PROSPECT HEIGHTS — In 1878, yellow fever swept the lower Mississippi Valley, bringing chaos and killing an estimated 5,000 people in Memphis, Tennessee.

The viral infection wrought debilitating headaches, internal bleeding, organ failure, and septic shock. The fever decimated the city’s police force. Lawlessness and violence grew, and many residents fled.

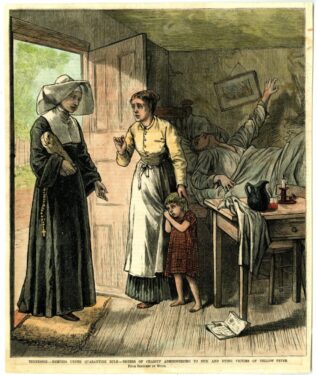

But the Dominican friars of St. Peter’s Catholic Church stayed. They comforted and cared for the dying, many of them Irish and German immigrants.

Illuminating their nighttime forays was their lantern-toting church handyman — the former slave Samuel Henderson. All risked infection and anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant prejudices, but Henderson, a convert to Catholicism, also faced a simmering hatred against freed people.

“Quite frankly, Memphis was not a great place to be a black man, much less a black Catholic,” said Morris Butcher, a resident of the city who has written about Henderson. “He chose the most dangerous option: to take himself out of the frying pan and throw himself into the fire.”

While none of the 11 saints associated with the United States are black, there are six black Catholics, known as the “Saintly Six,” whose lives and work have set them on a path toward canonization — Venerable Pierre Toussaint, Venerable Henriette Delille , Venerable Augustus Tolton, Servant of God Mary Elizabeth Lange, Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman,, and Servant of God Julia Greeley.

Butcher, an engineer, is also the master of ceremonies at St. Peter’s Church. He said Catholics in Memphis are discussing how to promote Henderson to sainthood consideration. However, a cause for Henderson has yet to be opened.

“The Church in that period was often very unfriendly to African Americans,” Butcher said. “Segregation continued in lots of places on top of that. This is the same era when Augustus Tolton couldn’t get a job as a priest.”

“But there is just something about the story of [Henderson] choosing to do what he saw as his duty, to follow these friars into certain death, night after night,” he said. “On top of that, the parish adopted Sam as their own.”

Father John Vidmar, a modern-day Dominican friar, covers this time in his 2020 book, “Bury Me in the Sunshine: The Yellow Fever Epidemics of Memphis,” which describes the friars’ heroic responses and how some of them also died.

Father Vidmar is a history professor at Providence College in Rhode Island and the author of several books. He said that, like all Dominican heroes in Memphis, Henderson is also worthy of consideration for sainthood because he risked his health and safety to help the friars ensure that those who died were cared for with dignity.

And when a Dominican died, Henderson extended the same dignity to them.

“He dressed our men in their caskets,” Father Vidmar said.

Father Vidmar said he discovered Henderson’s story while researching a term paper about the Dominicans’ response to Memphis’s yellow fever horrors.

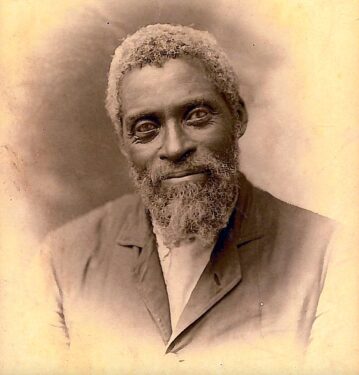

“I was in our provincial archives when I found a photograph of him,” he said. “It’s an amazing photograph.”

The image is unlike many stoic portraits from that time. Henderson offers a slight smile, a humble head tilt, and soulful eyes beaming joy.

“When I saw that picture I thought this looks like the kindest person I’ve ever seen,” Father Vidmar said.

He dug further into the former slave’s story while researching his book, “Bury Me in the Sunshine.”

Henderson, born around 1827 in Tennessee, came to Memphis as a free man looking for work after the Civil War. There is no other information about his youth, although he reportedly had a wife. History does, however, show that Henderson was a man of God who led a small congregation of black Baptists in a church near St Peter’s.

Father Vidmar said Henderson routinely attended the Catholic Mass. Then, he preached what he heard in the homily to his congregation of Baptists.

Later, St. Peter’s hired Henderson to maintain the church, which was designed by the famed Brooklyn architect Patrick Keely. Father Vidmar said at some point Henderson thereafter Henderson converted to Catholicism.

Memphis experienced several yellow fever epidemics in the 1800s, but the one in 1878 was the deadliest. Federal troops formed a blockade around the city to stop people from fleeing and spreading the disease elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Father Joseph Kelly, pastor at St. Peter’s, argued with city leaders who wanted to shut down public gatherings, including religious services, similar to the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, Father Vidmar said, the pastor kept celebrating Mass until he got sick. After two months, he recovered and resumed celebrating Mass and started an orphanage for children of fever victims.

Father Vidmar said the friars worked with religious brothers and sisters, priests from other parishes, and heroic clergy from the Episcopalian and Jewish faiths.

Many clergy and religious, however, contracted the virus. “We lost eight Dominican priests,” Father Vidmar said. “Sixteen Dominican sisters died out of a total of about 22 sisters involved. Franciscan sisters also suffered very heavily.”

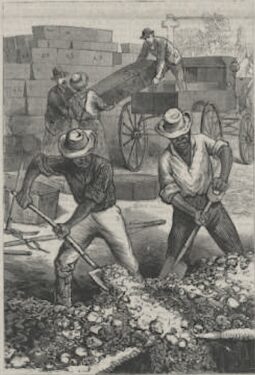

Conversely, there is no record of Henderson being sick. The virus reportedly came to the United States on slave ships, and then mosquitoes helped spread it. But Henderson could’ve had ancestral immunity, Father Vidmar said. While some former slaves did become sick, he noted, only 7% of them died, while the white patients had a 70% mortality rate.

“So, they obviously were going to use the African Americans in grave digging,” Father Vidmar said.

Henderson, however, seized upon a special mission.

The friars ordered him not to accompany them on their sick calls, but he refused out of fear for their safety and lit his lantern. Sometimes, he hung back in the shadows but still followed to make sure they returned safely to their priory, Father Vidmar said.

When friars got infected, Henderson stepped up again.

“He would nurse them,” Butcher said. “And then, if they died, he bathed them and prepared them for their funerals.”

When Henderson died in 1907, he received a solemn Requiem Mass celebrated at the high altar inside the filled-to-capacity St. Peter’s church. Eight Dominican friars were the pallbearers. “It’s amazing, “Father Vidmar said. “And then they paid for his monument in the cemetery.”

Henderson’s stone inscription is, “Here Lie the Remains of Samuel Henderson, St. Peter’s Sam.”