EDITOR’S NOTE: The Diocese of Brooklyn is known as the “Diocese of Immigrants.” Its international flavor means that Mass is celebrated in dozens of languages and church pews are filled with parishioners of many nationalities. With that in mind, The Tablet is taking a look at how the different cultures represented in the diocese celebrate Christmas. This week, we focus on Nigeria, Brazil, the Philippines and Vietnam.

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — Father Cosmas Nzeabalu, parochial vicar for St. Mary Magdalene Church in Springfield Gardens, has fond memories of the Christmases he spent in his home country of Nigeria.

“Christmas is a very special season for us. Our lives center around the church and I remember the joy and excitement we felt on Christmas Day,” said Father Nzeabalu, who is the coordinator of the Nigerian Apostolate for the Diocese of Brooklyn.

Approximately 10% of Nigeria’s 218 million people are Catholic, and Father Nzeabalu explained that in the small villages that dot the country’s landscape, people tend to live in extended families with everyone from grandparents to parents to children, aunts, uncles and cousins all residing under the same roof.

Nigerian Christmas traditions include families all dressing up on Christmas Day in identical clothing created with custom-made designs on the fabric that are unique to that particular family.

Families attend midnight Mass together and enjoy fireworks displays after church. On Christmas Day, wealthy families have cows or goats slaughtered with the meat from the animals used for the main meal. Many families donate the meat to the less fortunate.

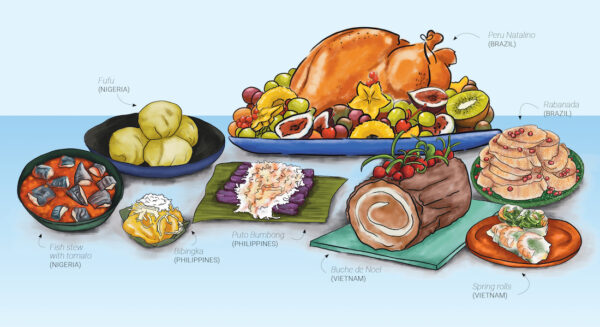

Traditional Christmas dishes include rice with FuFu, a type of sticky dough commonly found in West African cuisine. Another popular dish is white rice mixed with palm kernel — the edible seed of the oil palm fruit.

“Families also like to make stew. They will make different kinds of stews with rice,” Father Nzeabalu added.

Father Jose Carlos da Silva’s native country, Brazil, boasts the world’s largest floating Christmas tree — a 542-ton tree decorated with 3.3 million lights that floats on the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon in Rio de Janeiro.

Despite this, Father da Silva, pastor of St. Rita’s Church in Long Island City and coordinator of the Brazilian Apostolate, said decorations are secondary and that Brazilians focus their attention on spiritual matters, like the importance of the birth of Jesus Christ. “For us, that is the center of everything,” he said.

Brazil is a predominantly Catholic country, with approximately 55% of the nation’s 216 million people practicing the faith.

Families attend Christmas Eve together and then go home to enjoy a midnight dinner. Turkey is the traditional Christmas dinner “but we don’t make it like they do in America,” Father da Silva explained. In Brazilian cuisine, the turkey is garnished with fruits like peaches and pineapples.

Chicken is also a popular Christmas dish. Brazllians cook what are known as “chesters,” chickens specifically bred to contain a high percentage of breast meat.

We call him Santa Claus, but to Brazilian children, he is Papai Noel (Father Christmas) or Bom Velhinho (Good Old Man). A fun tradition calls for children to leave the Christmas stocking by a window in the hope that Santa Claus will spot it while flying by the house on his rounds. Tradition has it that if Papai Noel sees the stocking, he exchanges it with a present.

St. Rita’s Church will prepare for Christmas by holding a novena starting Dec. 1. “Each year, we pray as a community for something — all of us praying together for the same thing. This year, we will be praying for world peace because of the war in Ukraine,” Father da Silva explained. On Dec. 10, St. Rita’s will host its parish Christmas dinner.

“The government controls everything. But they do allow for the celebration of Christmas,” said Father Peter Hoa Nguyen, the parochial vicar for St. Francis of Assisi Church in Astoria, who was born and raised in Vietnam.

Vietnam is a Communist country, and the majority of the nation’s 98.5 million citizens do not follow any religion. But there are 7 million Catholics, and faith is a big part of their lives, said Father Nguyen.

There might be economic reasons behind the willingness of the Communist leaders to permit Christmas celebrations. “The government wants to be part of the world economy, with trade and everything. And they know they cannot shut the country off from the world,” Father Nguyen explained.

Vietnamese traditions include Christmas Eve festivals during which there are Scripture readings detailing the events leading up to Jesus’s birth. “It is like a holy festival,” Father Nguyen said.

Families typically attend Masses on both Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

The traditional Vietnamese Christmas dinner consists of duck, chicken or pig. Side dishes include spring rolls and egg rolls.

Because Vietnam was a French colony (called French Indochina) from 1862 to 1954, the country still has traces of French cuisine on its meal table. For example, a Buche de Noel, a chocolate cake in the shape of a log, is a popular dessert and is often given as a present.

Christmas in the Filipino tradition focuses a great deal on Mary, the Mother of Jesus, said Father Patrick Longalong, pastor of Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Queens Village and coordinator of the Filipino Apostolate.

The Philippines is the only predominantly Catholic country in Asia — 86% of its 111 million citizens are Catholic.

In the Philippines, there is a series of nine Masses, called the Simbang Gabi, taking place in the days leading up to Christmas starting on Dec. 16 and ending Dec. 24. “Technically, the Masses are a message for the Virgin Mary. We journey with her in her pregnancy toward the birth of Jesus,” Father Longalong explained.

The Masses used to take place in the early morning at 4 a.m. But that changed when the Philippines came under martial law in 1972 on the orders of Ferdinand Marcos.

“They used to wake up really early to go to Mass. But then during martial law in the Philippines, they decided to just do it in the evening because there was a curfew. With the curfew, you cannot go out too early in the morning,” Father Longalong said.

Filipinos traditionally attend midnight Mass on Christmas and then stay up all night. “Midnight is very big. You go to midnight Mass and then you come home, have what we call the Nochebuena, which is the meal after midnight. That’s when we start opening presents,” Father Longalong said.

The celebration goes on for hours. “It’s an all-nighter, as they say,” he explained.

Typical foods include a rice cake called a Bibingka and another type of rice cake, called Puto Bumbong, which is steamed in bamboo tubes and served with shredded coconut and brown sugar.

The most common Christmas decoration in the Philippines is the Parol, a large lantern in the shape of a star. People hang it outside their shops and homes, as well as in the town square.

“Having the Parol there rea l r e minds us of the star of Bethlehem,” Father Longalong explained.