Even without reading any of the pages in David Brooks’ “The Road to Character” (New York: Random House, 2015, $28, pp. 300), the titles of Brooks’ 10 chapters might convince a possible reader that the book is special.

The titles of the 10 chapters are: “The Shift,” “The Summoned Self,” “Self-Conquest,” “Struggle,” “Self-Mastery,” “Dignity,” “Love,” “Ordered Love,” “Self-Examination,” and “The Big Me.”

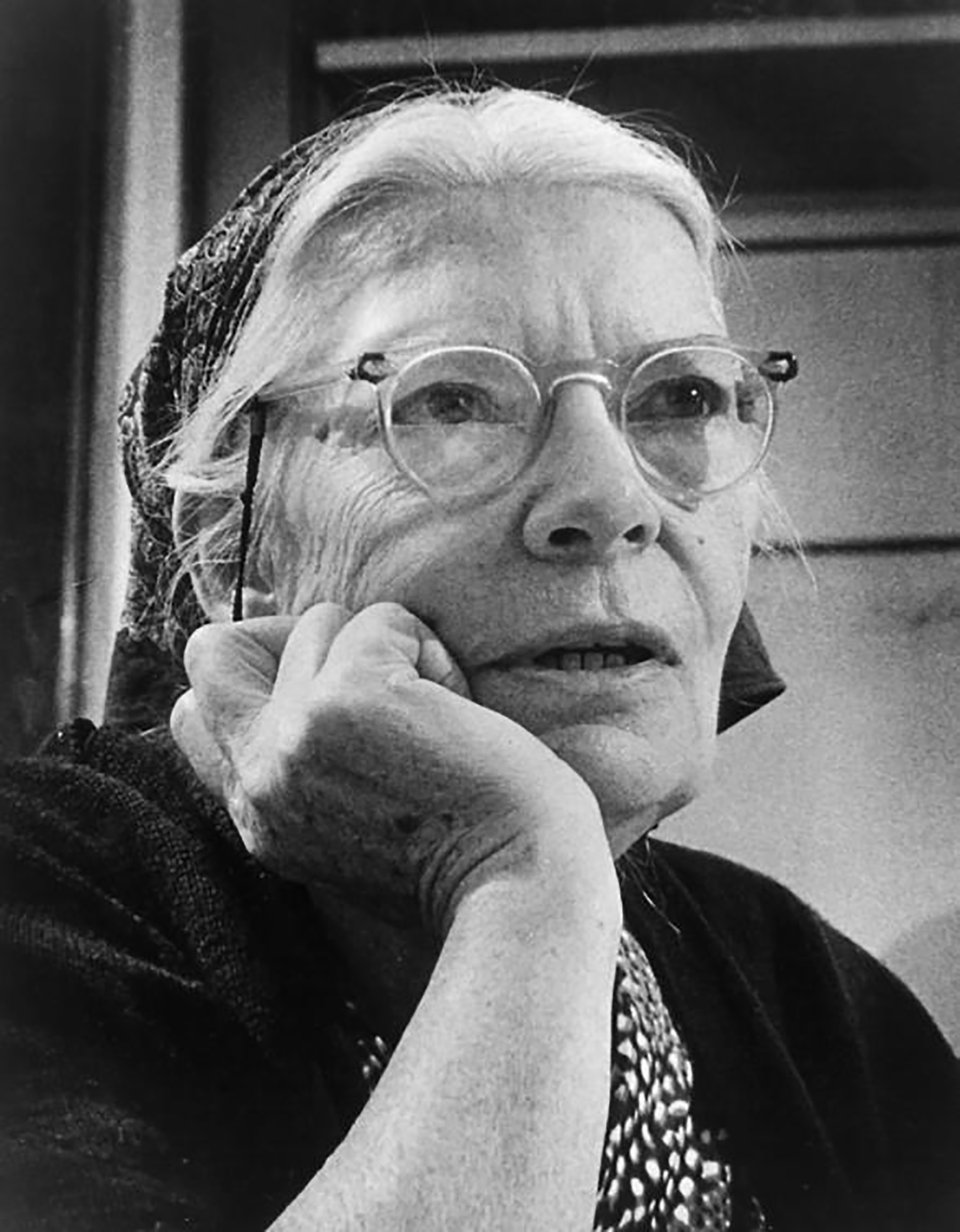

One of my favorites is chapter four, titled “Struggle,” in which Brooks uses Dorothy Day, co-founder of The Catholic Worker, as an example of outstanding moral character. Some think Day was the most influential American Catholic of the 20th century. I thought I knew Dorothy Day fairly well, having read about her and also her own writings, in addition to meeting her over at the Catholic Worker House of Hospitality on the Bowery in New York City. However reading Brooks’ chapter, I learned more.

Impacted by Storm

At the beginning of this chapter, Brooks tells of an eight-year-old Day having an extremely powerful experience during the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Alone in the house during the storm, she experienced the power of the storm as related in her mind to a powerful God, an impersonal God. When the storm subsided there was a wonderful experience of people pulling together after the storm. Decades later, Day wrote in her memoirs that while the crisis lasted, people loved one another. She wrote: “It was as if they were united in Christian solidarity.”

One writer, Paul Elie, thought that the experience of the earthquake – and people helping one another after it – prefigured Day’s later life. Brooks writes the following:

“Day was born with a passionate, ideal nature. Like Dorothea, the main character in George Eliot’s novel ‘Middlemarch,’ her nature demanded she live an ideal life. She was unable to be satisfied with mere happiness, being in a good mood, enjoying the normal pleasures that friendships and accomplishments bring. … Day needed spiritual heroism, some transcendent purpose for which she could sacrifice.”

Who can guess how many thousands of people Dorothy Day’s commitment and example have influenced?

I remember vividly the first time I met Day though it took place more than 60 years ago. There was a lecture at The Worker, which was a Friday evening practice that continues to this day, and the speaker was a priest from France who worked with the poor. In the question-and-answer period, a man rose, ostensibly to ask a question. I don’t know what his point was or even if he had a point. He seemed to be emotionally disturbed and made little sense.

While he was speaking, I looked over at Day. Her body language and facial expression suggested that she was listening to Thomas Aquinas or some other genius. Her presence to that questioner made a strong impression on me. I have thought of it many times and it probably has helped me be a little more patient with people who may be speaking, but seem not to be making any sense. If each of us had that kind of reverence and respect for one another, then Pope Francis’ revolution of tenderness would happen.

I wonder if Brooks’ description of Day as someone who “needed spiritual heroism” might fit a number of people who have been very dedicated Christians. I think immediately of Mother Teresa, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton. I suspect that I am wrong, but I have difficulty imagining any of these people engaging in small talk. Perhaps exceptionally dedicated people pay for their dedication in having difficulty with normal interpersonal relationships that others have no difficulty in forming. I will leave it to psychologists to figure out what type of temperament and personality deeply committed people and exceptional leaders of special causes have. People who are great leaders may be people who are not easy to live with just because they are so different from the so-called “average person.”

The following is Brooks’ suggestion of why Day was such an inspiring religious leader:

“…her hunger for the poor, her capacity for intense self-criticism, her desire to dedicate herself to something lofty, her tendency to focus on hardship and not fully enjoy the simple pleasures available to her, her conviction that fail as she might, and struggle as she would, God would ultimately redeem her from her failings.”

Day’s vision and commitment to the poor is present today in those involved with The Catholic Worker. I still find that commitment and vision inspiring.

—

Father Robert Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica, and author of “Pope Francis’ Spirituality and Our Story” (Resurrection Press).

This photo is not by CNS. It was taken by a Milwaukee J0urnal photographer when Dorothy visited Milwaukee in February 1968.

Thank you for reading The Tablet. You are correct, this photo is taken my the Milwaukee Journal. But we bought it as part of a copy righted package from CNS. Which means that CNS bought copy righted distributing rights or at least they made some kind of deal to retain them. We don’t have the right to this picture directly. We have the right to this picture from our paid subscription to CNS. Therefore we have to credit CNS, but we do mention that that they obtained it from Milwaukee journal. That’s why we give them the courtesy line: Photo © CNS/courtesy Milwaukee Journal. I know, confusing.