By Agostino Bono

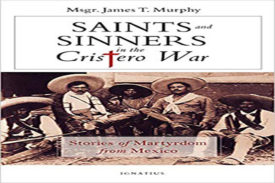

“Saints and Sinners in the Cristero War: Stories of Martyrdom from Mexico” by Msgr. James T. Murphy. Ignatius Press (San Francisco 2019). 286 pp. $17.95.

Mexican Catholicism is symbolized by the positive image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the country’s patroness. The image recalls the Dec. 12, 1531, appearance of Mary to a native of the New World, her indigenous features encapsulating the desire to infuse Catholicism into Latin America’s native populations. Mexico also is the world’s second largest Catholic country, population wise.

Yet Mexico’s Catholic history also has its dark side, sometimes deeply painted in blood. The country’s faithful faced decades of repressive anti-clerical governments from the second half of the 19th century until well into the 20th century. During this time Mexico’s government leaders were strongly influenced by the Enlightenment and French Revolution making anti-clericalism a cornerstone of politics. Bishops were forced into exile. Priests had to register with the government. Church buildings were confiscated. A Catholic education system was prohibited.

Perhaps the most dramatic event was the 1926-29 Cristero War, a grassroots rebellion by rural ill-equipped but strongly motivated Catholics. It was David vs. Goliath, with sandal-footed farmers facing the well-trained and armed Mexican army. When it started few predicted the rebels would last more than a few months. Instead, the war dragged out for three years and the Cristeros actually held and administered swaths of rural areas.

The book notes that they could have controlled more were it not that many of the farmer-fighters didn’t want to wander too far from home so that they could regularly visit their families and get a good meal. Many refused to fight during the harvest season because they would lose their crops.

The men were aided by women who not only encouraged their brothers and husbands to fight but also used guile and money to buy ammunition from corrupt soldiers to pass along to the Cristeros.

The term Cristero comes from the soldiers’ battle cry, “Viva Cristo Rey,” Spanish for “Long live Christ the King.” In 2000, St. John Paul II declared as saints 25 Catholics martyred during the fighting.

But this book is more than a war chronicle. It dissects the religious, social and political aspects of Mexico’s anti-Catholic history. It is also excellent in describing the nuanced, complex negotiations involving the Mexican government, the bishops and the Vatican to end the war and water down Mexico’s legal anti-Catholicism. Mediating these negotiations was the U.S. government aided by a U.S. Jesuit priest.

The author, Msgr. James T. Murphy, a journalist, is scrupulous in presenting balanced reporting. Now retired, he was the director of communications for the Diocese of Sacramento, California, and managing editor of its newspaper. Although the book’s title refers to “saints and sinners,” he shows that not everyone who fought with the Cristeros was saintly. Some ex-priests who took up fighting were corrupt and womanizers. And not all the anti-clerical leaders were without political virtue as they promoted many programs compatible with Catholic social teachings.

Actually, few of the 25 saints canonized in 2000 are mentioned in the book. More time is spent on the nuanced and diverse approaches used by Catholics to fight the anti-clericalism in keeping with their individual moral consciences. The author notes that many Catholics, while opposing the government’s anti-clericalism, did not join the rebels in part because they supported major government efforts to improve the economy, health standards and the transportation system to the benefit of the general population.

The book also notes how the war forced major soul-searching among the clergy regarding how to support the rebellion. In general, bishops opposed taking up arms, favoring an underground church in which clergymen in disguise celebrated Masses and performed the other sacraments in secret in homes, abandoned buildings and secluded rural areas. Many priests also served as noncombatant chaplains to the Cristeros as their bishops turned a blind eye.

The book is a tribute to the strong faith and tenacity of Mexican Catholics who kept their belief alive whether as warriors or nonviolent resisters.