by Michael Swan

TORONTO (CNS) – The Second Vatican Council was the biggest stage in the history of the Church.

There were more bishops present than at any of the 20 previous councils stretching from the First Council of Nicaea in 325 to the First Vatican Council in 1870. The bishops present came from more countries, more cultures, more languages than the Church had ever experienced.

While all of the bishops were equal, some were more influential. Joining them were expert theologians whom pre-eminent cardinals and bishops brought with them. Known as “periti” in Latin, the official language of the council, they played a significant role throughout the council’s deliberations.

Council’s Key Players

Here are a few of the names with starring roles at the council, which ran from Oct. 11, 1962, to Dec. 8, 1965:

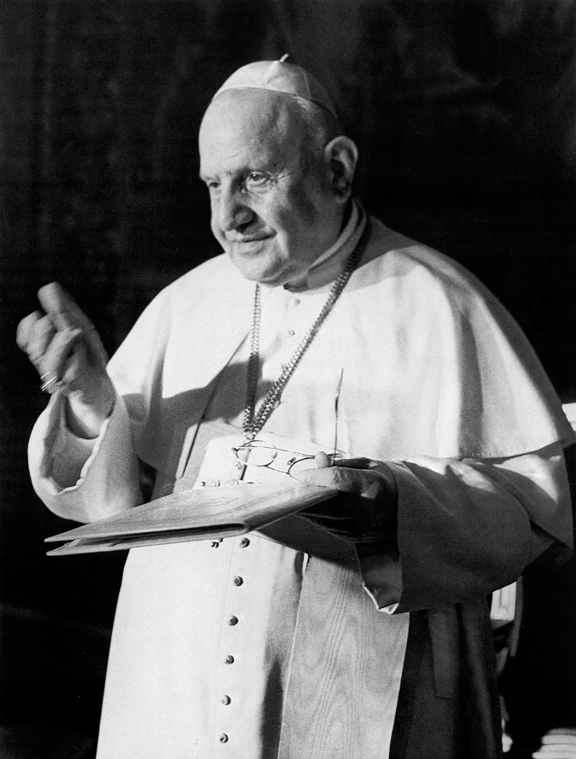

• Pope John XXIII: A plump, elderly, smiling Italian of peasant origins, Angelo Roncalli was supposed to be a caretaker after the long papacy of Pope Pius XII. He called the council and put the word “aggiornamento,” or updating, on every Catholic’s lips.

• Pope Paul VI: Cardinal Giovanni Montini began the council as a curial insider in the secretariat of state who had worked closely with Pope Pius XII. He had doubts about Pope John’s decision to call a council, but as his successor (he was elected pope in June 1963), he faithfully carried it to conclusion. During the council, he gave Mary the title of Mother of the Church.

• Cardinal Paul-Emile Leger: Montreal’s archbishop wrote a letter in August, 1962 to Pope John XXIII challenging the curial preparatory documents. The letter was eventually signed by a number of cardinals and archbishops, and the preparatory documents were reworked. He gave one of the council’s closing speeches in 1965. During the three sessions of the council, he argued for a stronger statement against anti-Semitism, greater Catholic commitment to ecumenism and a re-examination of Church teaching on birth control with more emphasis on love shared between a man and woman as the final purpose of marriage. Once considered a candidate for the papacy, he retired in 1968 to become a missionary in Cameroon.

• Cardinal Augustin Bea: Jesuit rector of the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome who eventually headed the Secretariat for Christian Unity was in the front line of defense against attempts by the Roman curia) to control the council agenda. A German, Cardinal Bea was deputized by Pope John XXIII to ensure the council said something bold on the Catholic relationship with Jews and world religions. The result was one of the most important documents, “Nostra Aetate” (“In Our Era”) on the relationship of the Church to non-Christian religions.

• Archbishop Dom Helder Camara: Head of the Archdiocese of Recife in Brazil’s dry, impoverished northeast who spoke for the poor and alerted the world to the idea that the Church was no longer a purely European phenomenon. Speaking for the world’s largest Catholic population in Brazil, he insisted on new priorities.

• Cardinal Josef Frings: The archbishop of Cologne, Germany, was an intellectual and a confidant of Pope John XIII who supported a role for theologians that counterbalanced the influence of the curia.

• Bishop Maxim Hermaniuk: As Ukrainian Catholic bishop of Winnipeg, Manitoba, he chaired the 15-member delegation of Ukrainian bishops to the council. He insisted that the Catholic Church was more than the Roman Church, and fought for the principal of collegiality through a permanent synod of bishops. He also insisted that the 11th century excommunication of the patriarch of Constantinople was not based on any Church teaching.

• Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani: A canon lawyer and prefect of the Holy Office (now called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), Cardinal Ottaviani’s view of the council was framed by his anti-communism and opposition to theological modernism. He was the council’s leading conservative.

• Cardinal Leo Joseph Suenens: The great conciliator, a friend of both Pope John XXIII and Pope Paul VI, Cardinal Suenens was once thought likely to be elected pope. It was the cardinal who ironed out a program that satisfied the concerns of both Cardinal Leger and Cardinal Ottaviani.

• Cardinal Eugene Tisserant: The French cardinal was the key to participation by bishops from behind the Iron Curtain. He negotiated a secret 1960 deal with Russia that allowed bishops to travel to the council in exchange for non-condemnation of atheistic communism. He was viewed as a conservative and a defender of the curia. He was also dean of the College of Cardinals.

The Experts

Here are some of the “periti,” or experts, who had a role at the council:

• Father Yves Congar: The Dominican expert in ecumenism was one of many theologians helping the bishops at the council who had been forbidden to publish or teach during the pontificate of Pope Pius XII. Father Congar offered one of the biggest ideas at the council: that the Church does not exist outside of history and Church teaching constantly must be restated in new ways to speak to new realities. He survived almost five years as a POW in World War II and was a major influence on Archbishop Karol Wojtyla, who as Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 1994.

• Father Henri de Lubac: A Jesuit silenced from 1950 to 1956, he was a prolific scholar associated with the “nouvelle theologie” (new theology) school. He promoted the idea of “ressourcement” at the council. Ressourcement is a return to the sources of Christian wisdom and a deepening of the Church’s understanding of itself, a movement that sought to retrieve Catholic teaching from the very earliest Christian communities and the desert fathers.

• Father Joseph Ratzinger: The future Pope Benedict XVI was closely associated with the nouvelle theologie movement. He was an expert for Cardinal Frings who wrote detailed critiques of the original curial schema for the council.

• Father Karl Rahner: This Jesuit’s ideas are everywhere in the council documents. His conception of the Trinity, the idea of anonymous Christians, the pilgrim church and his rejection of the counter-reformation practice of developing positions by condemning other positions helped shape Vatican II. It was Father Rahner who after the council pointed out that it was the first ecumenical council that was truly global, embracing a Catholic world beyond Europe.

• Father Gregory Baum: The German-born Canadian theologian worked with Cardinal Bea on “Nostra Aetate,” “Dignitatis Humanae,” the Declaration on Religious Freedom and “Unitatis Redintegratio,” the Decree on Ecumenism — the three documents that redefined the Church’s relation to non-Christian religions and particularly to Jews, its attitude toward democracy and religious liberty, and its mission for the unity of all Christians.

• Father Bernard Haring: The German Redemptorist taught how freedom of conscience was the necessary precondition for any meaningful morality. He was part of the commission which wrote “Gaudium et Spes,” the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World from Vatican II.