BEDFORD-STUYVESANT — In 1915, a group of black Catholics met at a home on Pacific Street in Prospect Heights, across from what is today the Co-Cathedral of St. Joseph. The Spanish Colonial-style church with two bell towers was completed just three years earlier to replace the previous parish church, which was built in 1861, the same year the American Civil War began.

Although slaves were freed as a result of the war, these 25 black Catholics did not feel welcome at the new building or any other place of worship in Brooklyn, which at the time was nicknamed the “City of Churches.”

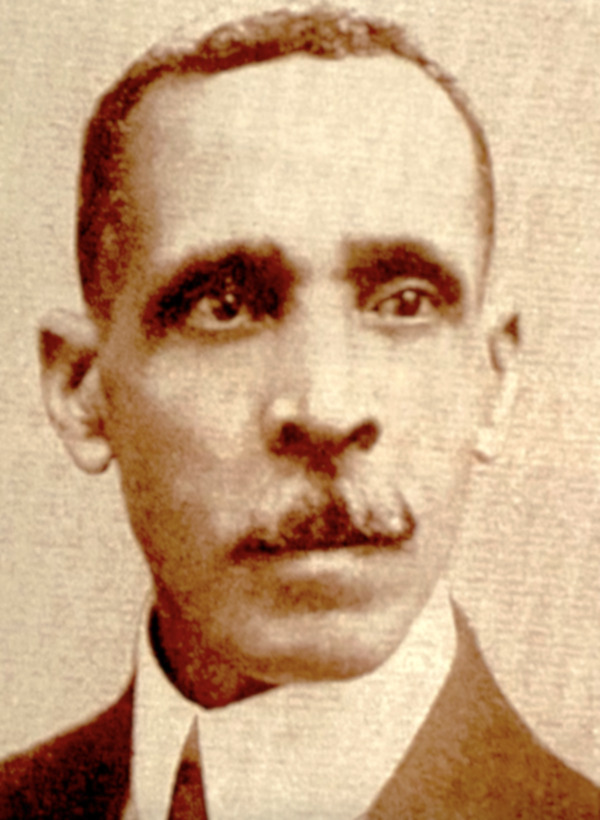

Jules DeWeever, 44, convened the group to strategize a “church for colored Catholics established in this diocese,” according to notes from that meeting. Meanwhile, a priest of Irish heritage, Father Bernard Quinn, 27, was lobbying for the same thing.

Working without knowing each other’s efforts, DeWeever and the future Msgr. Quinn faced setbacks. However, after the priest returned from World War I, the two finally met and established the first congregation for black Catholics in the Diocese of Brooklyn — St. Peter Claver Parish in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

While Msgr. Quinn is now a candidate for sainthood because of his humanitarian service to African Americans, the president of the guild that is promoting his cause for canonization also wants DeWeever remembered.

“[DeWeever] should not be forgotten,” said Delores Casey of Brooklyn, president of the Father Bernard John Quinn Guild. “In learning about him, you learn about Father Quinn. They’re connected. He’s part of the big picture.”

DeWeever, born in 1871, immigrated with his family from the Dutch West Indies as a child. He spent his adulthood working for the U.S. Postal Service. Although the exact year he came to Brooklyn is unclear, his arrival no doubt coincided with a significant influx of black people in the late 1800s.

Many, like DeWeever’s family, were from Caribbean nations, while others came from Southern states looking for opportunities as racial discrimination persisted in the South after the Civil War and intensified with “Jim Crow” laws in the 1880s. However, racism also thrived in the North.

Brooklyn had one of the harshest slave codes in North America until the state abolished slavery in 1827. And until emancipation for the rest of the nation, bounty hunters could legally prowl throughout New York looking for people who escaped on the Underground Railroad.

Casey said lingering resentments persisted, and black Catholics were not welcome in local churches. Consequently, she explained, black Catholics in Brooklyn had to cross the East River to attend the welcoming St. Benedict the Moor Parish, then on Bleeker Street in Lower Manhattan. Father Augustus Tolton, the first black Catholic priest ordained in the United States, celebrated his first Mass there in 1883.

It was a situation similar to the dilemma of Irish Catholics in Brooklyn who crossed the river by ferry to attend Mass at St. Peter’s Parish, also in Lower Manhattan. That continued until the Diocese of Brooklyn was formed in 1853.

When the Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883, it added another transportation option, but DeWeever and his committee resolved to find a solution for fellow Catholics who wanted a parish near their homes.

Their group, known as the “Colored Catholic Club,” or CCC, petitioned Bishop Charles Edward McDonnell for a black Catholic parish, but the document “became lost or overlooked,” according to Casey.

Meanwhile, new parishes were popping up all over Brooklyn and Queens to accommodate influxes of Irish, German, and Italian immigrants. The setback dismayed the group, and it disbanded in 1917, but Casey noted that DeWeever refused to give up.

As he struggled to figure out his next move, Msgr. Quinn wrote to Bishop McDonnell to request a mission church for black Catholics. Msgr. Paul Jervis, who died in 2023, wrote about this in his book, “Quintessential Priest, The Life of Father Bernard J. Quinn.”

Msgr. Jervis, a former pastor at St. Peter Claver Parish, also wrote about Msgr. Quinn for The Tablet. In a 2019 article, he described being “flabbergasted” that the priest, as a young man, befriended black children and treated them kindly.

Born in Newark, Msgr. Quinn learned from his family about discrimination against Irish Catholics. He was dismayed when black Catholics felt “invisible” to Church leaders, Msgr. Jervis wrote. He also volunteered to serve mission churches in the South after Bishop McDonnell requested local priests to help.

That plan, however, was scrapped in 1917 when the United States entered the “Great War” in Europe, and it was up to Bishop McDonnell to offer priests from his diocese to serve as military chaplains. Msgr. Quinn answered that call, too.

In 1918, he was in France, ministering to “doughboys” of a machine gun battalion in the 86th Infantry Division. He returned to Brooklyn in 1919, although his lungs were severely damaged by mustard gas, which plagued him for the rest of his life.

Claver Parish in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

In 1920, he renewed the request to start a mission church for black Catholics. This time, Casey said, the bishop agreed. The diocese, however, had one recommendation — locate a postal worker named DeWeever, president of the disbanded CCC, who could link the priest to the black community.

In “Quintessential Priest,” Msgr. Jervis included Msgr. Quinn’s own written recollection of what happened next. He telephoned an acquaintance at the post office, who arranged a meeting between the priest and DeWeever.

“This was a real God-send,” Msgr. Quinn wrote in a church bulletin included in Msgr. Jervis’ book. “Mr. DeWeever brought me the books containing the list of members of the Club. I wrote a letter to each one of them. This was 1920. Four years had elapsed, and many on this list had moved. But those who received my letter responded cheerfully.”

“Together,” Msgr. Jervis wrote in The Tablet, “they went about raising money for the establishment of their church.” A lasting friendship followed. Casey said DeWeever was “regenerated” by the work. “He was very, very excited,” she said. “Now he had a priest that was not assigned — this was a priest who wanted to do this. That’s the difference.”

After purchasing a dilapidated, former Protestant church, Msgr. Quinn had the building restored. It was dedicated as St. Peter Claver Parish by Bishop McDonnell on Feb. 26, 1922, Msgr. Jervis wrote.

Msgr. Quinn’s work continued; he built orphanages for black children on Long Island and rebuilt them after arson attacks by the Ku Klux Klan. He also created other black parishes, like St. Benedict the Moor in Jamaica, Queens.

DeWeever, meanwhile, stayed faithful to Msgr. Quinn and, together, they formed an active lay apostolate of black Catholics. DeWeever also chaired the St. Vincent de Paul Society at St. Peter Claver Parish for more than 20 years.

DeWeever and Msgr. Quinn both died in 1940. The pastor was 52. DeWeever was 69.

In his book, Msgr. Jervis pointed to a 1953 article in The Tablet that noted DeWeever “became well known for exemplifying the spirit of the selfless devotion of the Society towards the poor.” “His charitable work in providing emergency assistance to countless numbers of people became legendary,” he wrote.

Wow! what a precious information! It enriched my knowledge of Msgr.Quinn’s story of the Blacks Community of Brooklyn of which I was acquainted before from Msgr. Jervis, the late Pastor of my Parish, St. Francis of Assisi/St. Blaise in Brooklyn. That article, somehow, from my point of view, will bring a”Boost” to the Cause of Canonisation of Msgr.Queen of which Msgr.Jervis was such an ardent promoter!

Thanks again,

Gilberte M. Verna,

reader of the Tablet.