By Renée Roden

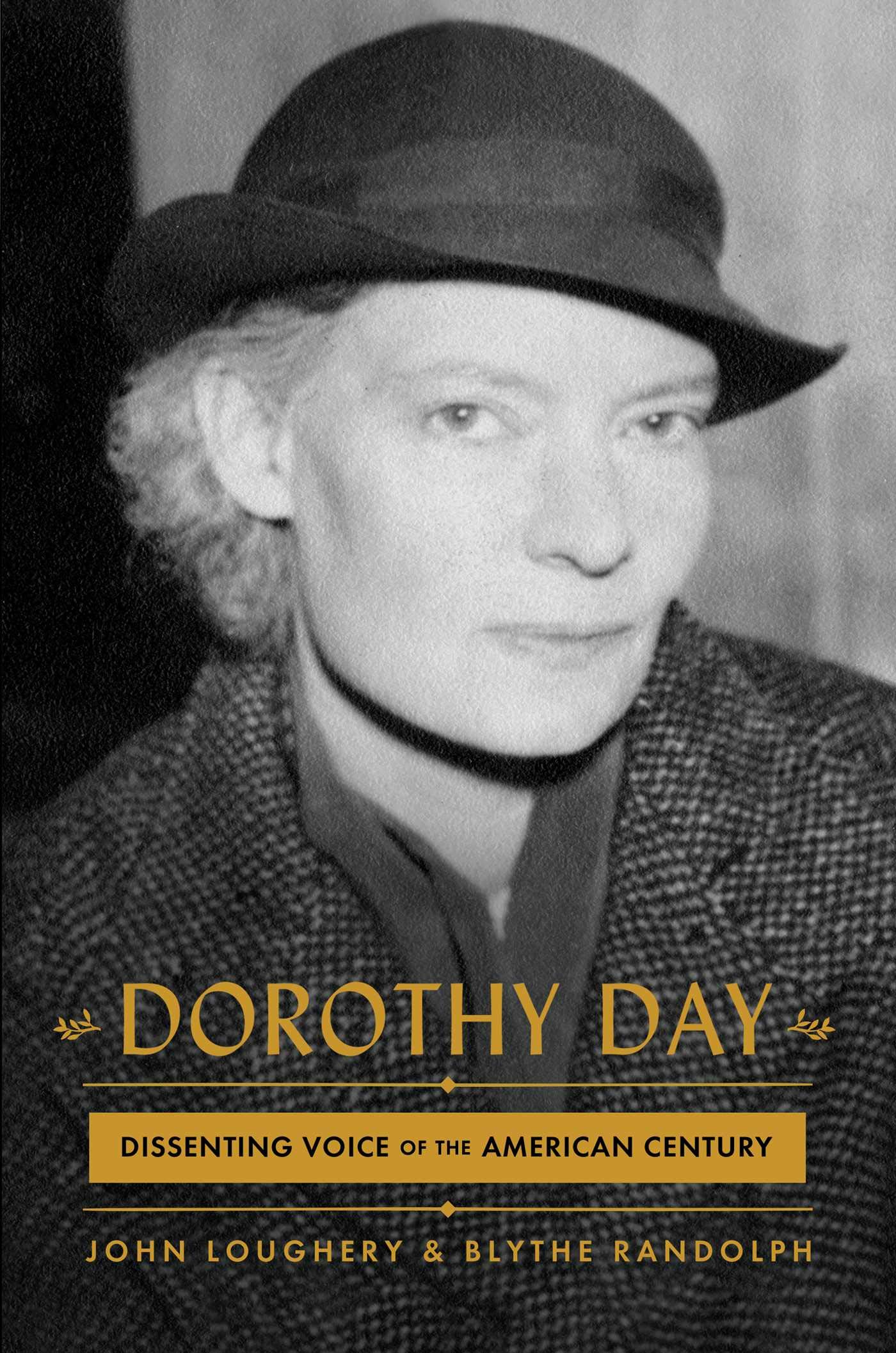

MANHATTAN — John Loughery and Blythe Randolph’s new biography Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century is a fantastic primer on this seminal Catholic fi gure of the twentieth century.

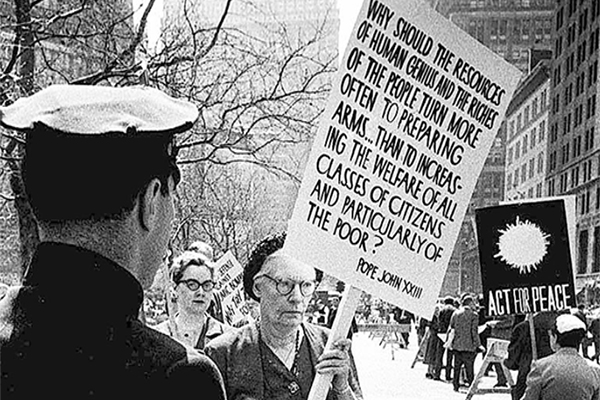

Loughery and Randolph portray Day not so much as a Catholic icon but as a lost voice from the dissenting faction of the American political and literary tradition who paved the way for the resistance and civil rights movements of the 1960s, but whose anti-capitalist and pacifist efforts made them unpopular, marginalized figures in the first half of the century.

There are many excellent biographies of Day already in print, and her journals, letters, and writings detail her life from her perspective. But Loughery and Randolph’s work does an excellent job of explicating Dorothy Day’s Catholicism and religiosity to readers who have never heard of the Catholic Worker and may never have set foot inside a Catholic Church.

Dorothy Day is a complex figure, baffling even to her biographers. Her unabashed socialism, pacificism, and radical nonviolence stand as a challenge to the United States’ status quo. Along with her impressive progressive credentials, Day cherished an orthodox Catholic faith.

Her Catholic orthodoxy often stands in tension with the orthodoxies of other ideologies, particularly her Communist party friends, the anarchist thinkers with whom she corresponded and courted, and the contemporary neoliberal orthodoxies of 21st century secular America.

In Loughery and Randolph’s rendering, Day appears as a true free-thinker who found her freedom in the community: the communion of saints and communion with Christ in the poor.

As a biography, particular worldviews and normative assumptions of the authors seem pretty transparent. The reader will certainly meet Dorothy filtered through their assessment of her faith and her activism.

But this is not entirely a negative point.

As Day herself once wrote: “to write is to give yourself away.” To be a public figure is an act of love, making yourself available to others to turn into whatever they wish yo to be: communist, activist, abbess, radical, or saint. A saint will always have many faces. Loughery’s and Randolph’s new book is certainly not an extensive biography nor an authoritative one, nor does it claim to be.

The authors seek to introduce this important American to those who may have never heard her name until it was mentioned by Pope Francis in his 2015 address to Congress, when he named Day as one of four Americans who truly embody the values for which this country strives.

I encourage readers to pick up this brief overview of Dorothy Day’s beautiful and prophetic life, which will hopefully inspire readers to learn more about this remarkable revolutionary of love in American Catholicism.