by Ezra Fieser,

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic (CNS) – Trinidad’s only Catholic seminary educated future clergy members for six decades, sending graduates to ministries throughout the Caribbean.

But by 2010, the Regional Seminary of St. John Vianney and the Uganda Martyrs had more staff than students and was losing nearly $100,000 a year. The Antilles Episcopal Conference closed it.

The seminarians were shipped to the Dominican Republic’s capital, where they were to finish their studies in Spanish – as opposed to the English spoken in Trinidad. Caribbean bishops promised to reopen the seminary in 2013 with a plan to shore up finances, boost enrollment and find more resident faculty.

The seminary’s closing, however, was emblematic of deeper challenges the Catholic Church faces in the Caribbean. While still the dominant religion, Catholicism’s influence has been waning here.

When Pope Benedict XVI arrives in the Caribbean in March on a historic trip to Cuba, he will encounter a region in a state of religious flux and economic uncertainty. The Catholic Church’s standing is being challenged by a rise in evangelicalism and a lack of indigenous clergy, as evidenced by the Trinidad seminary’s closing.

Add to those hurdles the region’s complex colonial history, the prevalence of Afro-Caribbean religions – such as Haitian Voodoo and Santeria – and widespread poverty.

“It’s a challenging environment,” said Archbishop Patrick Pinder of Nassau, Bahamas, president of the Antilles Episcopal Conference. “We’re talking about developing countries that are faced with post-colonial challenges … (including) the current economic crises.”

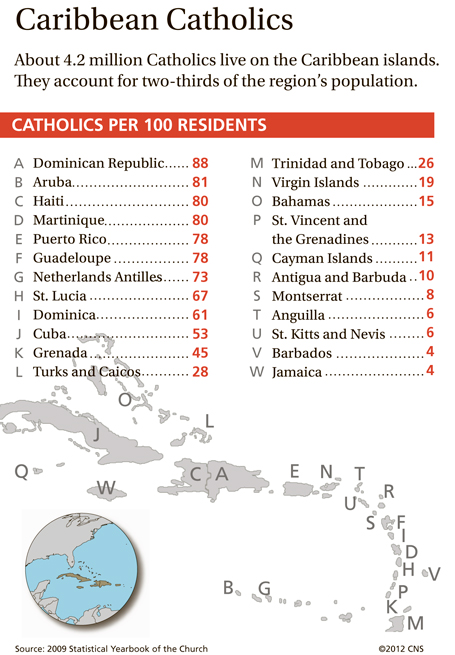

The Vatican’s statistical yearbook for 2009, the most recent available, lists the Caribbean as 65% Catholic, ranging from a high of 88% in the Dominican Republic to a low of 4% in Barbados and Jamaica. While that percentage is among the highest for any region in the world, estimates from previous years were as high as 78%, signaling a precipitous fall.

The change has been most pronounced in the eastern Caribbean, especially the English-speaking Caribbean. But the Spanish-speaking countries – Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and Cuba – also have been affected.

In the Dominican Republic, the second-most populated country in the region, evangelical ranks have grown to tens of thousands from being relatively nonexistent 20 years ago. The exact numbers are unclear because the government’s 2010 census, for the first time, did not capture religious affiliation.

But the influence of the evangelical churches is clear. Earlier this year, a group of evangelical churches successfully pressured the Dominican government to allow their ministers to legally oversee marriages, a right previously reserved for Catholic priests.

Cuba’s communist regime has long taken a hard-line approach to religion, declaring itself an atheist state in 1976, although it has since redefined itself as secular. Yet, the government has allowed an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 so-called home churches to spring up, which observers saw as a nod to the growing evangelical movement.

Due to their small size and minute populations, the changes are more dramatic in the Lesser Antilles, which ring the Caribbean Sea.

- Above, pilgrims arrive at the sanctuary of St. Lazarus in El Rincon, Cuba, Dec. 17. The annual pilgrimage to one of Cuba’s most sacred shrines draws thousands of Catholics as well as followers of the Afro-Cuban Santeria cult, for whom the saint symbolizes the deity of Babalu-Aye, a god who comforts and heals. Below, a Christian church made of wood is seen near the border with Haiti outside Loma de Cabrera, Dominican Republic, in this 2009 file photo. Caribbean nations have seen a growth in evangelical churches and followers over the last decade.

“You do see the Church losing members to the evangelical churches,” said Carmelite Father Gerard Tang Choon, who attended the Trinidad seminary and has preached in the country for eight years.

Two decades ago, Catholics made up 32.2% of Trinidad’s population, according to 1990 census figures. In 2010, the number fell to less than 20% of the country’s estimated 1.2 million people.

“We’ve seen a surge in numbers of small (evangelical) churches in recent years,” Father Tang Choon said. “A lot of Catholics who may be disenchanted … gravitate to the liturgies” of the evangelical churches.

The factors that have led to the rise in evangelicalism are directly related to the Catholic Church’s downturn, observers said.

Unlike Catholics, whose Masses are at the center of parish life, small evangelical congregations focus on pressing social issues like poverty.

“They can pray on everyday challenges; the issues that are important to them,” said Michelle Gonzalez Maldonado, assistant professor of religious studies at the University of Miami and co-author of the 2010 book “Caribbean Religious History.”

Leading those congregations are local residents familiar with the issues in the very communities in which they were born and raised.

“You see younger people who are coming to our churches because they are attracted to our style of worship,” said Clovis St. Romain, a laymen who is director of the United Evangelical Association in Antigua and Barbuda, small islands in the eastern Caribbean. “We can relate to their issues.”

St. Romain said the country has around 65 registered evangelical Christian congregations, with about 100 members each, and about 50 independent churches have sprung up in the past years. Ranks are growing by about 5% annually.

“It’s been the past 20 or more years that you’ve really seen the growth,” he said.

Meanwhile, Catholic churches have been forced to import priests, and there is still a shortage.

Despite Irish, French and Indian priests brought in to fill the gap, Father Tang Choon celebrates about five Masses every weekend.

“It’s a stress on younger priests,” he said. “And it’s not an attractive lifestyle for younger people who are considering a life in the clergy.”

It’s also a cycle that has hurt the Catholic Church’s ability to attract young people. When Father Tang Choon finished at the seminary in the early 2000s, his class size was about a dozen and made up of students from various islands.

When the seminary closed in 2010, only five students remained, he said.

Archbishop Pinder said attracting young people to the church and improving the ranks of homegrown clergy are related. The Church needs to keep its message on social justice and continue its work in education and health care, he said.

The archbishop was born and raised in Nassau and promoted to archbishop in 2004. He knows, however, that his case is rare.

The lack of local clergy “is an issue that’s been there for quite a while,” he said. “I think the key to addressing it starts with strong Catholic families and young people.”

Father Tang Choon remembers feeling a sense of validation for the Trinidad church when Pope John Paul II visited the country in 1985.

“I was 11 or so, and I remember there was a huge amount of energy and enthusiasm around the visit,” he said.

Although Pope Benedict is only scheduled to visit Cuba, his trip could provide an opportunity to reclaim lost ground in the Caribbean.

“I have no doubt about the strategic nature of the pope’s visit to Cuba,” Gonzalez said. “It’s part of the Church’s effort to reclaim Cuba and reclaim its stake in the Caribbean.”