RICHMOND HILL — A Queens-born writer harkens back to the borough that brought America Archie Bunker, The 1969 baseball champion New York Mets, and The World’s Fair.

While many in the neighborhood looked for the greener lawns of suburbia in the early ’70s one Italian family stayed, and they’re still there.

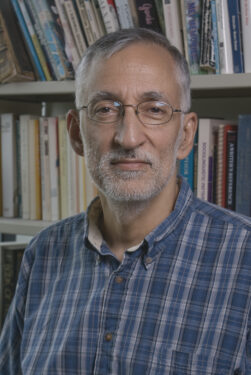

Author Joe Benevento, an English professor at a Missouri university, described how his novels and poetry spring from the story of his youth — spent as one of seven children of an Italian-American family in Richmond Hill.

His parents, Mary and Joseph Benevento, battled poverty with hard work and an unwavering Catholic faith nourished by their parish, St. Teresa of Avila. After raising four daughters and three sons, they continued living in their house on 130th Street until their deaths, both in their early 90s. Two of Benevento’s sisters reside in the house today.

Benevento shares glimpses of this loving home in fiction and poetry. His Catholic upbringing also informs other works. His next novel, “My Perfect Wife, Her Perfect Son,” explores the challenges and joys of St. Joseph. It’s due out in early 2023.

“Queens, Catholicism, and religion have been a big part of a lot of the fiction I’ve written,” he said. “But I’m as much a poet as a fiction writer. I’ve had seven books of poetry published, and probably more than half of them are just memories of the old neighborhood and growing up there.”

‘Our Parents Were Saints’

Benevento lives with his family in Kirksville, Missouri, where he teaches at Truman State University. The college town is a stark contrast to growing up in “working class” Queens, he said. As a boy, his family was very religious, industrious, and frugal.

“We never went out to a restaurant,” Benevento said. “My mother thought that’s crazy. She’d say, ‘I can make better food here.’”

His older sister, Rose Anne Alafogiannis of Astoria, agreed.

“She used to make her own ravioli and her own bread,” she said. “And nobody could make a better pizza than my mom. Forget about it. We thought we were in seventh heaven, but it is what she did to save money.”

Meanwhile, Alafogiannis said, their father worked multiple jobs.

“He was in construction and, in the winter, they didn’t really work that much,” she recalled. “So he worked every other job imaginable, just so we wouldn’t have to go on welfare or aid.”

But the family wasn’t stingy. Benevento and Alafogiannis recalled how their parents took in the baby boy of an unwed Greek woman abandoned by her fiancé. She worked long hours as a waitress.

“And then my mother said, ‘This is crazy. Why don’t you just live with us too?’” Benevento said. “‘That way, you can be with your baby more.’ They lived with us for six or seven years before she eventually moved back to Greece.”

Said his sister, “Both our parents were saints.”

In his poem, “Stay-At-Home Dad,” Benevento wrote this of his father:

By the time he could retire from

his maintenance job, he was 73;

Mom was too sick to travel,

and he’d not go anywhere without her.

So, aside from an occasional

bus trek with the other seniors

to lose some quarters in Atlantic City,

he’s been stuck in working-class Queens.

He never will get to Colonial Williamsburg (history buff),

Calabria (where his parents were born), nor even

Chicago. At 89, cane-reliant diabetic, my poor

father, after life’s long labor, stays at home,

though he’s with me

everywhere I go.

‘Edgar Allen Joe’

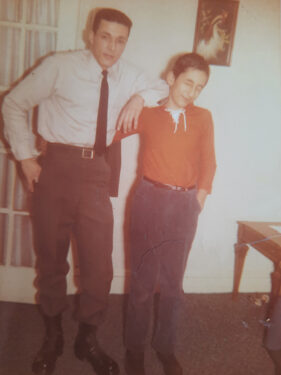

Although money was tight, the Benevento children had lots of fun.

“When we weren’t playing touch football, we were playing basketball in the park,” Benevento said. “And in the evening, we’d run around and play tag or whatever. And then when it got dark, we’d sit around and tell stories.”

On the three-step stoop of his home, before a front-yard shrine with a statue of Mary, Benevento, a fan of Edgar Allen Poe, earned the moniker “Edgar Allen Joe” for the scary stories he’d conjured up.

For example, his shady character named the “Black Banana” prowled the neighborhood at night, looking for victims.

“Once my friend Jose Ramos was walking home in the dark and he saw a dark figure headed his way and got really scared that he was about to encounter the ‘Black Banana,’” he said. “But it actually ended up being my dad, getting home late from work after overtime.”

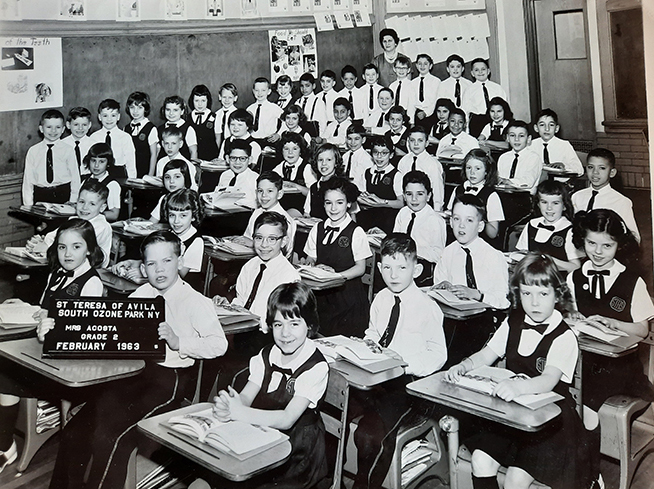

Benevento wrote his first poem in the 4th grade at St. Teresa of Avila School. Later, he attended high school at Cathedral Prep and Seminary while considering the priesthood.

Life was not all frivolity. For example, “After the Boys Goaded Me and Ricky Irizarry into a Fistfight” expresses his shame of giving in to violence. It reads, in part:

… with more drama than any overtime, framed us into hitting

each other’s faces, our winter gloves the only cover for

our bare fists, our lack of skill or style no stop to the joy

our pals procured, seeing their two backup centers contend

way harder than we ever managed on the court. I fought furious,

my rage making me immune to the hard shots I received,

caught up in all the things I hated, none of them named

Ricky Irizarry, so when they took us under the Parish Hall lights,

to judge who had delivered the better beating, I was declared

the winner, though, always a little smarter than poor Ricky,

I understood by how much I had lost.

Benevento’s poem “After Jumper Died” shares the agony of losing a beloved pet, in this case, the family’s collie.

and he was already in fairly full rigor

before we found him, lying stiff in the dank basement

where he slept his final sleep,

I helped my father carry him out

to the trunk of our light green Dodge Dart,

so Dad could drive our dead dog to the ASPCA

office and dispose of Jumper’s seven plus years

as our fairly faithful collie, before disposing

of me at high school baseball practice on a Saturday

morning of a cold March in Queens.

“After The Neighborhood Started to Change” describes how he awkwardly made new friends among the newcomers.

And so I ranged puberty crushed over Puerto Rican

Zoraida, Sylvia, Creole Hallene, instead of blue-eyed

Beths, Marilyns or Margarets. I the only white

in a black singing group, the only Caucasian in the house

of hundreds at the occasional Baptist church or back-

to-some-black-part of Brooklyn gig. I the only blanco

messing with merengue at some salsa-only set,

way out of rhythm but learning the words mejor

y mejor, until the time when the older white folks

couldn’t pick me out of the line-up of minority

teens they feared being mugged by, until all the white

kids still left thought I was at least a little weird, until the new arriving brothers and hermanas were all left wondering

what this honky thought he was doing hanging with their people,

until I grew up and found myself stuck in the small town Midwest,

where everything is mostly all white again, even me.

Celibacy

Benevento’s novel, “The Odd Squad,” takes place in 1971 against the backdrop of the ethnically evolving Richmond Hill. An Italian-American teen makes new friends — one black, the other Puerto Rican — amid racial tension that flowed from the 1960s into the next decade. Meanwhile, like Benevento’s real-life brother, Frank, older kids are away, fighting in Vietnam.

The main character, like his author, attends Cathedral Prep.

After graduating there in 1973, Benevento earned his bachelor’s degree from New York University, his master’s from Ohio State, and his Ph.D. from Michigan State.

He has taught for nearly 40 years at Truman State. With his wife Carol, a kindergarten teacher, he has four children: Maria, 28; Joseph, 26; Claire, 22; and Margaret, 14.

Benevento said his conversations with a priest at Cathedral Prep helped him decide the priesthood wasn’t for him, especially the vows of celibacy.

His poem, “After Zoraida Martínez Saved Me from Divine Word Seminary,” includes these verses about how his priestly plans were disrupted by a family moving into the neighborhood with three daughters. The youngest, Zoraida, caught his eye.

… her topaz eyes

favored me. First she sent pebbles my direction

which only my best friend José interpreted as a sign, next

she confessed to my little brother who it was

she had chosen, so that even I could not forestall

the necessary revelation, our hand-holding sending

golden, electric shocks through me like nothing

praying had ever produced, taking me away from my Divine

Word pretension to admitting my weakness, like a budding

cherry blossom admits the sun, knowing all my poetry would come

from then on as a way to be always recalling that miracle.

‘It’s Still Evolving’

Benevento’s Catholic school education and his lifelong faith also brought more material for fiction.

“The Monsignor’s Wife” is the first book in a trilogy about a fictional priest assigned to St. Teresa of Avila Parish. He challenges Church authority and struggles with celibacy while trying to solve a murder.

“He’s a hypocrite,” Benevento said. “He’s having an affair, living a double life, and it eventually gets him in a lot of trouble.”

Celibacy is also a theme in “My Perfect Wife, Her Perfect Son.” It holds to the Catholic belief that Joseph remained chaste because of the perpetual virginity of Mary.

He explained, “As someone who thought of being a priest and didn’t do it because I couldn’t handle celibacy, and as someone who then wrote a novel about a monsignor who couldn’t handle celibacy, the idea of how St. Joseph managed it in a marriage really fascinated me.”

Benevento confirms there have been times that he has questioned the faith instilled in him by his parents, but he always returns to it.

“It’s still evolving, even as old as I am,” he said. “With Catholicism, I don’t try to be an apologist because it’s not like we never made mistakes. There are so many things we haven’t done right, going back to the Inquisition.

“But it seems to me that of all the Christian faiths, the Catholic faith is the most open to reconciliation. It is the most open to believing that people who are good and loving will find their way to heaven.

“If the faith is there, it can survive questioning. It can survive even some criticism.”

Great article! I know Joe, and have enjoyed and admired both his prose and his poetry for many years. I hope this piece leads to more readers discovering this wonderful author.

I also went to St. Teresa of Avila and graduated in 1964. I loved my time there. I have read Joe’s books and look forward to reading more. I truly enjoyed this article, it brought back such wonderful

memories.

Great article. Brought me back to my days at St. Teresa

Powerful! Very exciting for me, as Joe shared his family with me. I feel privileged ❤️