RIVERDALE — Kevin Horbatiuk, a Manhattan lawyer and lifelong Catholic, loves God and local history. He’s also fond of oysters, and not just to eat.

When not representing clients, Horbatiuk paddles his kayak through the riverine environs of Manhattan Island, New York Harbor, and the Long Island Sound, volunteering with two oyster restoration groups.

For the Billion Oyster Project (BOP), Horbatiuk is a designated “ambassador” who conducts public outreach, lecturing on oyster restoration efforts.

His talks include New York City’s rich history with this local species of mollusks, including the story of Thomas Downing, the “Oyster King.” This 19th century African American “freeman” became one of the city’s wealthiest restaurateurs with his world-famous oyster house.

RELATED: How a Son of Former Slaves Became the Rockefeller of New York City’s Oyster Restaurants

For the City Island Oyster Reef (CIOR), Horbatiuk is an active volunteer on the water, monitoring the health and growth of the oysters around City Island at the western end of Long Island Sound.

“Over time I have realized that a combination of Franciscan reverence for all of creation and an Ignatian call to active service have been propelling my environmental activism,” Horbatiuk said.

‘Praise be to You’

That Franciscan sentiment is shared by Pope Francis, who chose his papal name in honor of St. Francis of Assisi, the 13th century saint who wrote the poetic prayer “Canticle of the Sun.”

In it, St. Francis praises God the Father for creating the world and all of its creatures.

From that prayer, Pope Francis, who died April 21, borrowed the phrase “Laudato si’ ” (Praise be to You) for the title of his 2015 encyclical letter on the environment.

The full title is “Laudato sí’: On Care for Our Common Home.” The letter’s proponents will celebrate the 10th anniversary of its publication on May 24.

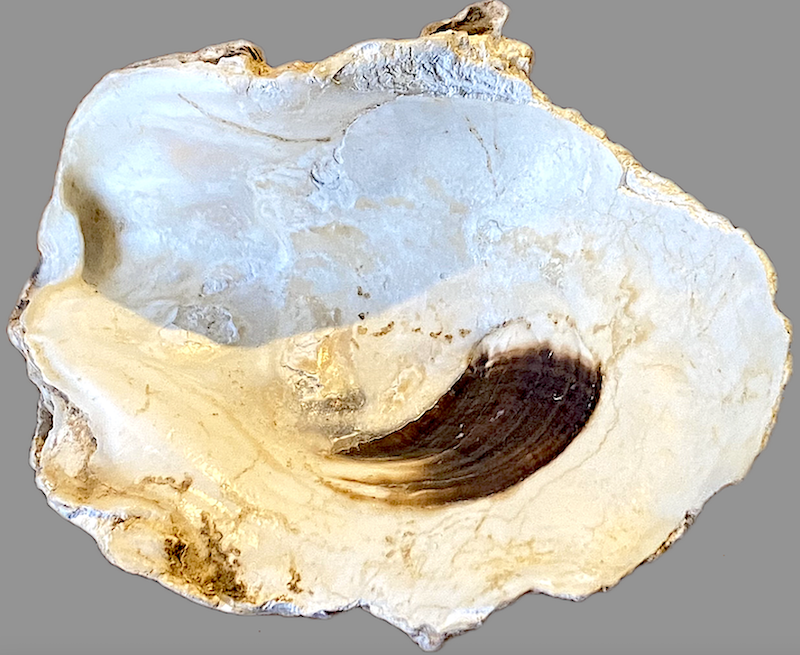

Over the past decade, “Laudato sí’ ” has become famous for urging swift actions to combat climate change and to value every living creature. To that end, the humble oyster could possibly serve as a “poster child” for the movement — with Horbatiuk serving as one of its most ardent champions.

Summer Ritual

Horbatiuk grew up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His mother’s parents were from Poland and his father’s family was Ukrainian. The Fordham University educated lawyer recalled how his dad delighted in exploring different cuisines, including oysters.

“I remember going to restaurants with him and having oysters, and steamers, and different types of clams at a young age,” Horbatiuk said. “Then it became part of the summer ritual.

“We’d go to Long Beach on Long Island, and then we’d stop at Peter’s Clam Bar and get some clams and oysters. It was always a part of what I associated with growing up.”

Concurrently, he developed a deep love of New York City’s past, and earned his undergraduate degree in history, summa cum laude, also from Fordham.

Oyster Beds’ Bounty

Horbatiuk became enthralled with the local history of oysters while kayaking.

“I’ve been paddling in the Hudson River for maybe 15 years now,” he said. “Once you care about the river, and it’s a big part of your recreational life, you just want to get involved.”

Next, Horbatiuk attended a presentation by the BOP at the New York Historical Society, which inspired him to read Mark Kurlansky’s 2007 book, “The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell.” Through it, he learned that when Dutch colonists arrived in Manhattan in the early 1600s, they found the first inhabitants, the Lenape, thriving on the bounty of the area’s abundant oyster beds.

According to Kurlansky, biologists have estimated that these beds were found in the Hudson River estuary, along the shores of Brooklyn and Queens, in Jamaica Bay, in the East River, and “all shores of Manhattan.”

Kurlansky wrote that earlier Dutch colonists “called Ellis Island and Liberty Little Oyster Island and Great Oyster Island because of the sprawling natural oyster beds that surrounded them.”

“I loved Mark Kurlansky’s book, and I found that people were so unaware of the fact that, once upon a time, this was really the ‘Big Oyster, ’ ” Horbatiuk said. “That set me on a path.”

He subsequently joined BOP and CIOR.

Fixing a Tragic Turn

The mollusks’ historic timeline took a tragic turn in the early 1900s when oyster populations collapsed. According to information from the BOP, destructive pollution poured into the mollusks’ habitat — a consequence of human populations growing rapidly on Manhattan and Long Islands.

But humanity would take steps in the 21st century to revive New York oysters. BOP was founded in 2014 to do just that. It helped form the CIOR five years later.

Together, the groups aim to educate the public and implement projects to foster habitat growth for oysters. BOP’s goal is to see a billion oysters in local waters by 2035.

Horbatiuk noted that since 2015, the BOP has collected more than 2.8 million pounds of oyster shells from local area restaurants, which they then return to the local waters for young oysters, called spat, to grab onto and thrive.

As of last year, the groups recorded 150 million oyster larvae restored across 20 acres of New York Harbor.

Whales, Dolphins, Sea Horses

Healthy oyster populations bring three benefits, Horbatiuk said.

First, he explained, a single adult oyster is a “filter feeder” capable of cleaning 50 gallons of water per day. This, in turn, spurs improved habitat for other species now spotted in or near the harbor.

“The biodiversity on the large side are the whales, the dolphins, and the harbor seals,” Horbatiuk said. “And you’re actually finding sea horses and some of these other quasi-exotic little fishes that you would think you’d see in a private aquarium.

“But here you are finding them in the waters off of Brooklyn and Queens.”

RELATED: Rash of Humpback Whale Deaths

Third, oysters can form natural reefs that can block the force of a storm surge, he said.

“The structures are porous,” Horbatiuk explained, “and that’s very important because they can break down the strength of incoming waves during incidents like Superstorm Sandy.”

All Connected

Despite all of these human efforts, Horbatiuk believes the work still needs help from God. He described how he regularly brought his golden retrievers to be blessed at the annual Feast of St. Francis and the Blessing of the Animals at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of New York.

Last year, however, with help from CIOR friends, he brought an aquarium filled with oysters from the Long Island Sound, joining a procession of canines, cats, cattle, and camels.

“I believe very much in the sort of Franciscan view of caring for all creation,” Horbatiuk said. “And you know what the pope said — that when the earth cries, it’s also the people who are crying.

“It’s just all connected.”