On Pointe: From Harlem To Broadway

JAMAICA — Frances Rhymes rubbed elbows with the likes of Frank Sinatra, Alvin Ailey, and Michael Jackson over the years, but her favorite place in the world is not some star-studded Hollywood party. She’d rather be in church.

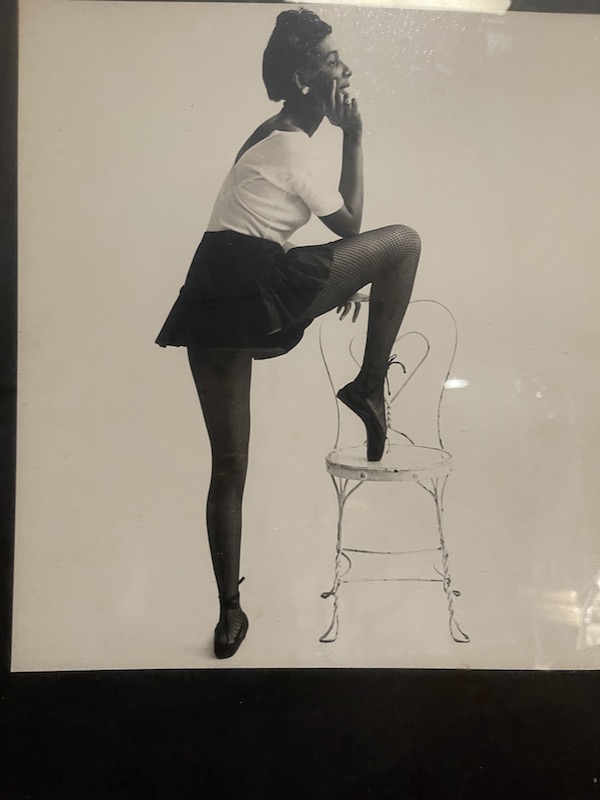

Rhymes, 90, a retired professional dancer who toured the country with the Katherine Dunham Dance Company in the 1950s, appeared in two Broadway shows, and hobnobbed with celebrities, is a parishioner at St. Bonaventure-St. Benedict the Moor Parish in Jamaica and attends Mass every morning.

“I’m so very grateful for the life God has given me,” she explained. “I love to go to church to show Him that gratitude.”

She started a dance school in the early 1960s — the St. Benedict School of Dance — to teach children the joy of movement and the importance of poise and posture.

The school, which is now called Rhymes Lowery Dance Theater Arts Guild, operates every Saturday out of the church hall at St. Benedict the Moor. Rhymes runs the program with her daughter, Terri Rhymes-Lowery.

On a recent Saturday, after Rhymes-Lowery taught a class some new dance steps, Rhymes offered the youngsters a bit of her wisdom. “I don’t look 90. Why? Because I danced,” she told them. “Keep trying to do your best, and you’ll go places.”

Rhymes has great memories of her life as a dancer — the thrill of appearing on Broadway, the joy of receiving standing ovations, and the camaraderie she enjoyed with fellow performers — but she also saw, up close, the evils of racism in 1950s America. However, she also saw how to fight back.

She recalled one time when Dunham, the world-famous black dancer-choreographer, wanted her dancers to audition for a show. But Dunham was told by the producers that they weren’t willing to consider hiring her dancers because they didn’t have the right look. The producers explained they were looking for blonde dancers. In response, Dunham took an unusual step.

“She went out and bought blonde wigs and sunglasses for all of us. And she asked them, ‘Now, can they audition?’ She was a strong woman,” Rhymes recalled. The Dunham dancers didn’t get to audition that time, but the legendary choreographer had made her point.

Mention Frank Sinatra’s name to Rhymes, and she smiles. “Old Blue Eyes” took a stand against racism in a hotel in Reno, Nevada, by confronting a hotel manager, she said.

Sinatra was the headliner at a local nightclub, and the Katherine Dunham Dance Company was on the bill. “We weren’t allowed to stay in the hotel. We had to sleep on the bus,” she recalled.

When Sinatra got wind of this, he invited the entire Dunham troupe to stay in his suite, Rhymes recalled. The hotel manager told him the dancers couldn’t stay, at which point Sinatra threatened to go elsewhere. “He said, ‘If these folks aren’t good enough to stay here, then I’m not good enough, either.’ The hotel changed their mind,” Rhymes said. “I’ll always remember him for that.”

Looking back on her life, she realizes she was always meant to be a dancer. She was born Kay-Frances Ann Taylor in Harlem on April 22, 1932. At the age of 6, while playing in the park, she was approached by the park’s activities director, Ruby Magby, who invited her to take dance lessons. Magby had been a dancer in the famous Cotton Club in Harlem. It was in Magby’s class that young Kay-Frances fell in love with dance.

When she turned 8, she received a scholarship to study dance with Jerry LeRoy, a respected dance instructor in Midtown. Ten years later, at age 18, she began studying under Katherine Dunham and became a member of her company, touring the country. By this time, she had dropped Kay and was going by the name Frances.

“I learned the Dunham Technique,” she recalled, explaining that the choreographer included traditional African movements in her modern dance pieces.

Taylor was a dancer in the Broadway show “The House of Flowers” in 1954. Alvin Ailey, who would go on to found the world-famous Alvin Ailey Dancers and become an influential choreographer, was also in the cast. “My mother knew Alvin Ailey before he was Alvin Ailey!” Terri Rhymes-Lowery said.

While Broadway was a thrill, in Rhymes’s mind, it didn’t compare to being onstage at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. “That was one of the greatest joys of my life,” she said.

Backstage, she met people like Nat King Cole and Sarah Vaughan. “They didn’t act like big stars. They were down to earth. We were all just performers, performing for the people,” she remembered.

It was another Broadway show, “Mr. Wonderful” in 1956, that changed her life. She met her husband, Clyde Anthony Rhymes Jr., a singer in the group called “The Rhythm Aces,” who was also in the cast.

They were married in 1956 and bought a house in Jamaica, Queens. While taking a walk one day, she came across St. Benedict the Moor Church.

Rhymes was born and raised a Baptist but was looking to convert because she felt the Baptist church no longer spoke to her. She met with a priest and was baptized into the Catholic faith.

She was an active parishioner, founding St. Benedict’s School of Dance and serving on the parish council. Over the years, she has taught generations of young people not just how to dance but how to respect themselves and their bodies.

Her motto is, “Always stand up tall. You do not have to be a model to look like one.”

Rhymes turned her talents toward choreography and founded her own troupe, the Frances A. Rhymes Dance Company, which performed with other dance companies like the Dance Theater of Harlem in places like the Apollo, The Kennedy Center, the Waldorf Astoria, and the United Nations.

Her career as a choreographer put her in touch with a future superstar — Michael Jackson. She showed him a few dance moves when he was the headline performer in a show at the Coconut Grove nightclub in Hollywood in 1978. She remembers him as a shy, quiet, and soft-spoken young man.

These days, she enjoys going to church. “I try to do my best to live my life as a good Catholic,” she said.