PROSPECT HEIGHTS — When Hank Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the bottom of the 4th inning in a game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, the capacity crowd in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium rose to their feet, anticipating he would break Babe Ruth’s career home run record.

Sure enough, on the second pitch of the at-bat Aaron drove a fastball over the fence in left-center field. The stadium erupted. A couple of fans ran onto the field to congratulate Aaron while he rounded the bases. His Atlanta Braves teammates mobbed him at home plate. Soon after, he embraced his parents on the field, as adulation from the fans continued.

The whole time Aaron was smiling ear to ear.

Those scenes, however, are a far cry from what Aaron experienced off the field in the year ahead of the record-breaking moment. Aaron, a black man, received hundreds of thousands of death threats and hate mail from people not wanting a black man atop the record books.

In Aaron’s 1991 autobiography, “I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story,” he said that as he got closer to the record he felt he needed to break it not only for himself, for Jackie Robinson, and for black people, “but also to strike back at the vicious little people who wanted to keep me from doing it,” admitting also that all of the hatred left a “deep scar” on him.

“I was just a man doing something that God had given me the power to do, and I was living like an outcast in my own country,” Aaron wrote. “I had nowhere to go except home and to the ballpark, home and to the ballpark. I was a prisoner in my own apartment.”

“That whole period, I lived like a guy in a fishbowl, swimming from side to side with nowhere to go, watching everybody watching me. I resented it, and I still resent it,” Aaron continued. “It should have been the most enjoyable time in my life, and instead it was hell.”

Aaron was born on Feb. 5, 1934, in Mobile, Alabama. In his personal life, he married Barbara Lucas in 1953. They had five children together before they divorced in 1971. In 1973, he married Billye Aaron, who he had one child with, and who he was with until he died on Jan. 22, 2021.

Aaron has a history with the Catholic Church, albeit a complicated one. In 1959, Aaron, his wife, and their three children at the time were baptized at St. Benedict the Moor Church in Milwaukee. Eventually, though, Aaron joined the Baptist faith. It’s unclear exactly when this happened, but he was buried at Friendship Baptist Church in Atlanta.

On the diamond, Aaron debuted for the Milwaukee Braves on April 13, 1954, at 20 years old, about seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

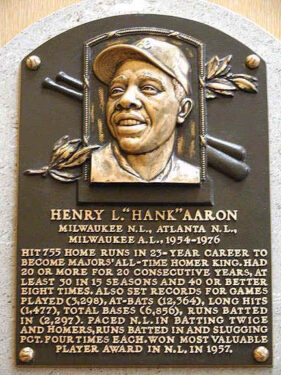

Aaron played for the Braves through the 1976 season, putting together one of the most accomplished careers in baseball history. Aaron finished his career with a .305 batting average. His 3,771 career hits ranks third all time. His 2,297 career runs batted in are the most all time. And his 755 career home runs are second only to Barry Bonds, whose career was tainted due to steroid use.

Aaron won the Most Valuable Player Award in 1957, when he batted .322 with 44 home runs and 132 RBIs. In his 23-year career, he played in 25 All-Star games — there was a stretch when baseball held two All-Star games in a single season to generate revenue. A career outfielder, primarily in right field, he also won three Gold Glove awards.

Aaron was elected into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982.

The racism Aaron endured and overcame, not only leading up to breaking Ruth’s record but throughout his career, has been well-documented over the years. But perhaps no one encapsulated the significance of what the moment represented better than legendary Dodgers’ voice Vin Scully did on his call in real time.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world,” Scully said.

“A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol, and it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron, who was met at home plate not only by every member of the Braves, but by his mother and father.”