Anyone who has read the previous four columns in which I have commented on David Brooks’ “The Second Mountain” knows how much I like this book. I believe the book, which is informative, provocative and inspiring, is a wonderful gift that Brooks has made available to readers. I am hoping it is read by many.

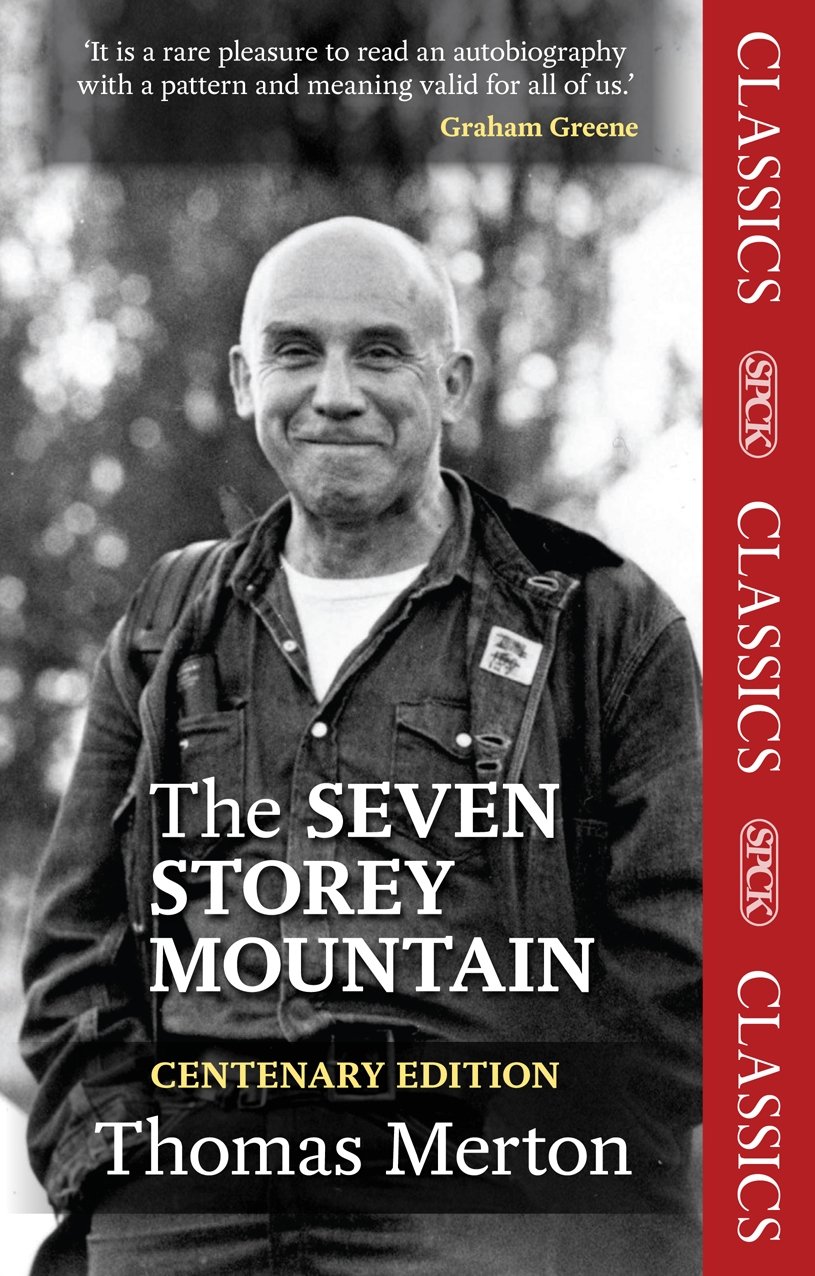

As I finish this series of columns, I have been trying to recall the last book I read in which the author so openly and honestly discussed his own journey of faith. The first book that came to mind was Thomas Merton’s “The Seven Storey Mountain.”

In all the philosophy courses that I teach at St. John’s University, I devote the first class to a discussion of mystery, and I hope that when students reflect on mystery, they will experience awe and wonder. I confess to the students that I know that it is not easy for an undergraduate, who is busy with exams and term papers, to experience awe and wonder, confronting in a philosophy course mysteries such as freedom, love, death and God, but I tell them that I hope that is what their experience will be.

I stress that what we do in philosophy class is explore some of the most important truths human beings have discovered. Borrowing an insight from Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Brooks writes

the following: “Rabbi Heschel says that awe is not an emotion; it is a way of understanding. ‘Awe is itself an act of insight into a meaning greater than ourselves.’ And I find that these days I can’t see people except as ensouled creatures. I can’t do my job as a journalist unless I start with the premise that all people I write about have souls, and all the people I meet do, too. Events don’t make sense without this fact. Behavior can’t be explained unless you see people as yearning souls, hungry or full depending on the year, hour, or day.” (p. 232)

I add to Brooks’ comment that nothing I do as a priest, from celebrating Mass to writing a column, would make any sense if human persons do not have souls. In recent years the idea that all persons, in union with a loving God, are writing the stories of their lives by their free actions has become central to my view of human existence.

No one is ever alone. As Pope Francis has insisted, God is part of everyone’s life. I also believe that there is no such reality as an insignificant human person, no such reality as an unimportant person. Every person, from a world leader to someone in a nursing home suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, has a significant role to play.

I don’t know of any columnist in any secular newspaper who writes essays similar to those Brooks frequently writes in the New York Times. He often writes about philosophical and religious issues, issues that interest him deeply. Friends of mine and I, who read Brooks regularly, have often commented on his his life. I find Brooks’ honesty especially attractive.

His background is the Jewish faith, but he finds Christianity very appealing. He seems to be on a border between the two faiths. Reflecting on the power, beauty and enormous appeal of Jesus, Brooks writes the following: “Which brings me to the crucial question: Do I believe in the resurrection of Jesus Christ? Do I believe his body was gone from the tomb three days after the crucifixion? The simple brutally honest answer is, It comes and goes. The border stalker in me is still strong.” (p. 246)

I am encouraging friends to read “The Second Mountain” and to reflect on Brooks’ marvelous insights. The book could be wonderful for a discussion group. I am hoping that a priest discussion group of which I am a member will choose to discuss the book. The book is so good that even disagreeing with some of Brooks’ observations might be a beneficial experience.

The following is a summary statement Brooks makes at the end of the section in his book on philosophy and faith: “Throughout this book I’ve been talking about commitments as a series of promises we make to the world. But consider the possibility that a creature of infinite love has made a promise to us. Consider the possibility that we are the ones committed to, the objects of an infinite commitment, and that the commitment is to redeem us and bring us home. That is why religion is hope. I am a wandering Jew and a very confused Christian, but how quick is my pace, how open are my possibilities, and how vast are my hopes.” (p. 262)

It seems fitting to me to end this series of columns on Brooks’ book with that beautiful statement.

Father Lauder presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, Tuesdays at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.