and why they are my favorites. I do this not to encourage students to agree with me but rather so that they have some idea of my preferences in philosophy. After they understand from where I am coming, they can decide whether they agree or disagree with the philosophical thinkers I present to them. When I start to lecture on Soren Kierkegaard, just about the first words I speak are: “I like Kierkegaard’s philosophy very much. I love his emphasis on freedom.”

Though in the minds of many who have not had the opportunity to study philosophy, existentialism is associated with atheism, Kierkegaard, the first existentialist, was deeply religious. Karen Wright Marsh’s essay was a special blessing for me because before reading it, I knew next to nothing about how Kierkegaard prayed.

Wright starts her essay by quoting the following prayer of Kierkegaard:

“Where am I? Who am I?

How did I come to be here?

What is this thing called the world?

How did I come into the world?

Why was I not consulted?

And if I am compelled to take part in it, where is the director?

I want to see him.”

The prayer seems to me to be the perfect prayer for a Christian existentialist. Early in the course I teach on existentialism, I suggest that in the course we will try to understand, as deeply as we can, our identity and we will use the philosophy of existentialism to guide us.

Kierkegaard believed that there were three ways of living or three stages on life’s way or three spheres of existence. The first he called the aesthetic. This was a commitment to sense pleasure in this world. On this stage, freedom was license, freedom meant doing what you felt like doing. A model for this could be Don Juan. On this stage, there is no commitment to anything beyond sense pleasure, no sense of transcendence. The logical termination of this way of living is suicide.

Why? Because the person on this stage is trying for personal fulfillment where it cannot be found, namely in sense pleasure. Though suicide is a logical termination to living on the aesthetic stage, it is not a necessary step. A person can leap to the second stage which Kierkegaard called the ethical stage. On this level, a person has a strong sense of duty and a commitment to the law. This is better than the aesthetic stage but it still will not fulfill an individual.

For fulfillment, an individual should leap to the third stage, which involves a commitment to God. The third stage has four characteristics according to Kierkegaard: it is inward, it is subjective, it involves a leap and it is absurd.

By inward Kierkegaard suggests that a person reaches a depth on the third stage. To live on the third stage is not to live superficially. Freedom has found its proper direction on the third stage. By subjective Kierkegaard did not mean arbitrary but rather personal. The third stage reminds me of Buber’s description of an I-Thou relationship with God. An individual has been called by God and the individual has responded freely.

By leap, Kierkegaard meant risking everything on faith in God. The individual who has made the leap believes that he has encountered God but he cannot prove that to others. In fact he himself cannot completely understand the leap. By absurd Kierkegaard did not mean that the religious stage made no sense but rather that it was so meaningful that no one could understand it completely.

For Kierkegaard, the absurd on the third stage of living meant that the person lived in mystery. There was too much meaning for the human mind to comprehend completely the third way of living.

Kierkegaard is an excellent example of a profound thinker whose insights and ideas still have the power to motivate and inspire many years after the thinker has died.

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, every Tuesday at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.